As readers of this column know, I have done a great deal of research in recent years on the panoply of Asian American performers who worked in Hollywood in the generation before World War II. Theirs was not a simple life. Hollywood studios made frequent use of white actors in yellowface to portray Asians (many of these portrayals now seem cringeworthy to a current-day audience). Even such roles as ethnic Asian performers were given to play, whether servants, menial laborers, or sensual exotics, often carried a heavy load of stereotyping and condescension. Worse, their parts were often small, sometimes uncredited, and in any case greeted with scant critical attention. An interesting case study of the travails of Asian American actors in 1930s Hollywood is that of two performing siblings, Otto Yamaoka (AKA Otto Hahn) and his sister Iris.

Otto and Iris Yamaoka were born in Seattle, to Otohiko and Jho Josephine Yamaoka. (I have previously told some of Otohiko Yamaoka’s story in my Discover Nikkei article on Otto and Iris’s oldest brother, attorney George Yamaoka). Otohiko, born in Japan, had been in his youth a leader of the Liberal Party and member of the Diet, but had then been convicted of involvement in the “Kahasan incident,” a conspiracy to assassinate government officials, and had spent ten years in prison.

Following his release, he emigrated to the United States, where he worked as a labor contractor and director of the Oriental Trading Company. At the time of his death in 1924 he was hailed for his work as a Japanese community leader, especially for helping sponsor Takao Ozawa’s notable legal challenge to denial of naturalization rights, and thereby alien land legislation.

Otto Han Yamaoka was born in Seattle on April 25, 1904. According to later press reports, he attended Lincoln High School, where he starred as an athlete. In addition to playing baseball and basketball, he starred as a halfback for Lincoln's football team, the Railsplitters, and was ultimately named to the Seattle All-City Squad. However, a surviving photo of Yamaoka from a Broadway High School yearbook suggests he studied there.

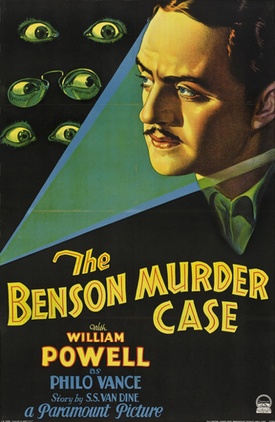

Sometime after completing his schooling, Otto moved to San Diego, and from there on to Hollywood, where initially he worked as a salesman for a costume company. He received notice for playing the part of Sam, the houseboy of detective Philo Vance, in the 1930 talking picture, The Benson Murder Case, starring William Powell. His first real break, however, came the next year when he was cast in The Black Camel, which starred Warner Oland as Chinese detective Charlie Chan. Otto Yamaoka played Chan’s Japanese assistant, Kashimo. Philip K. Scheuer, writing in the Los Angeles Times, found Yamaoka’s characterization “amusingly overzealous.” Winifred Aydelotte wrote in the Los Angeles newspaper The Record that Yamaoka “has one of the best comedy routines in the film.” Nisei author James Hamada lamented in the Nippu Jiji, however, that Yamaoka’s performance as the “harebrained and overzealous assistant” was overly silly, even for purposes of comic relief.

Otto Yamaoka soon thereafter was cast in William Wellman’s film The Hatchet Man, which featured Edward G. Robinson and Loretta Young in yellowface. Otto Yamaoka plays Chung Ho, the leader of a clan group in the midst of a Tong war in San Francisco. It was to be his sole purely dramatic role during the decade.

In 1933, Yamaoka played several parts. He had a featured role as a Japanese chauffeur in Racing Strain, an independently-produced film starring Wallace Reid, Jr. Larry Tajiri noted in Nichi Bei Shimbun that Yamaoka “had one of the best bits which has fallen to a Japanese player of recent date. His role was pure comedy with intriguing situations.” He also played various bit parts. In World Gone Mad, he played a stereotyped butler part. Soon after, he had a role in the Columbia film Before Midnight. In Limehouse Blues (1934), he was cast as a Chinese waiter on a boat. He had an uncredited role as a servant in Katharine Hepburn’s 1934 vehicle Morning Glory.

In 1934, Yamaoka appeared in a small but important role in the comic film We’re Rich Again. He plays Fujii, a Japanese servant with broken English who is magically able to buy an entire dinner’s worth of vegetables for 25 cents, and who pulls the leg of his employer (played by Billie Burke) by telling her that the Depression has hit Japan so hard that silk worms are producing only cotton.

The following year, he played a featured role in King Vidor’s film Wedding Night, as Taka, Gary Cooper's valet. Larry Tajiri identified in Nichi Bei Shimbun two good bits performed by Yamaoka. First, as he warms his hands over a kitchen stovetop at his employer’s Connecticut country house on a cold morning, he utters "Samui, samui" (which Tajiri marveled was one of the few times Japanese words were heard on the U.S. screen at that time). Another powerful moment is of Taka running away from the house in the dead of winter. According to one source, TIME magazine listed the scene in which Taka tiptoes through the snow as one of the best in the picture.

1936 was a similarly rich year for Otto Yamaoka. He appeared that year in Petticoat Fever, a love story adapted from a successful Broadway play, set in Labrador, in the then-independent nation of Newfoundland. Yamaoka plays Kimo, an Inuit [then known among whites as Eskimo] who was manservant of the lead character, played by Robert Montgomery. (Interestingly, Yamaoka had prepared for the role the previous year by playing the part of Kimo on stage during the Los Angeles run of the original play, opposite Dennis King).

Barbara Miller, writing in the Los Angeles Times, praised Yamaoka’s screen performance as “exceptionally amusing,” Critic Kate Cameron added in the Daily News that the role was “delightfully played,” while in the Washington Post, Nelson B. Bell singled him out among the cast for doing “rather the best job of the lot”. Mildred Martin, writing in the Philadelphia Inquirer, compared Yamaoka’s comic portrayal of the “merry-faced [Kimo]…who has good ideas and carries them out” to the silent comedian Harpo Marx.

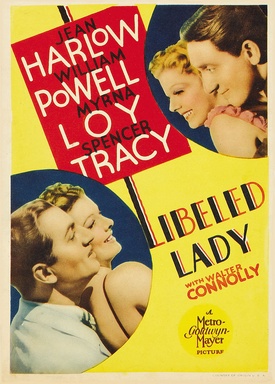

In addition to these more substantial parts, Otto Yamaoka appeared in a selection of bit parts in this period. He played a Japanese chauffeur in Columbia's Death Flies East (1935). In the 1936 musical Rhythm on the Range, he played a Chinese houseboy. He also appeared as Ching, Spencer Tracy's valet, in Libeled Lady (1936). Shortly afterward, Yamaoka appeared in the film Criminal Lawyer, starring Lee Tracy. As Mitsu, a Japanese houseboy with a sense of humor, Yamaoka lent a comical note to the picture, and as in Wedding Night, managed to squeeze a few words of Japanese into the dialogue.

Perhaps his last important role came in the RKO film Night Waitress, a melodrama set on the San Francisco Waterfront. Otto Yamaoka played Fong, a Chinese boatman and cook, the trusted guard of a sea schooner under the command of Captain Rhodes, played by Gordon Jones. Yamaoka may have owed his life to his costar.

According to a publicity story circulated at the time, the cast and crew filmed the production on a 45-foot sailing boat anchored off Catalina Island. One day, when he was not needed for a scene, Yamaoka went fishing off the bow of the boat. He hooked a tuna, but when the boat gave a sudden roll, he lost his footing and plunged overboard. Yamaoka tried to hang onto his rod and was dragged under water. Gordon Jones (a onetime Pacific Coast star athlete) dived after Yamaoka and not only held him up until a life buoy was thrown to him, but salvaged the fishing tackle and landed the tuna.

By this time, Yamaoka’s career had started to slow, though he appeared in bit parts in Song of the City, as the valet to an Italian family, and the Western film Trouble in Sundown (where his character bears the delicious name of Foo Yung). He turned his attention instead to business activities.

In May 1936, he opened an importing company with the title of K. Yoshimura and Co. There are different stories about his business interests. According to one story, Otto Yamaoka ran a gift shop in the Hotel Roosevelt. According to another, he became operator of a costume shop in Hollywood. What is certain is that around the same time, he married a non-Japanese wife in Mexico. The marriage would soon fall apart.

In 1939, Mrs. Irene Yamaoka sued for divorce, charging that Otto Yamaoka had physically abused her and acted cruelly. In response, Otto Yamaoka launched a pair of "in alienation of affections" suits, in which he accused two other ethic Japanese of courting his wife.

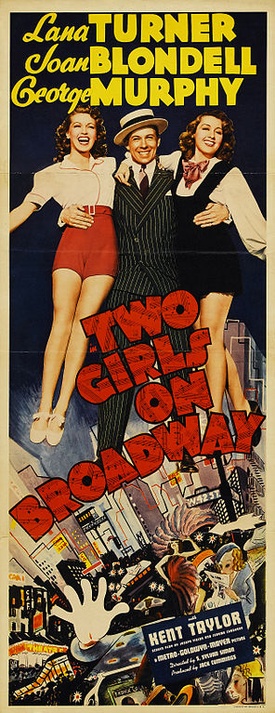

Following the divorce, Yamaoka returned to the screen once more, as Ito the Japanese valet, in MGM’s Two Girls on Broadway (1940), starring Lana Turner. Though the character was clearly Japanese, he was credited in the film as Otto Hahn (Hahn being the name of his attorney, as well as a version of his middle name Han).

The rest of Oto Yamaoka’s life is somewhat more obscure. After his divorce, he married a second time, to a Japanese American woman. The couple, along with other family members, were removed under Executive Order 9066 and confined, first in Santa Anita, then in the Heart Mountain camp.

In August 1943, Otto Yamaoka joined his brother George and other family members in New York. There he opened the firm of Yamaoka & Co. Importers and Exporters., which was most notable for distributing Japanese films to the US market.

Otto Yamaoka did have a final turn before the cameras. In 1962, he appeared in an episode of the TV police series The Naked City (the episode starred William Shatner, who would go on to play the lead in Star Trek, opposite Nisei actor George Takei). The episode, entitled “Without Stick or Sword,” featured Yamaoka as a Burmese sailor who comes to New York seeking revenge on the captain of a ship he held responsible for the drowning death of his four brothers.

Otto Yamaoka died in New York in 1967.

© 2022 Greg Robinson