Reportage or Art?

Wakaji produced countless individual portraits, documented civic activities like parades and cultural events, and recorded private celebrations such as weddings, club ceremonies, and graduations. He did a considerable amount of advertising photography too, and he was hired by the military to document their endeavors.

Examples of his varied photographic activity abound. In 1929, for instance, Wakaji photographed the cheering citizens of Hiroshima as they welcomed home the Hiroshima Commercial High School baseball team after they won the Japanese national tournament. He extensively documented, in 1936, a trade fair at the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, now called the Atomic Bomb Dome or Hiroshima Peace Memorial. In 1942, he photographed the departure ceremony for the Manchurian Youth Corps, a group of young farmers, fifteen to twenty-two years old, who were being sent to cultivate land in Japanese-occupied Manchuria.

Wakaji had accomplished his goal. In many ways, he became for Hiroshima what Miyatake had been for Little Tokyo in Los Angeles—a chronicler of personal lives, group activities, and city events.

Fundamentally, Wakaji was always an art photographer in spirit, even while documenting the lives of those living in Hiroshima, or earlier, when he was a part of the Japanese community in Los Angeles. His early work in Los Angeles tended to be distinctly divided between art photography and photography as document. His art photographs were typically done in the prominent style of the time, Pictorialism—soft-focus, subtly toned, and emotive (Fig. 19).

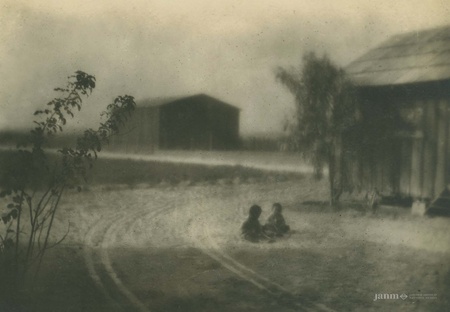

In a few cases, his early work was modern and semi-abstract. Either way, they were done intentionally as art and without a practical purpose. His documentary work, such as the sensitive, poetic panoramas of family farms were intended to represent the character of the lives of Japanese Americans working on Los Angeles farms.

They foreshadow his later work in Hiroshima, which consciously or unconsciously, blend his two approaches, art and documentation. His work might be described best as artful documentation, sometimes emphasizing the artistic and other times reportage.

Photography as documentation is a tradition going back to the beginnings of photography, including Japanese photography. Mid-nineteenth century European photographers recorded far-off lands for an audience eager to explore distant places at a time when travel was expensive, time consuming, and dangerous. Felice Beato, who lived in Japan from around 1863 to 1885, captured the dramatic changes from the Edo period to the beginning of the Meiji era. His carefully considered photographs were often staged scenes of individuals, genre subjects, and Japanese customs. As was frequently the case when Europeans depicted other cultures, it was through biased, post-Darwinian eyes, which romanticized and exoticized their subjects.1

Documentary photography throughout the world, particularly of active urban scenes, became increasingly viable as photographic emulsions became fast enough to record the hustle and bustle of city streets. Social documentary photography took up societal causes beginning around the turn-of-the-century with photographers Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, who recorded deplorable urban living conditions and abusive child labor practices in the United States. Later, photographers like Dorothea Lange revealed the deprivations of the Great Depression in America, and she also recorded the shameful incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

In Japan, crusades for social causes were not undertaken, but a fuller appreciation of the narrative potential of photography and its ability to record Japanese society and culture became highly developed during the 1920s when photographic magazines and newspaper supplements were produced in large tabloid size and printed in high-quality rotogravure.2 This continued into the 1930s. Hiroshi Hamaya, for example, who was born and raised in Tokyo, began to document that city from both air and ground, and later, in 1939, he went to the rural coast along the Sea of Japan to document age-old traditions and customs before they died out. These were widely seen in magazines, as were documentary works by many Japanese photographers.

Photojournalism, a more specific form of documentary photography, developed in the 1930s. Photographers like Ihee Kimura used a small format camera, the thirty-five millimeter Leica, to capture candid scenes. As political tensions expanded throughout the decade before World War II, particularly with onset of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, photojournalism turned increasingly into government propaganda.

Certainly, Wakaji’s interest in a documentary approach to photography would have been encouraged by the trends of the late 1920s and early 1930s. This may, in part, suggest why he did not pursue, to the same degree as he did in Los Angeles, pure art photography as a distinct and separate practice while in Hiroshima, but instead combined his photographic instinct for art with documentation.

New directions in art photography did not escape Wakaji’s notice, however. The development of art photography magazines, along with an increasing number of international photographic exhibitions and catalogs, informed him of the newest developments in art photography throughout Japan, as well as the world at large.

By the end of the 1920s, avant-garde styles in Europe were well represented in the books and magazines available in Japan. In 1931, the German International Traveling Photography Exhibition, based upon the Film and Foto exhibition held in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1929, was shown in Tokyo. Like a shockwave, it further spread the latest in European and American photography to Japan, including movements like Surrealism, German New Objectivity, and the aesthetics of the Bauhaus. Evidence of his receptiveness to these modern influences can be seen in a number of images produce by Wakaji of buildings and signs taken at extreme angles. These photographs are distinctly reminiscent of Bauhaus photography, as are photographs that he did of modern European-style furniture.

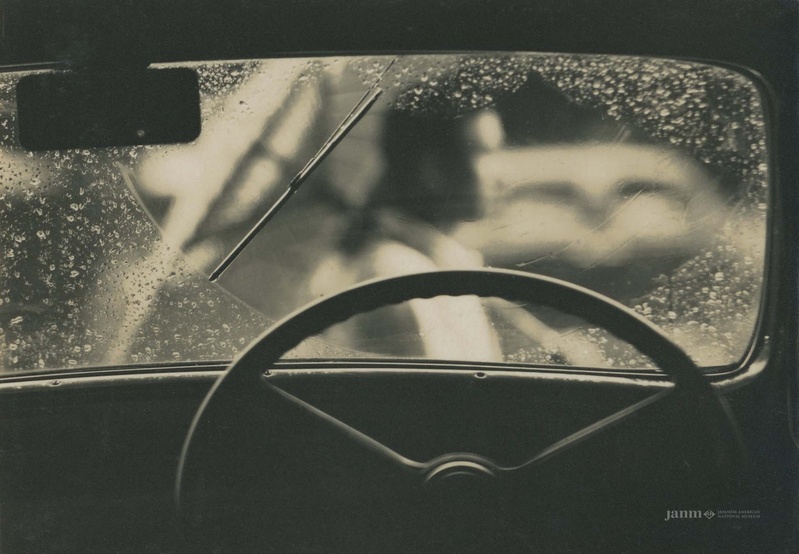

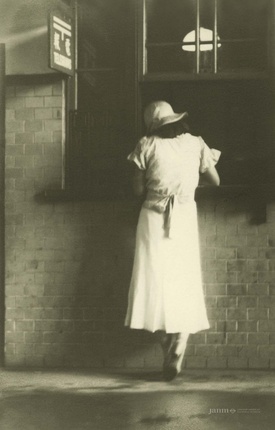

Among the best of his work done in Hiroshima are tender photographs of simple street scenes, like a man pulling a cart in the snow (Fig. 20), the back of a woman bathed in light as she stands at a counter (Fig. 21), the sweep of a wiper across a rain-covered windshield (Fig. 22), or the Matsumoto children washing articles in the street as trollies pass (Fig 23). These pictures feel personal and intimate, not merely descriptive or coldly informative. They are loving memorials to a city, this particular city, Hiroshima. Of course, Wakaji could not have known its fate at the time.

War

With the onset of World War II, resources in Japan became increasingly committed to military purposes, and it was difficult for Wakaji to obtain photographic supplies. It became apparent to Wakaji that he must close the business and move his family since they lived above the studio. Loading a horse-drawn cart with all of his equipment, remaining supplies, negatives, prints, and personal belongings, he relocated his family to his parent’s home in the village of Jigozen, in Hatsukaichi, some ten miles away from Hiroshima.

At his parent’s home, he stored his negatives and prints in one room, and he set up a tiny studio and darkroom in another part of the house so that he could continue to photograph during the war. At one point, Wakaji was conscripted to work for the war effort and was assigned to a coal mine in Ube-shi, Yamaguchi Prefecture.3 Working there, he developed a serious lung disease, likely acerbated by his chronic cigarette smoking. The illness plagued him for the rest of his life.

Wakaji’s family may have felt safer living away from the center of Hiroshima, which due to its military base was a target for bombardment, though in fact it was not bombed with conventional weapons by US forces.4 As it happened, the house in Jigozen was attacked, if unintentionally. In 1945, an airplane from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet unleashed one of its bombs, perhaps to lighten its load or by mistake, as there was no military target in the immediate area. It hit the house next door, killing the five inhabitants. A part of the bomb blast, or shrapnel from it, hit the Matsumoto home, destroying Wakaji’s small studio and all of his camera equipment. Happily, no one was injured in the Wakaji household, and the photographs, stored away from the studio, were unscathed.

Decades later, in a conversation with family, Tei recalled the nuclear attack on August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m. In Jigozen that morning, she was laying out laundry to dry in the sun when she saw a glittering light in the sky above Hiroshima. It started to spread toward her, and she wondered if it was a shockwave or the impact of an explosion. In the city, one survivor described the light as a “sheet of sun.”5 She, like the residents of Hiroshima, could not comprehend the full measure of what was happening, but all would soon come to understand, personally, the unique horrors of atomic weapons.6 At one point following the blast, according to Matsumoto family lore, Wakaji and Tei wheeled a cart into Hiroshima to look for relatives near the former studio, which had been obliterated. Among the injured and dying, they found only one relative, a cousin of Tei’s. They laid him on the cart to transport him back home, but he died before they reached Jigozen.

Wakaji lived through the war and passed away in Jigozen in 1965, at the age of seventy-six years old. Tei continued to live in the family home for another thirty years, passing away in 1995 at age 101. Surprisingly, the boxes of negatives and photographs remained undisturbed until 2008, when a grandson, Hitoshi Ohuchi, who was also a photographer, recognized their value and arranged for them to be placed with the Hiroshima City Archives.

These photographs that so artfully documented the people and city of Hiroshima before the atomic bombing seemed, like the proverbial cat, to have had several lives. They narrowly missed being destroyed by a wayward bomb, and then they were spared destruction from the first use of an atomic weapon. Most importantly, these photographs by Wakaji turned out to be the largest-known photographic archive of pre-atomic-bombed Hiroshima. Today, our knowledge of the city’s horrific fate lends a pall of melancholy over these tender images. They bear the weight of history.

Notes:

1. Alona C. Wilson, “Felice Beato’s Japan: People, An Album by the Pioneer Foreign Photographer in Yokohama,” MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2010, (accessed 4/11/2022)

2. Kaneko Ryuichi, “Realism and Propaganda: The Photographer’s Eye Trained on Society” in The History of Japanese Photography (Houston, 2003), 185.

3. Wakaji was in his 50s during the war, and conscription of able body men was limited to those between 17 and 40 years of age until 1945, when the cap was increased to 60.

4. F. G. Gosling, The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb (DOE/MA-0001; Washington: History Division, Department of Energy, January 1999), 45-47; Craig, Nelson, “Bombing Hiroshima,” Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective (Ohio State University, August 2015), (accessed 5/4/2022)—some Japanese civilians went to Hiroshima seeking safety because it had not been conventionally bombed.

5. Hersey, 8.

6. Chairman’s Office, “The United States Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki” (Government Printing Office, Washington, 1946), (accessed 5/5/2022).

* * * * *

This essay was written in conjunction with the Japanese American National Museum’s online exhibition, Wakaji Matsumoto—An Artist in Two Worlds: Los Angeles and Hiroshima, 1917–1944, which highlights Wakaji’s rare photographs of the Japanese American community in Los Angeles prior to World War II and urban life in Hiroshima prior to the 1945 atomic bombing of the city, and artistic photographs of daily life in both cities that were created as a form of personal expression.

View the online exhibition at janm.org/wakaji-matsumoto.

*All photos by Wakaji Matsumoto (copyright Matsumoto Family)

© 2022 Dennis Reed