Katsuji Kato as a missionary for Japanese students

The Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions originated in New York in 1886, and the Student Volunteer Band for Foreign Missions on campus of University of Chicago “was composed of members of the International Student Volunteer Movement, organized in 1888.”1 In 1895, the Chicago branch of the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions was housed within the Bible Institute for Home and Foreign Missions of the Chicago Evangelization Society (which later become Moody Bible Institute), located at 80 Institute Place.2

Kato himself was very interested in missionary work, and was especially enthusiastic about using Christian principles to help Japanese students in the U.S. He undertook the position of student secretary for the International Committee of Young Men’s Christian Association's Student Department in July 1913, with a focus on working with Japanese exchange students.3 The International Committee of the YMCA was deeply involved with the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions and employing Kato was a perfect match.

While he appreciated the role that they played in building modern Japan, Kato was not satisfied with the work of American missionaries in Japan. In an address delivered in 1914, he claimed:

“I must say that there are some at least who, perhaps, are doing more harm than good to the cause of Christianity. I refer to those missionaries, well-meaning and good hearted, who, for a lack of a certain insight into the situation, fail to interpret the spirit of Japan in the right manner and come back to this country and paint Japanese life in darkest colors. These missionaries are frequently criticized by non-Christian Japanese, and this is one of the greatest obstacles I met in doing Christian work among the Japanese students in this country.”4

His dissatisfaction with American missionaries was so strong that Kato chose to deliver a talk about the “Need of the educated Christian Americans in Japan” at the Seventh International Student Volunteer Convention, held in Kansas City in December 1913.5 For Kato, “the knowledge of the best features of American life and civilization which all Japanese students are seeking, cannot be complete without familiarity with the principles of Jesus as exemplified in social and philanthropic institutions of America as well as in great personalities with which the country is replete.”6

According to Kato, “one significant fact about the Japanese who come here to study is that when they return home, they usually occupy positions of great influence and our problem would naturally be whether we can give these students a favorable impression of the Christian religion while they sojourn in the U.S. during the most plastic period of life.”7

When the number of students sent by the Japanese government to the U.S. increased due to World War I, how could Kato ignore their presence, which was directly connected with the government, and the future authority they would be given to spread Christianity in Japan? Thinking of the future of Japan, the world, and global peace, Kato insisted “Do not overlook the importance of influencing the Japanese students in America with genuine Christianity”8 and he advocated for a “Christian strategy for whatever we may be able to do for the cause of Christ among these Japanese students who possess a tremendous future will be definitely magnified as time goes on and any attempt on our part to extend the knowledge of Jesus Christ will have a result in the future more far-reaching than at present we are able to conceive.”9

Charles D. Hurrey, General Secretary of the Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students, (located at 124 East 28 St, New York) a part of the International Committee of YMCA, actively helped Japanese exchange students. For example, he wrote an article which listed a number of powerful Japanese who had studied in the U.S. since the 1870s.10 In order to improve the students' daily lives, his Committee held a reception for new arrivals and summer conference attendees, advocated for them in Christian homes, traded friendly correspondence and gave personal advice, distributed books and pamphlets, publishing and circulating bulletins and magazines to students, facilitated the investigation of institutions for social betterment, and organized study groups.11

Hurrey also gave Japanese students realistic advice, such as: “one should not hesitate to ask a professor or fellow-student to speak slowly or repeat if necessary.”12 Hoping for the establishment of true internationalism based on pure Christianity and believing that Japanese students, as future leaders in Japan, would contribute greatly to world peace, he advised that “prejudice is overcome, misunderstandings are corrected and lasting friendships are formed.”13 He added, “it is greatly to be desired that Japanese shall extend their acquaintance not only with American students but among Latin Americans, Chinese, Filipino, Indian, and European students” and emphasized that “there are many advantages in becoming a member of the Student Christian Association,”14

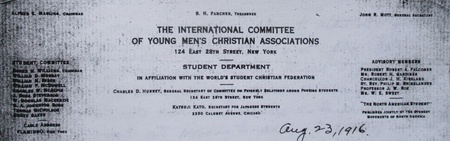

Well-supported by Hurrey in his belief that “one most fruitful method of work for Japanese was more personal than social and collective,”15 Kato became a traveling secretary and visited individual students in the country as part of his missionary work. In 1916, he listed his temporary address as the Japanese Young Men’s Christian Institute in Chicago (JYMCI, located at 2330 Calumet Avenue, which had strong relationship with the Central YMCA of Chicago) and his permanent address as the International Committee of YMCA (124 East 28th Street, New York).16

In November 1914, Kato headed for the West, visiting Japanese students in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Salt Lake City and Denver,17 and in February 1915, he visited more students in New York and throughout the East Coast.18 In March 1915, he attended the National Religious Education Association Convention held in Buffalo, New York where he delivered a speech on Japan and Japanese people, and “urged a broad, friendly policy in the treatment of Japanese and Chinese students in the U.S.”19

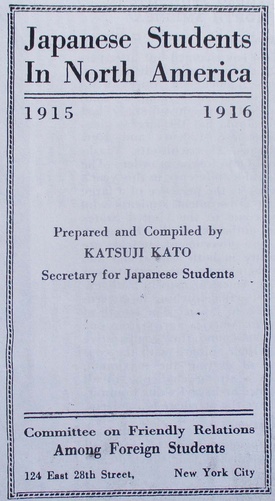

All of the information on Japanese students in the U.S. that Kato collected over his two months of travel was compiled into a report entitled Japanese Students in North America 1915-1916 and published by the Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students. When Kato visited Japanese students, he “distributed Christian literature among them, personal letters of encouragement, counsel and friendship, invited them to the summer conferences and arranged entertainment in American Christian homes.” Furthermore, he planned to organize the Christian Japanese students into an association as soon as possible, “so as to unite our effort in winning non-Christian students.”20

Beginning in 1917, a small leaflet titled The Japanese Student was being “published four times during the academic year, for the purpose of spreading the news concerning the activities among Japanese students. It is the hope of the Committee that, through this bulletin, there may be developed a consciousness of unity among them.”21 Summer camps were held at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and Japanese Christian students came from universities in the U.S. and Japan to discuss various social issues.22 Kato's work as traveling secretary for the Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students was reported at meetings of the JYMCI in Chicago.23 He made speeches on “Japanese students in the U.S. and the enterprises of the YMCA”24 and “American education.”25 It was of great concern to Kato that Japanese students in the West were developing an apathy towards churches and religion in general.26

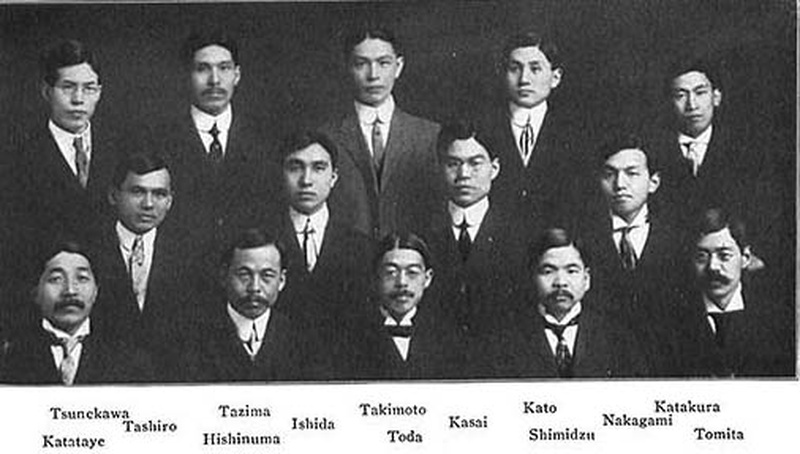

One of the tasks given to Kato as traveling secretary was to expand the JYMCI’s Tsunekawa Scholarship for Japanese students to a national level. Kato was assigned to be the head of the Scholarship committee at the JYMCI27 and worked “in close cooperation with the Committee on Friendly Relations among Foreign Students which is carrying on a country-wide campaign for securing and establishing scholarships for worthy students from abroad.”28

Acer Shiko Kusama, from Nagano, acted as Kato’s right-hand man in organizing local Japanese students. Kusama had studied at the College of Commerce and Administration at the University of Chicago and graduated in 1916,29 and was a devout Christian as well, having studied at the English Theological Seminary at University of Chicago30 and participated in the Seventh International Student Volunteer Convention held in Kansas City in 1913.31 Before receiving his degree in 1916, Kusama studied at the Divinity School of University of Chicago in 1915 32 and stayed in Chicago until 1921.33

While actively participating in the Japanese Club, the Cosmopolitan Club, the International Club and the YMCA on campus, Kusama was also a resident of and clerk at the JYMCI.34 He regularly visited Japanese students at other local universities bearing Japanese food such as sushi and mochi that Reverend Shimadzu of the JYMCI had prepared.The Japanese Student Association at the University of Illinois and the University of Michigan Japanese Student Club, which Kusama visited with Charles D. Hurrey from New York, were very grateful for Kusama’s social calls and organizing efforts.35

Kato’s performance as a missionary was well documented in an evaluation completed by the University of Chicago's President Judson, in response to an inquiry from the National Reform Association. The question of Kato’s “facility in the use of English and as to his ability as a public speaker” was a preliminary to inviting him to be a speaker or at least a representative of the Japanese people at A Preliminary Assembly to the Third World’s Christian Citizenship Conference, which was held in Pittsburg in July 1918. President Judson recommended Kato to the Association at follows: “Mr. Kato is a very interesting man, a good speaker, and usesEnglish very well. He is a man of fine character and I think he would be able to do what you wish.”36 Kato continued his traveling secretary work, studying Japanese student life in the U.S. until about 1920.37 When he gave lectures, he “delivered stereopticon slides and moving pictures illustrating phases of student life both in Japan and in American schools.”38

Notes:

1. Cap & Gown 1910, page 407.

2. Letter to Griffis dated May 28, 1895, The William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University, Reel 36.

3. The Japanese Student, October 1916, pages 4-7, Nichibei Shuho January 24, 1914.

4. “Men and World Services” addresses delivered at the National Missionary Congress, Washington DC, April 26-30, 1916.

5. Daily Maroon January 20, 1914.

6. Japanese Students in North America 1915-1916, page 2.

7. Kato, Katsuji, “The Japanese Students in the US,” The Student World, April 1917.

8. “Men and World Services” addresses delivered at the National Missionary Congress, Washington DC, April 26-30, 1916.

9. Kato, Katsuji, “The Japanese Students in the US,” The Student World, April 1917.

10. Hurrey, Chas D, “Famous Foreign Graduates Hold a Reunion,” World Outlook, July 1917.

11. Hurrey,Chas D, “International Friendship Among Future Leaders”, The Japanese Student October 1916, pages 4-7.

12. Hurrey, Charles D, “On the Threshold of a New Year,” The Japanese Student October 1917, page 8-9.

13. Hurrey,Chas D, “International Friendship Among Future Leaders”, The Japanese Student October 1916, pages 4-7.

14. Hurrey, Charles D, “On the Threshold of a New Year,” The Japanese Student October 1917, page 8-9.

15. Kato, Katsuji, The Student World April 1917.

16. Kato’s letter to Griffis dated Aug 23 1916, The William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University, Reel 32.

17. Nichibei Shuho, February 20, 1915.

18. Nichibei Shuho, May 15, 1915.

19. Buffalo Courier, March 6, 1915.

20. “Men and World Services” addresses delivered at the National Missionary Congress, Washington DC, April 26-30, 1916.

21. Japanese Students in North America 1915-1916, page 2.

22. The Japanese Student August 1917, October 1918.

23. Nichibei Shuho February 20, 1915, May 15, 1915.

24. Nichibei Shuho, September 25, 1915.

25. Nichibei Shuho, October 30, 1915.

26. Nichibei Shuho, February 20, 1915.

27. Nichibei Shuho, July 17, 1915.

28.The Japanese Student February 1917.

29. University of Chicago Convocation Program, September 3, 1915, University of Chicago Magazine April 1917.

30. University of Chicago Annual Register 1914-1915.

31. University of Wisconsin at Madison Yearbook 1915.

32. University of Chicago Annual Register 1915-1916.

33. California, Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists 1882-1959.

34. World War I Registration.

35. The Japanese Student February 1918, page 125 and 129.

36. Letter to President Judson, April 23, 1918, Letter of President Judson dated April 25, 1918, University of Chicago Office of the President Harper, Judson and Burton Administration Records 1869-1925, Box 53, Folder 20, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago.

37. World War I registration, 1920 census.

38. The Honolulu Advertiser, Dec 11, 1917.

© 2022 Takako Day