March marks 80 years since the U.S. issued an exclusion order that forced Japanese Americans from their Bainbridge Island homes. Today, Washingtonians look back on that time.

The United States uprooted hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans during World War II. Eight decades later, the scars remain for Washingtonians whose families lived through it.

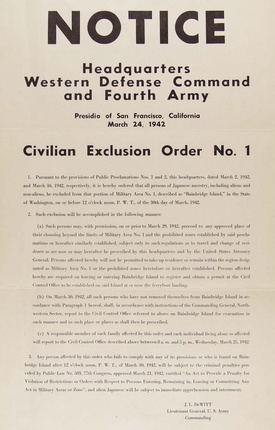

Feb. 19 marked the 80th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which led to the incarceration of Japanese Americans in camps during World War II. The order arrived after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and amid anxieties that Japanese Americans were a threat to the country. One month later, on March 24, 1942, the Army issued the first Civilian Exclusion Order (which the Japanese American Citizens League considers a euphemism for a detention order) for people living on Bainbridge Island.

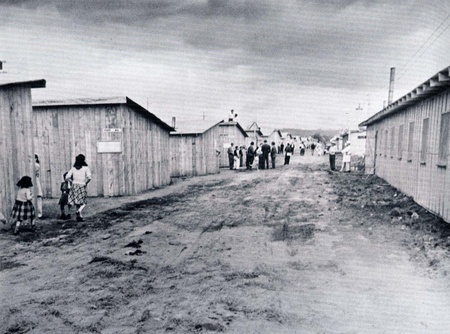

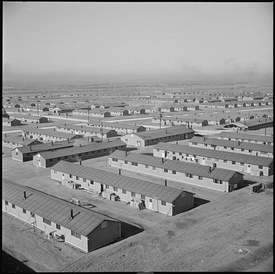

Japanese Americans were sent to assembly centers (again, a euphemism for a temporary detention facility, according to the Japanese American Citizens League) over the subsequent months, like one in Puyallup, occasionally referred to as Camp Harmony. Groups were then sent to 10 camps scattered around the country, including Minidoka in Idaho, where many Washingtonians and their families were incarcerated during the war. Around 120,000 Japanese Americans, mostly U.S. citizens, lived in the camps.

“We were taken from our home in Seattle and moved to Puyallup by the government,” remembered Atsushi Kiuchi, 92, who was in Minidoka for three years and now lives in Washington. “In August 1942 we were shipped by train to Idaho.”

While he lived through Executive Order 9066, Eileen Yamada Lamphere was a product of it.

Lamphere’s parents met in Minidoka and had her a few years after the war ended, raising her in Kent. Lamphere, 72, did not fully understand what the incarceration camps for Japanese Americans were like until she got older.

In separate interviews with Crosscut, the two reflected on the impact of the order, describing a history of shame and a lack of progress since.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

* * * * *

Did your family see incarceration coming or did it take them by surprise?

Atsushi Kiuchi: We knew something was going to happen to us. We didn’t realize it was going to be an incarceration and loss of freedom and all that stuff ‘til probably about February.

The Army decided that we could be saboteurs and adversely affect the nation’s security and defense.

Eileen Yamada Lamphere: I do remember them thinking that their parents would be taken away, because their parents by law could not become citizens.

I think there was always an anticipation that something was going to happen, but it was going to be for the Issei [the first generation — those not born in the U.S.]. So, I think, for the most part being American citizens, that surprised people.

What was it like for those in your family who experienced incarceration? Are there any accounts that stick out?

Kiuchi: You lost all freedom. You had to stay behind the barbed wire fences.

You had people come by in Puyallup, especially. People would drive by and look inside the camp and look inside the barbed wire and point and look and laugh at us.

There was no privacy. There were armed guards walking the sides of the fence.

Lamphere: When they came back from the war, they collectively decided that they were going to be Americans. From the Japanese point of view, going to prison, going to jail, only bad people are imprisoned.

So even though they didn’t understand what was happening, there was that shame. And so you didn’t talk about those shameful parts of your life.

I always knew I was Japanese American. I did not know what that really meant in terms of politics until much later in life. My parents, I would overhear conversations about camp and they never told me a lie, but they let me believe what I thought the camp was like.

And I thought the camp was like a Boy Scout camp, right? Marshmallows and campfire and campers.

They never corrected me.

Did your family ever think about leaving the U.S. once incarceration was over?

Kiuchi: We were too busy trying to make a living.

Some did. The sad part of that is those who wanted to be expatriated, they did go back to Japan. And they found a very, very difficult situation because they were still recovering from the war.

There was equally bad bias or prejudice against those Japanese from America that elected to go back to Japan.

Was there ever consideration on your family’s part post-incarceration to leave the area or the country?

Lamphere: No, on both my father’s side and mother’s side.

I know that one of my father’s brothers, they were released from camp to go to Ontario, Oregon, to help out the farmers there. So they got work releases and after the war they stayed in Ontario.

Ontario, Oregon, was a very unique community. There was already a Japanese community there. and they were not removed. So the Japanese community there supported people coming out of the camps, and so did their business people.

Is there anything you would like to add that you think people don’t understand or that they get wrong?

Kiuchi: The official determination of the cause of all this was, No. 1, racial prejudice. No. 2, wartime hysteria. No. 3, failure of the political leaders of our country.

Now, you take those three things and think about today. What’s been happening the last 25 years and now, even in the corner, some remote corner of the world today, even right now as we’re talking.

Those three issues will unfortunately always be with us. We should have learned something, but we’re not. We’re still making the same mistakes.

Lamphere: I think a lot of the general public thought of it as camp. But they had no idea what these camps were like.

That they were surrounded by barbed wire. That they only had a single light bulb and a potbelly stove. There was no running water. There were no closets. There were no chest of drawers. There were metal cots and for some of them, they had to stuff their own mattresses with straw.

And that’s what’s happening right now. You look at pictures from those detention centers that are down on the border and even up here in Tacoma.

Unless you’re an American, we’re saying that it’s OK for that to happen because they’re not citizens. I just need to let people be aware of what happened and what’s happening now. And is this going to be our legacy?

* * * * *

LIFE AFTER THE WAR

It took decades for the United States to come to terms with its treatment of Japanese Americans. Kiuchi described a culture of hostility and prejudice when people returned to their homes on the West Coast.

People previously living in the camps were given “$25 and a train ticket to wherever they wanted to go,” The New York Times reported. Once they were released from Minidoka, Kiuchi’s family started over in a small farming community in Idaho.

In the years following, he said, incarceration was not necessarily a secret, but it was also not often discussed.

“Even with our parents, we didn’t talk about the fact that we had spent three years basically as prisoners of the United States,” he said. “When I went to enroll in school … I was ashamed to tell that I was in a camp.”

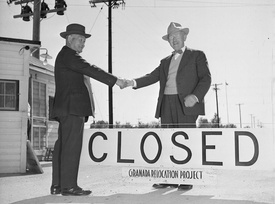

Over the next few decades, the country’s leaders acknowledged the harm to Japanese American families. President Gerald Ford described the issuing of Executive Order 9066 as “a sad day in American history.”

“In this bicentennial year, we are commemorating the anniversary dates of many great events in American history,” he said in a 1976 proclamation. “An honest reckoning, however, must include a recognition of our national mistakes, as well as our national achievements. Learning from our mistakes is not pleasant, but as a great philosopher once admonished, we must do so if we want to avoid repeating them.”

President Ronald Reagan echoed Ford’s sentiment a decade later in 1988 remarks on the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

“Yes, the nation was then at war, struggling for its survival, and it's not for us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes while engaged in that great struggle,” he said. “Yet we must recognize that the internment of Japanese-Americans was just that: a mistake.”

Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act in 1988, which gave a formal apology to people who experienced incarceration, as well as $20,000.

“It didn’t do anything good for my dad,” Kiuchi said.“‘Cause my dad was already dead.”

*This article was originally published in Crosscut on March 8, 2022.

@ 2022 Maleeha Syed / Crosscut