Along with publishing the opinions of intellectuals and government officials, The New Republic remained one of the few mainstream periodicals to offer a forum for the views of Japanese Americans themselves. In prewar years, Nisei activists Franklin and Robert Asahi Chino wrote letters to the New Republic in response to their articles. The first publication from a Japanese American was architect Ted Nakashima’s provocatively-titled article, “Concentration Camps: U.S. Style,” which appeared in the June 15, 1942 issue.

Nakashima, a Nisei architect (and the brother of the more celebrated architect and furniture designer George Nakashima), detailed the overnight change in his life after he was forced to leave his Seattle home for the spartan conditions at the army assembly center “Camp Harmony” at Puyallup, Washington. He depicted the woeful squalor of camp life, and implored readers to let Japanese Americans leave camps so that they could participate in the war effort in equal fashion. Nakashima also introduced to readers the concept of “gaman,” or silent resilience, a term now commonly associated with the wartime Japanese American experience.

When Nakashima’s article was published, it immediately caught the attention of readers. In response, Army officials refuted Nakashima’s descriptions and pressured The New Republic’s staff to “investigate” the conditions at Camp Harmony. The anonymous investigator eventually published a response in the January 18, 1943 issue. While offering support for Nakashima’s original message regarding the harsh realities and injustice of the camps, the investigator’s article nevertheless stated that Nakashima had exaggerated the poor conditions of camp life. The investigator also referred to “Japanese,” eluding the fact that the majority of those confined were American citizens.

Although The New Republic’s decision to print the “response” reflected poorly on the values of the magazine, at the same time it is worth noting that the editorship faced army pressure that amounted to official censorship, and that the magazine’s eventual “response” came long after the Assembly center had closed, and the controversy had passed. Several journalists, however, took issue with The New Republic’s investigation and wrote letters to the editorial board criticizing their attempt to downplay Ted Nakashima’s original article. Several weeks later, in its April 12, 1943 issue, The New Republic’s editors produced a follow-up apology for some of the language of the response article, but maintained that its investigation had itself been genuine and legitimate.

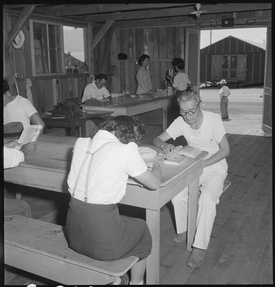

On January 1, 1943, in the wake of the revolts at Poston and Manzanar, The New Republic published an article, “Trouble Among Japanese Americans,” authored by the celebrated sculptor and designed Isamu Noguchi. Noguchi’s article (which took in part from a rejected essay he had written in camp on commission from Reader’s Digest) presented a vivid portrayal of his own incarceration at the Poston Concentration Camp in Arizona and his observations of communal divisions created by the camp experience.

Like Ted Nakashima, Noguchi notes the presence of armed guards, barbed wire, and the desolate conditions within the camps, despite the efforts of the War Relocation Authority to improve life for the inmates. Noguchi concludes the only remedy for Japanese Americans is to leave the camps and resettle in American society outside of the West Coast.

Although the Nakashima and Noguchi pieces were the only two full-scale articles authored by Japanese Americans, several letters to the editor sent by Japanese Americans appeared in the pages of The New Republic during this period. On March 6, 1944 Teiko Ishida, the acting national secretary of the Japanese American Citizens League, extolled the creation of an all-nisei combat unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Meanwhile, she encouraged readers of The New Republic to subscribe to the JACL’s newspaper The Pacific Citizen.

In response to Ishida’s letter, The New Republic published a letter written by Kazuyuki Takahashi. Takahashi, a former Stanford University medical student who had been incarcerated at the Manzanar concentration camp, countered Ishida that even if allowing Nisei into the army was a positive step, the U.S. government still denied Japanese Americans equal rights in supporting the overall war effort. In his response, Takahashi noted that the Army still barred Japanese Americans from serving in other branches of the armed forces, and that Nisei like himself required government passes to venture beyond the barbed wire of the camps. Takahashi concluded that the JACL did not represent the community, and argued that readers should know that other Japanese American organizations existed and were more committed to democracy.

Surprisingly, Roger Baldwin of the ACLU wrote a letter in response to Takahashi. Baldwin agreed that the Army was still racially segregated, but proposed that Japanese Americans nonetheless should use this newfound opportunity to enlist and pressure the army to change the policy. Additionally, Baldwin praised the Japanese American Citizens League, stating that while other organizations existed, none had as much national political influence as the JACL.

Takahashi thereupon replied to Baldwin’s letter in the pages of The New Republic. Takahashi asserted that the gains made by Japanese Americans could not reduce the feeling of second-class citizenship generated by ongoing racial discrimination. Likewise, Takahashi insisted that while Baldwin might be correct to praise the JACL for its lobbying efforts, the organization did not broadly represented the views of the Japanese American community, and slammed the JACL leadership for its attacks on those who offered well-meaning critiques.

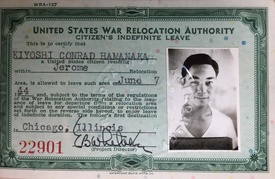

The last letter, and perhaps one of the most moving, was written by Japanese American writer and editor Conrad Hamanaka (later known as the actor Conrad Yama). In December 1945, shortly after he published a set of controversial articles on the topic in the Pacific Citizen, Hamanaka sent a letter to The New Republic to raise awareness of the plight of the thousands of Japanese Americans still detained at Tule Lake Segregation Center. While most mainstream publications presented the Tule Lake inmates as “disloyal” and deserving of punishment, Hamanaka took a more human position, and characterized them as individuals subjected to the extreme duress of the incarceration, who had signed renunciation papers as an act of protest rather than disloyalty. Hamanaka, noting the end of hostilities, implored his readers to provide legal support for those threatened with deportation, as such an action would further erode civil liberties.

The New Republic stands as a rare example of a wartime media outlet that presented a nuanced view of Japanese Americans. Although The New Republic praised the work of the War Relocation Authority without question, and staunchly supported President Franklin Roosevelt and his administration’s policies, it published several articles that helped to refute the longstanding narratives of “military necessity” behind forced removal and presented the consequences of the incarceration for its victims. It should be noted that throughout the war, Japanese Americans followed the publication of articles in The New Republic related to their incarceration. Camp newspapers, such as The Manzanar Free Press, noted the publication of Carey McWilliams’s reports on racism and forced removal, along with the appearance of letters by inmates such as Takahashi. In sum, the pages of The New Republic provided a unique forum for the discussion of the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans as it unfolded.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen