Whenever I visit Paris, I love to spend time going through bookstores, looking for interesting French books for my library. On my last trip, I went to the Librarie Le Phénix, my favorite bookstore for works on Asia and Asian Americans. While browsing the shelves, I came across a paperback with the delightful title Chroniques d’un trimardeur japonais en Amérique. [Chronicles of a Japanese Vagabond in America]. The author was listed as Tani Jôji. I had never heard of either the author or the work in question.

I bought a copy of the book, and as I started reading the text (more about that later), I became increasingly curious to know more about “Tani Jôji.” With help from translator Gérald Peloux’s afterword and some further researches, I was able to learn something of the life and work of the author.

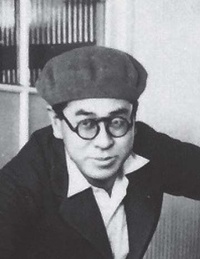

He was born Hasegawa Kaitarō (AKA Kaetaro Hasegawa or Umetaro Hasegawa) on Sado Island in Japan in January 1900, and grew up in the city of Hakodate in Hokkaido. His father was Hasegawa Seimin, president of the Hakodate Shimbun newspaper. His three younger brothers, notably the well-known novelist Hasegawa Shiro, would all become writers.

After studying for a time at Meiji University, Hasegawa went to the United States in 1920 and enrolled at Oberlin College, reportedly worked as a dishwasher and circus boy to earn his tuition. Hasegawa ultimately dropped out of school, and lived a vagabond life, travelling first around the Midwest and then elsewhere. In the July 24, 1921 edition of New York Herald is a “situations wanted” advertisement by “K. Hasegawa” that read “Japanese butler or general houseworker desires position in small family; city or country; honest, reliable; best references.”

In early 1924, Hasegawa returned to Japan, making his way back by means of work on cargo vessels. Apparently he intended to stay for only a short time, and then return to the United States. However, after the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act was enacted, barring all entry into America by Japanese and other Asians, he was refused a visa. Thus, Hasegawa settled in Japan, as a kind of exile in his native land, and soon after married a Japanese woman.

He soon joined a group of writers working for the magazine Shinseinen [New Youth]. While the magazine was known for featuring detective fiction, most famously by the mystery writer Edogawa Rampo, it would also become an outlet for popular modernist literature. Under the pen name Maki Itsuma, Hasegawa began publishing mystery stories, and also translated the work of foreign mystery writers.

Meanwhile, using the pen name Tani Jôji, Hasegawa began publishing his tales about his days in America, in a series of writings he called merikan jappu (’Merican Jap). The series, set in the United States during the Jazz Age, portrayed in idiosyncratic style the author’s experience in an American demimonde of automats, dance halls, and speakeasies.

In 1929, as Tani Jôji, he published a book of American stories, Tekisasu Mushuku [Texas Homeless Wanderer]. Soon after, he published another collection of tales, Modan Dekameron [A Modern Decameron]. In 1928, with sponsorship from the magazine Chūō Kōron [Central Review] he visited 14 European countries with his wife, and produced a series of essays and stories which he sent back from each port of call. On his return he produced Odoru chiheisen [Dancing Horizon], a collection of these pieces. Meanwhile, he published a set of Japanese translations of Western novels, including Upton Sinclair’s They Call me Carpenter and Lion Feuchtwanger’s Jud Süss (it is unclear whether he worked from the German-language original or the English version, Power).

The popularity of the Tani Jôji stories opened the doors for Hasegawa to publish in more mainstream newspapers and magazines, and inspired him to branch into other areas of writing. In the next years, he produced modernist short stories, historical novels, family melodramas, humorous stories, translations, and essays. Under his pen name Itsuma Maki, he published Kono Taiyo [This Sun], Chijō no Seiza [Constellation Earth], and Atarashiki Ten [New Heaven].

In addition, he took up the pen name Hayashi Fubo, under which he published samurai tales set in the Edo period, such as Shimpan Ooka Seidan (1928). His most notable historical work as Hayashi Fubo featured the character Tange Sazen, a master swordsman with only one eye and one arm.

Within a few years, Hasegawa published so many novels, stories, translations and essays that he was dubbed “the literary monster” by Japanese critics. His novels were adapted into films. 1928 saw the release of the first of a number of Tange Sazen samurai films by different directors, based on the Hayashi Fubo books featuring that character. In 1933, director Abe Yutaka filmed an adaptation of Atarashiki Ten. Chijō No Seiza, from the Maki Itsuma novel, was filmed as a two-installment picture in 1934 by Nomura Hôtei, with Tanaka Kinuyo in the lead role.

Hasegawa died suddenly of a heart attack—presumably brought on by overwork—in Kamakura on June 29, 1935. He was only 35 years old. At the time of his death, he was at the peak of his fame, and was the most commercially successful writer in Japan. His death brought to a halt the set of popular novels he was in the process of writing, which he published in monthly installments in popular magazines. While serialized novels such as Shin Gankutsuo [New Cave King] and Oyabun Onemuri [Sleeping Boss] remained uncompleted at the time of the author's death, they appeared in book form in later decades.

Even though Hasegawa Kaitarō remained absent from the United States after 1924, his works circulated there. The stories featuring Tange Sazen (originally Ooka Seidan) that he published as Hayashi Fubo were republished in Shin Sekai in 1928, and serialized in Yuta Nippo starting in 1933. Shin Sekai also serialized two of his works as Maki Itsuma in the early 1930s. While curiously, none of Hasegawa’s Tani Jôji stories was ever serialized in the Japanese vernacular press, advertisements for his book of collected stories did appear in both Kashu Mainichi and Nippu Jiji. When Hasegawa died, the Great Northern Daily’s Japanese section reported the news on its front page. (I wish to give thanks to Takako Day for checking the information in this paragraph for me).

Even more impressively, Hasegawa had become sufficiently eminent as a writer that his passing was recorded in the Nisei press, even if none of his works had appeared in English. Kashu Mainichi noted, “Using three different pen names, Itsuma Maki, Joji Tani, and Fubo Hayashi, he contributed to almost all popular magazines in Tokyo, and was one of the most popular and active writers.” The article further stated, “He has been to this country about ten years ago, and was educated in the middle west. The stories about his life in Texas and Arizona, Texas Mushuku is one of his masterpieces.”

Larry Tajiri, writing in Nichi Bei Shimbun, affirmed, “As Itsuma Maki, Hasegawa, who came to the United States in his youth and studied in American schools, wrote modern day stories of Nippon, writing one story which netted him 200,000 yen, the highest sum ever earned by a Japanese writer for one book. As Hayashi, he penned stories of samurai valor. As Joji Tani he wrote American adventure yarns. As Tani he wrote a story of the Texas prairie.” Tajiri asserted that Hasegawa stood “on a level with Kan Kikuchi and Tosan Shimasaki” as Japan’s three most popular writers.

Perhaps the most ardent admirer of Hasegawa among the Americans was James T. Hamada, a Hawaii-based journalist and critic whose novel Don’t Give Up the Ship (1934) was one of the very first pieces of fiction by a Nisei. Upon learning of Hasegawa’s passing, Hamada declared in Nippu Jiji, “To me, he's the best of modem Japanese novelists.” Hamada added that Hasegawa’s death was a tragedy because it signaled the demise of three important authors—never in the history of world literature had there been an author who wrote under so many nom de plumes—and that literary fans in Japan and Hawaii would greatly miss all three writers very much. In a display of his avid reading, Hamada recounted the plot of the serialized novel Kokoro No Hatoba, which he had previously read in magazine installments.

Hamada regretted particularly the loss to the cinema that Hasegawa’s death entailed, given the number of screen adaptations of Hasegawa’s works that had already been produced. “Not all of them, of course, were worthy of that much length. The only one that deserved it was Tange Sazen, because samurai films are best when they're that long. Short ones are often trash. But the mere fact that the stories of Maki and Hayashi have been produced in two installments is testimonial to the importance of the authors.”

One last echo of Hasegawa in America appears in Strawberry Road, Yoshimi Ishikawa’s memoir of his years in the 1960s as a young immigrant from Japan, laboring on his brother’s strawberry farm in rural California. In the book, the narrator describes visiting the house of a Japanese Christian minister and his wife, the first real intellectuals with whom he has come into contact. The young man is impressed by the collection of modern books in their library, with rare editions of works by such authors as Soseki Natsume, Ryunosuke Akutagawa, and Kafu Nagai, and by their conversations about famous authors they had known in Japan.

“I got up and searched the bookcase and before I knew it had picked up two books, Texas Rambling and American Japs on the Go. Perhaps I had a presentiment that I would end up like the people in the books.” His host explains the identity of their author, and his pen names, then adds “I lived with him for a while when he was young and wandering around America. He’s dead now. He was a nice man.” Ishikawa’s deft tip of the hat to his literary forbear and the kinship he feels with the characters in the Tani Jôji stories all point up the continuing relevance of Hasegawa’s literary legacy.

© 2022 Greg Robinson