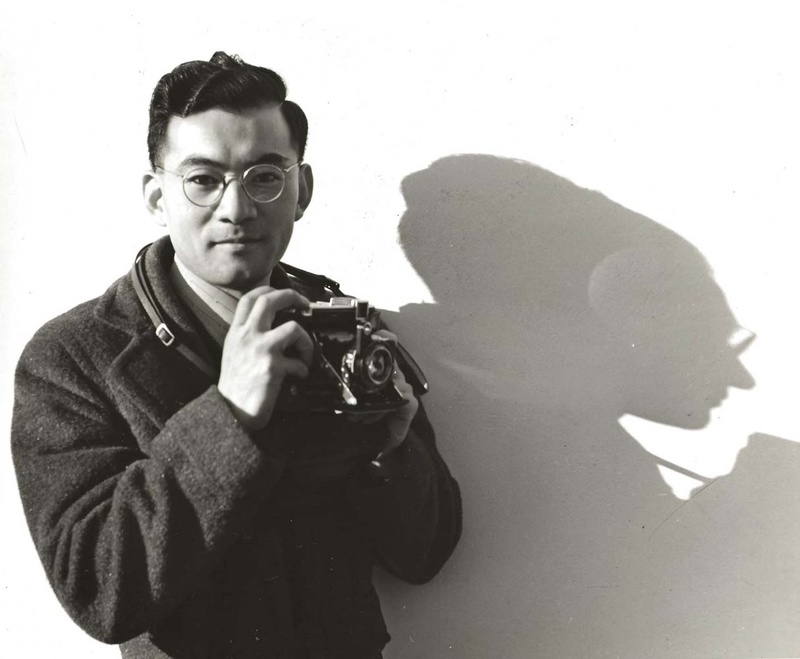

Toge Fujihira (whose family name was sometimes reported as Fujihara) left the West Coast in the years before World War II and settled in New York, where he distinguished himself as a photographer and documentary filmmaker. During the postwar era, he established himself as a professional cameraman and photographer, capturing prize-winning photos and films of landscapes and people in the United States and around the world.

Toge Fujihira was born Kazuo Togo Fujihira in Seattle, Washington on January 18, 1915, the eldest of four children of Chu (AKA Fuji) and Kiyo Fujihira. During his teen years, he starred as an athlete. He played for the University Nippons team in the Nisei basketball league organized by Bill Hosokawa, and for the University District football team coached by Roy Nakagawa. Perhaps in conjunction with his sporting activities, he adopted the nickname Toge during this time. He also showed a strong community consciousness. He was an Eagle Scout, and worked as a counselor at a summer camp for Nisei boys sponsored by the Salvation Army.

At 18, Toge enrolled at the University of Washington. While at UW, he contributed a number of articles to the Japanese American Courier and the Rafu Shimpo. One was a short story that recounted a racist incident involving a Japanese American student, Charles Richi, who receives an invitation from a white sorority for a “fireside” dance, the sorority girls having mistaken his name for the white name “Ritchie.” When Charles arrives, he sees clearly that none of the women wants him there, and a house mother eventually tells him to leave. He then realizes that, despite his being invited, his Japanese identity made him unwanted.

After receiving his bachelors from the University of Washington, Fujihira went on to pursue a Masters in Zoology. In 1938, after completing his Master’s degree, he moved to New York City and roomed with two other transplanted West Coasters, journalist Tooru Kanazawa and novelist George Furiya. Meanwhile, he changed careers. During his college years, Fujihira had already been an enthusiastic amateur photographer. As Fujihira’s friend Bill Hosokawa later recorded in the Taihoku Nippo, once in New York the young man began studying to become a professional photographer, and went to meet various photographers as part of his studies.

In April 1939, working under the name “T.K. Fujihira,” Toge submitted a photo of young people to an international Y.M.C.A. Amateur photography contest. The photo was awarded honorable mention, representing Fujihira’s first mainstream recognition. Then in May 1939, under the tagline “Seattleite in New York City,” Fujihira reported for Shin Sekai and Taihoku Nippo on the New York World’s Fair and its Japanese pavilion. These articles provided Fujihira a platform for discussing the Japanese presence in New York City. In 1940-41, Fujihira was employed as a staff photographer and art editor by the Japanese American Review, the English-language pro-Japanese newspaper in New York.

In addition to his still photography, in 1940 Fujihira began work as a filmmaker. His first project was a two-reel 16 mm amateur production of Anton Chekhov’s The Boar, with an all-Nisei cast led by actor Shiro Takehisa.

On November 22, 1941, Toge Fujihira married Mitsue Fukiage, in New York City. Originally from Yakima, Washington, Mitsue met Toge while studying at University of Washington. Over one hundred people attended the wedding, conducted by Rev. Alfred Akamatsu. Nisei singer Mariko Mukai served as maid of honor and performed two songs. The couple would have two children, Donald and Kay.

Due to his residence in New York, Fujihira escaped the mass incarceration of the West Coast Japanese American community following Executive Order 9066. He joined in community assistance efforts, notably the creation of the report, “A Social Study of the Japanese Population of Greater New York Area” sponsored by the New York Church Committee for Japanese Americans. Fujihira chaired the survey’s Distributing and Collecting Division. In June 1942 Fujihira reported to the Pacific Citizen on a conference in New York of the Japanese Young People's Christian Federation.

As the war went on, Fujihira increased his community involvement, taking work with the War Relocation Authority to help resettle former incarcerees in New York. Among the newcomers was his brother Tod Fujihira, who was also a photographer. Meanwhile, Toge helped organize and coach a basketball team of resettlers, representing the Japanese American Young People’s Christian Federation of New York. In 1944 the team won in a tournament in an 8-team interracial league sponsored by the Church of All Nations.

Toge also worked as a photographer for the WRA, documenting the arrival and activities of Japanese Americans in the city. As part of his assignment, Fujihira photographed the likes of Miné Okubo and Mitsu and Taro Yashima. These photographs of New Yorkers further advanced his photography career. After the end of the war, Fujihira reduced his involvement in community affairs, though he continued for several years to contribute photographs to Japanese American journals such as the Pacific Citizen and New York Nichibei and the magazine Scene.

At some point during World War II, Fujihira was hired as a staff photographer by the United Methodist Church’s Board of Missions (according to legend, he initially was hired by the board for its shipping department, until its members discovered his talent with a camera, where upon he was shifted to the photographer’s job). He would remain with the board, later renamed the Board of Global Ministries of the United Methodist Church, for some 30 years.

Fujihira’s work with a camera soon attracted the attention of documentary filmmaker Alan Shilin, a decorated US Marine Corps captain and former Hollywood writer for Republic films. Fujihira and Shilin worked together throughout the postwar years, embarking on a productive partnership that documented varied peoples throughout the world. The first film on which the two collaborated was The Great Spirit of the Plains, filmed in 1947 and produced by the Methodist Board of Missions. The film told the story of an annual church conference which brought together members of different Native American groups in Oklahoma. It featured native dances and ceremonies, as well as depiction of arts and crafts and the role of sports and education in the lives of the “Oklahoma Indians.”

Perhaps Shilin and Fujihira’s most celebrated partnership was in the production of a series of half-hour documentaries on Native American groups throughout the United States, which Shilin wrote and directed and for which Fujihira provided the cinematography. The ten films of the series were directed by Shilin and filmed by Fujihira on behalf of the P. Lolliard Company, as part of an advertising campaign for Old Gold cigarettes. With permission and support of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and National Park Service, Shilin and Fujihira visited numerous Native American reservations and national parks to document Native American culture and the surrounding environment in places such as the Great Plains and the Florida Everglades. Each film began with a placard for Old Gold cigarettes and a message of gratitude “to the people who gave tobacco to the world.”

The first Shilin-Fujihara film to be produced in this series was their 1949 production on the Seminoles. Titled Seminoles of the Everglades, the film was one of the first to profile the Seminoles, following the experiences of one Seminole man and his plight. Critics noted Fujihira’s emphasis on nature, the diversity of wildlife in the Everglades, and the poverty facing the Seminoles living in the shadow of nearby Miami’s wealth. The film was later entered into the Venice International Film Festival. Fujihira’s work on the film was profiled by the Pacific Citizen. He explained proudly that the Seminoles tended to be suspicious of white men, but that they had readily accepted him, though he was likely the first Nisei they had ever met. He added that the Native Americans he met in both Florida and Oklahoma faced “problems of color and ancestry” similar to those encountered by Nisei and other American racial minorities.

In 1950, Shilin and Fujihira filmed The History of the Pueblo and Hopi Indian People, which presented itself as the first official film of the Hopi people. The History of the Pueblo and Hopi Indian People documented life on the Hopi reservation and Hopi farming culture, with particular attention given to the ceremonies of the Hopi. Fujihira also provided photography for a similar film, titled The Pueblo Heritage, in 1950. The film opens with images of the ancient city of Mesa Verde, and documents the history of the Pueblo people and their lives in the high Colorado desert. Part of the film also celebrated the work of the Office of Indian Affairs in providing schools and equipment that allowed Pueblo artists to adapt to contemporary tastes.

Other films soon followed. Miracle on the Mesa, released in 1950, shows extant Hopi villages in the Arizona desert and points out the need of the Hopi people for a water conservation program. The film was well-received, and earned a prize as best commercially-produced picture at the Cleveland Film Festival. The Rivers Still Flow told the story of Howard Red Bird, a Cherokee who goes off to Bacone College for Indians in Muskogee, Oklahoma. While it references the Trail of Tears and the historic injustices done to the Cherokee, it emphasizes the value of Christian conversion and assimilation.

Shilin and Fujihira’s 1951 film on Native Americans, Fallen Eagle, profiles the Sioux. As with previous films, Fallen Eagle both explores Sioux culture and extolls the work of the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs to “better” the lives of the Sioux through agricultural projects and building hospitals. At the end of the film, the narrator proposes that the Sioux, along with the American government, industrialize the Missouri River into a manufacturing zone. In 1953, Shilin and Fujihira produced the last of their series, Giant of the North, a film on Alaska. In contrast to the previous films, Giant of the North focuses also on the wildlife of Alaska and on the then-territory’s development by the United States as a bastion against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The second part of the film profiles the Point Hope Inuits, detailing their lives on the edge of Alaska and the importance of whaling to their culture. The last part of the film documents the presence of the U.S. Air Force in Alaska, following the work of jet pilots on an unidentified airbase. The film was awarded first prize at the Kentuckiana Film Festival.

The Shilin-Fujihira films were produced for a largely white viewing audience. Although the filmmakers tried to offer some voice to their Indigenous subjects, the films also reflected the official interests and sometimes paternalistic attitudes of the Bureau of Indian Affairs—ironically, the films were produced in large part during the period when Dillon Myer, the former director of the WRA, was the director of the Indian Bureau. Although critics praised the films for their attention to detail and lovely cinematography, some also derided them for their overt commercialism on behalf of Old Gold cigarettes. Fujihira’s daughter Kay later recalled that, as a kid, she was horrified when her elementary school screened her father's films and some of her white classmates, accustomed to the stereotyped views of 'cowboys and Indians' depicted in Western shows of the 1950s, mocked the films and the Native Americans whose lives they portrayed.

© 2021 Greg Robinson; Jonathan van Harmelen