The coming of World War II and the mass confinement of West Coast Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066 shuttered the community press. Literary activity did continue, to a limited extent, within the WRA camps, where inmates published stories and poems in camp newspapers and in reviews such as TREK at the Topaz camp. Except at Poston, which had a handful of black staffers, and in some areas near the Arkansas camps, confined Japanese Americans had little opportunity to interact with blacks. Perhaps as a result, the wartime literary output of the Nisei all but ignored their presence and condition.

One of the few creative works from camp newspapers to feature African American characters is Frank Hijikata’s “Mandy’s Dream,” which appeared in the Tulean Dispatch Literary magazine in 1942. In it, Mandy Jones, a slave who is in agony after being beaten and berated by her white master, Arnall Rankin (his name taken from those of liberal Georgia governor Ellis Arnall and race-baiting Mississippi congressman John Rankin) falls asleep. She dreams that she is in Heaven, where she is welcomed by the Lord and the saints, and given a large beautiful house to live in, while Rankin gets a miserable shack. She protests, in broken dialect, “Ah’s just a slave, a n-----r at dat. Dis can’t be mah home.” It is explained to her that she is being rewarded for her good deeds on Earth, while Rankin is punished for his misdeeds.

While the story did at least point to the horrors of slavery, more than Gone With the Wind or other popular writings of the era, this parable of the meek inheriting the (after) Earth offered a flat narrative and had no strongly developed characters. As such, it betrayed the kind of literary weaknesses associated with “protest fiction” such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin that the young James Baldwin deplored in his landmark 1948 essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel”.

Interestingly, black characters figured strongly in two works published North of the border. The Canadian Nisei newspaper New Canadian, which originally began publishing in Vancouver in 1938, had been forced to leave the West Coast in 1942 as part of the mass removal of Japanese Canadians, and had set up operations in the confinement site of Kaslo, BC. Its June 30, 1943 issue featured a story entitled “Lost My Baby, Lost Her fo’ Good.” The author was Hugo Yamamoto, a jazz enthusiast and sometime music critic for the New Canadian. The story tells the tale of a man named “Jess” (whose ethnicity is not described) who has been depressed since Jenny, his girlfriend, left him. In order to forget her, he frequents a nightclub with a “colored band” and “ebony dancers.” He gets so excited by the dancers and by the voice of the blues singer “Ma” Jordan that he collapses in his chair.

A more pointed and dramatic tale was “Althea and the Negro,” which ran in the August 11, 1948 issue of the New Canadian. The author was a young Nisei who went by the pseudonym “Jess” (and who nearly 50 years later would publish Ignomy, a novel about the Japanese Canadian camps). “Althea and the Negro” tells the story of Ted, an African American in Savannah, Georgia who meets a white woman, Althea, at a clandestine interracial soirée. The two slowly fall in love. However, as scandalous rumors spread about their upcoming wedding, Althea receives anonymous messages threatening violence if she does not leave her lover. One night Ted and Althea are kidnapped by a group of masked men. “Jess” starkly describes the ensuing lynching, leaving the reader with a sense of horror and pathos.

In the years after World War II, Japanese American newspapers resumed operations on the West Coast and new journals emerged to serve growing communities in cities such as New York and Chicago. The Pacific Citizen provided national news coverage. A pair of glossy photomagazines, Nisei Vue and Scene, boosted positive community images. A handful of Nisei, including S.I. Hayakawa, Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi, Yoné U. Stafford, Ina Sugihara, Larry Tajiri, Hisaye Yamamoto, and Wakako Yamauchi, wrote for the African American and interracial press.

Yamamoto later produced the powerful memoir “A Fire in Fontana” (1985) on her experience working as a columnist for the Los Angeles Tribune and how an incident of racist terrorism shaped her. Yet amid all this newspaper activity, literature by Nisei all but disappeared from the ethnic Japanese press, which no longer included Sunday literature pages, and editors ceased publishing creative writing and book reviews. Both as a cause and effect of the lack of markets, most prewar poets and story writers stopped producing material, or found outside venues for publication.

Within this reduced output, only a few literary works of any kind referenced African Americans. In 1949, Ken Hayashi devoted an installment of his recurring column “In this Corner,” in the bilingual New York newspaper Hokubei Shimpo, to describing the clients of a set of tawdry bars in Harlem—Hayashi summed them up as “Unhappy people haunting Harlem ginmills laughing like hell and fooling everyone but themselves.” In the days that followed, there was spirited correspondence in the pages of Hokubei Shimpo, both pro and con, over the stereotypical depiction of “Negroes.” A Nisei reader slammed Hayashi for dishonesty and abusing the good will of the Harlemites. “This kind of indulgence in ginmill elbow-rubbing with other minorities, to imply tolerance and understanding, and then to make back-handed remarks about them, is just as insidious and vicious a racism as the outright racism of the K.K.K.” Hayashi responded that, so far from being racist, his intent was to elicit sympathy for a persecuted minority group. Si Spiegel (future husband of Nisei activist Motoko Ikeda-Spiegel) countered in a letter that if Hayashi had indeed meant to convey sympathy, he should not have chosen such a subject: “Here is an article about the Negro that would perpetuate the white supremacist stereotypes of the drunken, shiftless, indolent, lewd and unhappy Negro people.”

Another work that featured African American characters was Hisaye Yamamoto’s short story “The Brown House,” which was published in Harper’s Bazaar in 1951. The story revolves around Mr. Hattori, an Issei farmer who has developed a gambling addiction. One evening, he enters a Chinese gambling club, while his wife and children are obliged to wait for him in a car outside. An African American gambler, desperate to evade the police, enters the car and hides inside, with Mrs. Hattori’s begrudging consent. After Mr. Hattori returns, and they start off, the man asks to get out of the car. Rather pathetically he expresses his gratitude, which he poses in terms of interracial solidarity. After he leaves, Mr. Hattori, surprised by the appearance of a stranger, expresses anger at his wife for allowing the man to stay in the car with her and the children—he uses Kurombo, a derogatory term for Blacks. His harsh words reveal the previous gambler’s ideas of racial solidarity as naïve and absurd. While the African American gambler is more of a device for the author’s coruscating irony than a fully realized individual, the man’s mix of visible difference and invisibility (in hiding himself among Nikkei) suggests a kinship with the unnamed narrator of Ralph Ellison’s classic novel Invisible Man, published the following year.

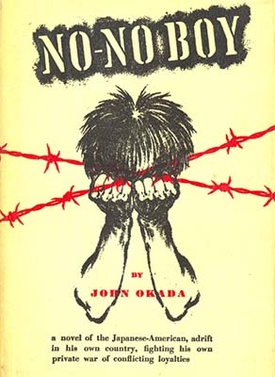

Another postwar work to bring in African Americans is John Okada’s now-classic 1957 novel No-No Boy. In the initial pages of the novel, Ichiro, a Nisei jailed for wartime draft resistance, returns to his former home in Seattle, and is victimized when he passes a pool parlor on Jackson Street that has now become a hangout for a raucous crowd of Blacks:

“Jap!”

His pace quickened automatically, but curiosity or fear or indignation of whatever it was made him glance back at the white teeth framed in a leering dark brown face which was almost black.

“Go back to Tokyo, boy.” Persecution in the drawl of the persecuted.

The white teeth and brown-black leers picked up the cue and jugged to the rhythmical chanting of “Jap-boy, To-ki-yo; Jap-boy, To-ki-yo . . .”

Ichiro responds with a racist epithet under his breath as he moves on. His former feeling of tolerance is dented by this sad spectacle (as the author terms it) of “Persecution in the drawl of the persecuted.”

In contrast, Okada relates a story of interracial friendship later in the work. Gary, another Nisei draft resister, tells of Birdie, an African American war veteran who works at a foundry with him. Birdie defends Gary when the other workers are hostile to him. In retaliation, racist foundry workers loosen the lugs of Birdie’s car, which flips over at high speed—fortunately he escapes uninjured. The character of Birdie, though only presented in a secondhand portrait, allows Ichiro (and author Okada) to find “a glimmer of hope” for a happier future.

The first generation of Japanese American writers to integrate African American characters into their work also shared some common traits. One was extreme youth: Vincent Tajiri was 16 years old, Kenny Murase 19, and Ayako Noguchi and Frank Hijikata 20 each when their respective pieces appeared. The Rendezvous of Mysteries came out on the eve of its author’s 22nd birthday, while Joe Oyama (if he was indeed the author of “Lady in a Bathrobe”) was only 24 when it was published. The Canadian writers Hugo Yamamoto and “Jess” were each in their mid-twenties when their works appeared. The postwar writers, who portrayed more complex and ambivalent interracial encounters, were themselves barely into their 30s. Another was the writers’ tendency to use their African American characters as foils, through whom they talked about the condition of Japanese Americans. (Similarly, while in camp, Murase would produce a series of short sketches featuring “Little Esteban”, a Mexican-Native American “spirit of Poston” who served as an interlocutor for the narrator).

© 2022 Greg Robinson, Brian Niiya