“Why should we care today about events that happened nearly eighty years ago? We should care because there are those today who cite the Japanese American incarceration as ‘precedent’ for “rounding up” others on the basis of race, national origin, and religion, for no justifiable reason. We should care when our government acts in unconstitutional ways.”

— When Can We Go Back to America?, p.xxii

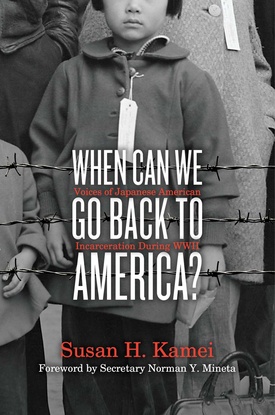

Professor Susan H. Kamei first began pulling together materials for a course called “War, Race, and the Constitution” incarceration at the University of Southern California (USC) in 2017. Those materials, which aimed to immerse undergraduates in the history of the WWII Japanese American incarceration soon transformed into a draft of her recent book, When Can We Go Back to America?: Voices of Japanese American Incarceration during World War II. (2021) Prof. Kamei will host a virtual discussion of her book on Saturday, September 25 from 2 p.m.–3:30 p.m. PDT.

When Can We Go Back to America? finds a unique space in the extensive literature on the Japanese American incarceration, by placing the experience within a broader context of anti-Japanese discrimination—rather than as an isolated event that occurred in reaction to the Pearl Harbor bombing. In a recent email interview with Discover Nikkei, Prof. Kamei emphasized the criticality of this big-picture perspective.

“As important as it is to share the information about the incarceration itself,” she said, “I thought that needed to be placed in the context of the discrimination that the Issei faced from when they first started to arrive here from Japan and the pre-World War II anti-Japanese climate, through the resettlement period and post-war era, redress, and especially the implications of the incarceration today. It needed to be more than just: Pearl Harbor was bombed, there were camps, and the camps closed.”

And it is no wonder that Kamei has this nuanced perspective to offer, as she herself grew up the sansei daughter and granddaughter of incarcerees, and later went on to play a crucial role in the 1980s redress movement.

Growing up in southern California, Kamei heard occasional reflections from her mother and father about their WWII experience.

“One afternoon when I was in elementary school, I had finished practicing for my upcoming piano lesson,” she recalls in the book introduction. “My mother said to me wistfully, “I wish I still had your aunt’s piano music for you. We had to leave so many things behind when we left for camp.” (pxxi)

This comment was Kamei’s first notion of how incarcerees were forced to leave behind their entire lives when they were forced into the camps and then rebuild from scratch after the war.

And then she remembers the “look of resolve on my father’s face. . . when he told me that on the night of December 7, 1941, the day of the Pearl Harbor bombing, two FBI agents searched my grandparents’ home without a search warrant.” (pxxii)

Her father later became active within the Japanese American community and encouraged her to study law, to protect those who were similarly victimized and unable to access resources they need to rebuild their lives. She did exactly that, and while still a law student at Georgetown University, she began assisting with the redress movement (the movement to acknowledge wrongdoing and to compensate camp survivors) in 1979-80. Post-graduation, she returned to the Los Angeles area and, alongside her father, became a key figure in local organizing to support the redress bill.

Both she and her father were among those invited to witness President Reagan’s signing ceremony of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which included an official government recognition of the “grave injustice” done to Japanese Americans, and mandated a payment of $20,000 to every surviving incarceree. When asked about this momentous event, Kamei soberly shared that “I remain very honored that I was included in the guest list to witness President Reagan’s signing ceremony. And yet as thrilling as it was, there was a lot that was also bittersweet about the day, as I think we were all thinking about those who didn’t live to see that day.”

Aside from its broad historical perspective, a second unique feature of Kamei’s book is its copious use of firsthand narratives to tell the story. The book’s 360+ pages of narrative are peppered with hundreds of first-person anecdotes from Japanese Americans, young and old, reacting and declaring, laughing and crying about events in the moment, as they experienced them.

I asked the reason for this unique format, and Kamei, an experienced educator, shared that the value was both the color and the realism that these voices bring to such important history. “The voices. . . were ways to make the history come alive. . . and highlighting different voices to share perspectives at various points of time also was a way to show that there was not one monolithic way that the incarcerees faced and handled the incarceration experience and its aftermath,”she said.

At the end of the book, she reemphasizes the importance of firsthand accounts by dedicating 162 pages to short biographies of each incarceree whom she had quoted in the main part of the book, paying tribute to their lives and stories in a way that serves as an invaluable learning materials for future students and readers.

Below is one firsthand narrative that remained with me from the book, among many, many others: In 1987, House Representative Norman Mineta stood before his colleagues in Congress as one of many former incarcerees who were speaking out in favor of redress:

“My father was not a traitor. He came to this country in 1902 and he loved this country…My mother was not a secret agent. She kept house and raised her children to be what she was, a loyal American. Who amongst us was the security risk? Was it my sister Aya, or perhaps Etsu, or Helen? Or maybe I was the one, a boy of 10½ who this powerful nation [thought] was so dangerous I needed to be locked up without a trial, kept behind barbed wire, and guarded by troops in high guard towers armed with machine guns.”

—The Honorable Norman “Norm” Yoshio Mineta, 1987

When Can We Go Back to America? was published on September 7, 2021 by Simon & Schuster. The book is available in the JANM Store. Register to attend Professor Kamei’s virtual book discussion on Saturday, September 25, 2021, from 2 p.m.–3:30 p.m. PDT. She will be joined in conversation by William A. Darity Jr, Samuel DuBois Cook Distinguished Professor of Public Policy at Duke University, and A. Kirsten Mullen, writer, folklorist, museum consultant and lecturer, co-authors of From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century. The event is $10 for general admission and free to JANM and JACL members. RSVP here.

© 2021 Kimiko Medlock