Before we look at what happened to Toshiyuki after 1959, let's first trace the story of his family. Toshiyuki returned to the United States in 1956, and his parents and younger siblings returned to Los Angeles the following year in 1957. Around this time, the 1952 amendment to the immigration law limited immigration from Japan to 185 people per year, but this limit did not apply to family members of Japanese citizens.

"My father worked in Japan, importing the raw materials for nylon stockings and manufacturing them. He said he wanted to go to a manufacturer of the stocking materials and start his own company there, so he left Los Angeles for South Carolina. But it would be too much to do alone, so he asked me to come with him, and the three of us - my father, my youngest brother and me - drove there. In the town of Ruby, we made stockings to a nearly finished state, and sent them to Japan to sell."

Ruby is located near the state border with North Carolina, and is still a small town with a population of about 350. "Ruby was a really rural town. Most of the population was white, and there were no black people, let alone Asians. My father's company employed several people, but many of them could only write their own names to sign checks, and many of them could not write."

A few months later, the rest of the family in Los Angeles joined us, and the seven of us started living together in Louby for the first time in a long time. "At that time, I was 18 years old and my brother was 19. He told me that I should go to college, so I started going to a university about 50 miles away, but I didn't study that much at university, and I couldn't do judo here, so I asked my father, 'I want to do judo, so can I go to Los Angeles?' He said, 'If you say so, it's fine,' so I returned to Los Angeles after about six months.' And Toshiyuki returned to the Hollywood dojo again in 1958, and he devoted himself to judo while working part-time at a small Japanese-owned supermarket nearby called Fujiya Market.

Now, let's go back to 1959. That year, the US Air Force team participated in the National Championships held in San Jose, and the coach approached Toshiyuki. "Kiyono, how old are you?" the coach asked, and Toshiyuki replied, "I'm 19, why?" Toshiyuki then asked again, "Are you going to school?" When Toshiyuki said, "I'm going to City College," he continued with the question, "How are your grades?" "I thought that was a strange question to ask, but I replied, 'I've only been in America for less than three years, and I don't speak English very well, so my grades aren't good. I think I'm getting about a C out of ABCD.' Then he said, 'Well, you're going to be drafted.' In those days, there was a conscription system, and if you were drafted, you had to serve in the Army for two years." The Air Force coach then continued, "Why don't you join the Air Force?"

However, if he joined the Air Force, he would have to serve for at least four years. Toshiyuki replied that he did not want to spend that much time in the military, but the director persuaded him, saying, "The Air Force is looking for a teacher to teach self-defense to pilots. If you join the Air Force, it will be four years, but in the meantime, we will send you to Japan to study at the Kodokan." The Air Force had a contract with the Kodokan, and each year they sent several people to study self-defense, and then when they returned home they taught other soldiers. "I thought it would be great if I could go to Japan."

After joining the Air Force, Toshiyuki first had to undergo three months of basic training in Texas. Toshiyuki says that there was some trouble during this basic training.

"One time, another soldier in training called me a 'Jap'. I got annoyed and asked him, 'What did you just say?' He replied, 'What's wrong with calling a Jap a Jap?' I said, 'I'm American. Not a Jap,' and he grabbed my neck or something. Since I do judo, I threw the big guy right away. He was shocked and said, 'Sorry, sorry.' There aren't many Japanese in the Air Force, so things like that did happen."

After that, Toshiyuki went to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona. About six months later, he received orders to go to Japan. "A total of 14 or 15 people from other air bases flew from Travis City Air Force Base to Fuchu Air Base on the outskirts of Tokyo."

Over the next three months, nearly 20 members of the Air Force stayed overnight at the Kodokan to learn aikido, judo, karate, and arrest techniques. "Experts came and taught us every day, Monday through Friday. The only people in the Air Force who could speak Japanese were myself and one other person, Mr. Miyazaki, who happened to practice judo and was stationed at Fuchu Base. The two of us acted as interpreters and taught us. He had also returned to the United States."

After three months of intensive study and returning to Japan, he taught self-defense to pilots. "Because if war breaks out and you get shot down somewhere, it's better to be able to protect yourself." Toshiyuki was the only one teaching self-defense at the Davis-Monthan base. Of course, he had no one to practice judo with. "So, I heard that there was someone practicing judo in Tucson, so I went there, and found that someone originally from Los Angeles was teaching there and knew my name. After learning judo at the Seinan Dojo, he opened his own dojo in Tucson, and I often went to practice at the Seinan Dojo."

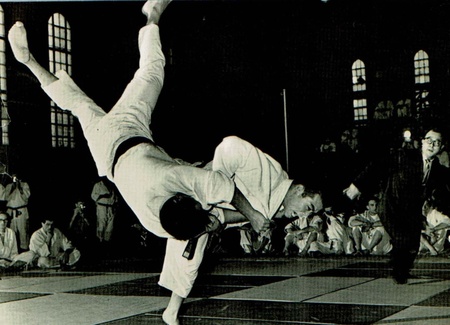

He trained and taught at the Tucson dojo for about four years, and participated in judo tournaments all over the U.S. At the tournament at the Air Force base, after four weight classes, there was a grand champion match in which the four winners of all weight classes competed. Toshiyuki, who competed in the 70kg class, continued to win that match during his five years in the Air Force.

When asked the secret of his strength, Toshiyuki replied, "I did a lot of judo. Throwing is fun. I practice more than the average person, and even when I'm alone at home, I practice on the wall." In many cases, it was the jump hip or inner thigh throw that decided the match.

"Everyone knows my special techniques, so I am invited to judo clinics to teach the jumping hip technique, but it is a technique that cannot be performed without flexibility."

His fingers and toes are curled from years of gripping the thick judogi and slamming in and out of it, and his passion for the sport is radiating from them.

Continued >>

© 2022 Masako Miki