The Japanese attack on the U.S. fleet in Hawaii on December 7, 1941 triggered war between the two countries. On this side of the Pacific, throughout the entire continent, that date also marked the beginning of a peculiar war against hundreds of thousands of Japanese immigrants living in numerous countries, who were promptly accused of being “foreign enemies.”

In the United States, on the eve of that fateful day, Japanese Americans were preparing for the upcoming Christmas and New Year festivities. These immigrant communities were already well integrated into the U.S. economy and culture. Nevertheless, on that Sunday afternoon, FBI agents showed up at their homes and arrested close to 2,000 people considered “leaders” of the large community, which numbered more than 120,000. Those arrested in that first raid included teachers of the Japanese language, karate, kendo, and ikebana, as well as Shinto cultural leaders and fishermen.

Terminal Island, located off the port of Los Angeles, was home to more than 3,000 Japanese immigrants and their families who earned their living from fishing or worked in fish and shellfish packing plants. The island was placed under martial law and the army took control. Immigrant fishermen were considered dangerous due to their livelihood and were accused, without any evidence, of supporting a potential invasion by the Japanese navy. Rumors, spread by the press and radio, created an environment that was hostile not only to the Japanese immigrants but also their descendants, who were U.S. citizens. The Los Angeles Times newspaper reported that evicting the community living on the island “had cleared the foreign threat.”

Under pressure from the U.S. government, Mexico’s Secretary of the Interior, Miguel Alemán, who was in Washington, D.C. at the time, ordered all people of Japanese descent living near the border to immediately pack up and move to Guadalajara and Mexico City.

For all of the Japanese communities on the continent, 1942 began with some very ominous signs. The government of Baja California ordered all fishermen to leave their workplaces and their boats within five days and move to Mexicali, Tijuana, and Ensenada. Once there, they were ordered by government officials to resettle in towns far from the coast within 15 days. From then on, immigrants and their families were required to notify the Ministry of the Interior of their location at all times and had to request permission to move elsewhere. In total, more than 1,000 people were displaced in Baja California.

The port of Ensenada had been settled by a community that brought innovative techniques to improve the capture of various marine species. The fishing industry in Ensenada was growing in response to increasing demand for lobster, tuna, and abalone, which Japanese immigrants began fishing in the first half of the 1910s along the Baja California peninsula. By the late 1920s and early 1930s, Ensenada’s two packing plants were supplied by Japanese fishermen. Many had initially come to Mexico with contracts to work for two Japanese entrepreneurs based in California, Masaharu Kondo (in San Diego) and Shin Shibata (in Long Beach). The fishermen brought with them techniques that were previously unknown in Mexico such as abalone drying, pole fishing, the use of live bait, and others.

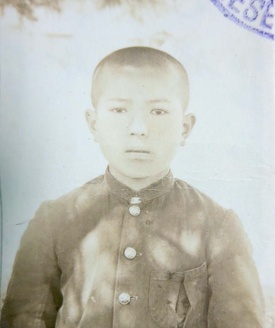

Takeshi Morita was one of the fishermen who settled in Ensenada and became a Mexican citizen. On the day before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, working on the Sun Harbor boat, Takeshi and his coworkers set off to fish the open sea, as they always did. Unaware that the war had begun, they docked in the port of San Diego on December 10, 1941 to unload the fish they’d caught from the rich waters of Baja California. Morita and his crew were immediately arrested by U.S. immigration authorities. They were then held by the FBI, because as fishermen they were considered “dangers to the public peace and the security of the United States,” and were accused of carrying out “espionage and subversive activities”, despite a total lack of evidence.

The FBI and other U.S. authorities disregarded Morita’s Mexican citizenship, which he had obtained seven years before, and proceeded to interrogate and fingerprint him. The war against the Japanese thus took on a clear racial character. For tens of thousands of people like Morita, holding Mexican or American citizenship was irrelevant. To the U.S. military, Japanese immigrants and their descendants were part of the Japanese imperial forces, since “Japanese blood” ran through their veins, they said.

Under this pretext Japanese immigrants and their children in the United States were transferred to 10 internment camps. This measure also had direct repercussions for the immigrant community in Mexico. Japanese fishermen who lived in Baja California or who had docked in U.S. ports prior to the war were arrested. Typically, after unloading their catch, the fishermen stayed in the United States for a few days. On December 7, more than 90 fishermen who had legally entered the country were prevented from returning to Ensenada or Tijuana, where they had lived for more than a decade. They were never able to return to their homes in Ensenada again! All were detained in the internment camps and deported to Japan after the war ended in 1945.

The case of Takeshi Morita was somewhat different because he was a Mexican citizen. Morita was born in Yamaguchi Prefecture on July 2, 1914. His family was very large, as he was one of nine siblings from a farming family. Unfortunately, Takeshi’s father died in 1928 and his mother, unable to support nine children, decided to send her young son, then 14 years old, and Mizuko, his older sister, to live with their uncle Ryutaro Muramoto, in Tijuana. Takeshi and his sister arrived in Tijuana that same year and began helping their uncle with his farm labors. Takeshi, who had reached high school in Japan, enrolled in a primary school to learn Spanish. From then on, he worked in various jobs while continuing his studies. The next year, Takeshi started cleaning rooms at the Savoy Hotel, where the manager, Jose Takaki, was also a Japanese immigrant. That same year, Takeshi enrolled in high school.

In 1930, Takeshi moved to Ensenada to live with his sister and her husband, Kazuto Morita, an immigrant who had already become a Mexican citizen. Takeshi worked at the Central Market, selling vegetables. In 1933, at the age of 19, he started the paperwork to become a citizen, motivated by the prosperity of the Japanese community in Mexico and the fact that many immigrants had already taken that important step.

Having obtained his Mexican citizenship, in 1935 Takeshi began working at a grocery store, El Edén, owned by another Japanese immigrant, Francisco Ishino. He worked and lived there for several years, and in 1938, decided to become a fisherman. These events influenced his life in a transcendental way, as we will see later in his story.

Attracted by the booming fishing industry and its good wages, the young Morita began spending most of the year in the fisheries, although he continued to live in Tijuana and worked at El Edén when on land. The boats Morita fished on during the pre-war years belonged to U.S. companies headquartered in San Diego.

Although he was a Mexican citizen working for a U.S. company, racism and hysteria among immigration authorities quashed any dissenting opinions, even within the Justice Department. They asserted that Morita should remain under arrest because of his livelihood and his familiarity with the coastline from California to Panama, even though that wasn’t entirely true. In addition, they said, El Edén grocery store was a “center of Japanese activity” and because of his background, Takeshi was still loyal to the Japanese emperor and therefore very dangerous. Throughout the long interrogations he was subjected to, Morita stated repeatedly that he intended to remain in Mexico and confirmed his loyalty to the country he had chosen as his home.

During his internment in the United States, Takeshi Morita was held in various detention centers and internment camps. After being arrested, he was sent to the San Diego County jail, and transferred through several immigrant detention centers over the following months. In July 1942, while his legal status as a prisoner was still unresolved, he was permanently interned in a camp in Livingston, Louisiana, on the other side of the United States. In summer 1943 he was sent to the internment camp at Fort Missoula, Montana, on the Canadian border, and the following year he was moved to the camp in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was finally transferred to El Paso, Texas, and then sent back to Mexico.

During those three years, Takeshi suffered the agony and uncertainty of having been illegally arrested, along with the always latent possibility that he would be freed, as eventually happened. But perhaps the most tragic aspect of his experience was the death of his sister’s husband in February 1943. The forced resettlement of his sister’s entire family from Ensenada to Mexico City was a violation of their rights as Mexican citizens in and of itself, but the news of the Kazuto’s sudden death was devastating for Takeshi, as his sister was then pregnant with her fifth child.

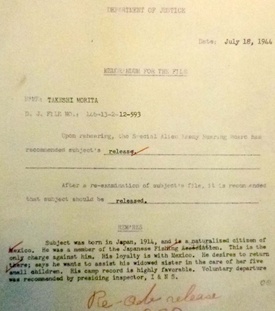

Upon learning of his brother-in-law’s death, he redoubled his efforts to obtain his release, which some U.S. citizens of Japanese descent had successfully done. Trapped in a bureaucratic maze, after many months the Attorney General of the United States, Francis Biddle, ordered his release in July 1944. However, he wasn’t actually released until the next year, when the war had almost ended.

All the officials at the internment camps where Takeshi was held, and even the FBI itself, described his conduct as “excellent” during the three years of his internment, and even went so far to say he was a “model internee”. Eventually, there would be recognition that the basis of the illegal arrest of Morita and thousands more prisoners of Japanese descent was hysteria. Morita was able to reunite with his sister in Mexico City in February 1945, and lived there for the rest of his life, leaving his work as a fisherman behind forever.

© 2022 Sergio Hernández Galindo, Kiyoko Nishikawa Aceves