Brazil, which currently boasts the world's largest Japanese community at 2 million, also began with 250,000 Japanese immigrants, about 50,000 of whom were postwar immigrants.

The biggest characteristic of the postwar generation is that there are many "war veterans" and "former Manchurian immigrants or people born in Manchuria." There have been no surveys, so the actual numbers are unknown, but this is my impression from 25 years as a Japanese newspaper reporter. Half of the postwar immigrants returned to Japan within a few years, but I think that of those who remained, about one-quarter to one-third were people who experienced Manchuria.

After returning from Manchuria to the mainland, they lived there for a while, but based on their experiences living on the continent, they felt a desire to go abroad again due to the cramped, restrictive, and severe food shortages on Japanese soil, and it is thought that many of them flocked to Brazil, which was one of the few countries at the time that had resumed immigration.

For this reason, many of the autobiographies written by immigrants are about their wartime experiences, such as the autobiography "Kougen," which won the Colonia Literary Award, a literary prize for the Japanese community, in 2005.

The author, Nozawa Kesayuki (deceased), writes in simple, matter-of-fact language about his turbulent life, including the harsh pioneer life in northern Manchuria where he spent his childhood, the deaths of his family, the misfortunes that continued after he returned to Japan after the war, his life after coming to Brazil as a young man from Kochia in 1957, and his time as a dekasegi worker.

The Nikkei Shimbun also reprinted the entire article in 2007, where it was well received. In a reporter's column at the time, Kanda Daimin, the editor at the time, introduced the following comments from readers: "The 82-year-old former army officer had requested Nozawa's address, saying that he would like to send a condolence gift and offer incense. Sixty-two years have passed since the tragedy in Manchuria. It turns out that his older brother worked for the former South Manchuria Railway and suffered the same fate as Nozawa's family and relatives, so it is something that cannot be someone else's. He said that he cannot read it every day without crying, and he cried while speaking with the author. His voice became choked up and it was difficult to hear what he was saying. For this man, Manchuria has not yet faded away. He was deeply moved when he read Nozawa's writing."

Relocation to the Amazon was no big deal for Siberian prisoners

Noriyuki Taniguchi (deceased, from Hiroshima Prefecture), who immigrated with his family to the Guama Federal Settlement Area in the state of Pará as Amazonian immigrants in 1957, left behind an autobiography, My Siberian Prisoner's Record, in 2009, at the end of his life, in which he wrote about his brutal wartime and postwar experiences. It is a record of the tragic experiences of postwar immigrants, including the dispatch of soldiers to Manchuria and their Siberian internment.

Six months before the end of the war, he enlisted in the 119th Division Infantry Regiment's machine gun company and headed for the northwestern part of Manchukuo. While he was working on building a fort in Irecute, the Soviet army invaded, and he witnessed hell: "In just four days of fighting, half of the regiment was reduced."

On August 18, he was detained by the Russian army, and was crammed into a freight train overnight like livestock and taken to a camp (gulag). "When I woke up for roll call in the morning and went outside, I couldn't breathe. The air was so cold." He was forced to move without food and was forced to work. When he swung his pickaxe down on the ground, it bounced back with a high-pitched clang. The ground was completely frozen.

When he arrived at Sasebo, Nagasaki Prefecture, in January 1947 after his internment, his weight had dropped to 40kg, down from 58kg at the time of enlistment. "During my internment I wandered on the brink of starvation, endured extreme cold where even sound was freezing, endured forced labor, and was tormented by a burning longing for home," he wrote about his experiences at the time.

In May 1957, 10 years after his return from Siberian internment, he and his wife's family settled in the Guama Federal Settlement Area in the state of Pará. The reception facilities at the time of settlement were completely undeveloped, and the settlement was in such a terrible state that farmland was flooded during the rainy season, so many of the settlers fled in the middle of the night. However, Taniguchi laughed and said, "It was nothing compared to Siberia."

When he returned from Manchuria, half of the people in his hometown had died in the war.

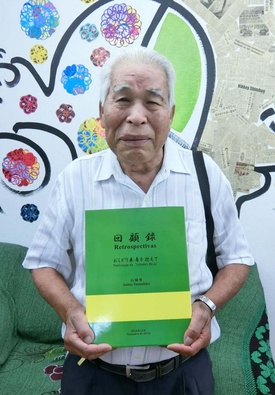

Isamu Yamashiro, a postwar immigrant who has served as president of the Okinawans in Brazil Association and chairman of the Okinawa Cultural Center, published his autobiography, "Memoirs: Celebrating My 88th Birthday," in 2017.

Born in Komesu, Itoman City in 1928, Yamashiro enlisted in the Manchuria-Mongolia Development Youth Volunteer Corps in 1943 and traveled to Manchuria. After living as a refugee in Dalian for two years after the war, he returned home and traveled to Brazil in 1958 as part of the 4th Okinawa Industrial Development Youth Corps.

Yamashiro was 16 years old when the war ended in Manchuria. He vividly describes how, immediately after the Emperor's radio broadcast, "I witnessed several senior officers of the volunteer army cutting down all the pigs kept in their units with military swords. Looking more closely, I saw the pigs running around the square, bleeding and dragging their half-decapitated heads. The half-dead pigs were bumping into each other here and there. I understood that this was a way for the soldiers to release their frustration, but it seemed just too cruel" (page 118).

He continued to live as a refugee in Dalian for nearly two years, and was finally able to return in 1947. "I returned to Sasebo, Nagasaki, thinking that my family had been wiped out in the brutal ground battle in my hometown of Okinawa. In my heart, there was no point in returning to Okinawa, where my family had been wiped out in the suicide attack by the prefectural people, so I decided to go to Hokkaido and waited in an internment camp. At that time, I happened to meet my mentor, Yamashiro Kokichi, who informed me that my family was still alive. I suddenly changed direction and returned to my hometown of Komesu" (greetings).

His father and brother were killed in the war, but the other seven narrowly escaped death, and they were reunited for the first time in four years. Yonezu is a district that stretches from where the Himeyuri Monument stands to the coast, and is located at the southernmost tip of Okinawa Island. It is the district where the ground battle was decided, and is the district that suffered the most damage. According to Yamashiro, 62 of the 250 families in the district were wiped out. In terms of population, 648 people, more than half of the 1,252 people, died in the war.

Even after the war, Okinawa continued to be occupied by the US military, and "the prefecture's residents were confined and trampled under military boots, and the island had no industry, so food and jobs were scarce. Furthermore, there were many people returning from overseas, and the natural population increase was 20,000 people per year, which became a major social problem" (greetings).

Many of these repatriates once again aimed for overseas. "When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the occupying forces began forcibly requisitioning farmland everywhere to expand their military bases. The people of Okinawa were terrified that Okinawa would once again be drawn into war. This rekindled the desire to go overseas in search of a peaceful and better life" (ibid.), which is how they emigrated to Brazil.

"You can't move an island, but you can emigrate people."

I was shocked when I read the draft autobiography of postwar immigrant Sonoko Akamine. It began with a scene during the Battle of Okinawa, in which she was covered in blood and asked her father, "Am I going to die now?"

A typical autobiography begins with a description of when and where one was born, followed by fond, heartwarming memories from one's childhood. However, hers does not have any nostalgic nuances. It is as if she has no warm memories of her childhood. The first page of her life begins with a harsh description of the Battle of Okinawa.

Nishihara Village, where she was born, is located on the opposite side of Naha City in the center of Okinawa Island, and is one of the places where the US military fought fierce battles. As a result, five members of her family became the noble victims, and she herself, who was a small child at the time, was bombed and burned, even though she was in a shelter in the mountains. The words she asked at that time were the questions at the beginning of this article.

This experience was traumatic and determined the course of her life and that of her family. When asked why she emigrated, she answered, "Islands cannot be moved, but people can emigrate." There were many people who thought the same way, which is probably why so many people emigrated from Okinawa after the war.

Hearing that his uncle, who had gone to Brazil before the war, was living a good life, he decided to go to Brazil, a country without war. After that, he begged his parents to let him go to Brazil whenever he had the chance, but they would not listen. In the end, he begged them and moved with his family.

They headed to South America, driven by the fear that "what if we get caught up in another war..." The people who remained in Okinawa bring up the base issue at every opportunity because they "want to distance themselves from war as much as possible." Behind both immigration and the base issue lies a trauma that goes beyond reason.

His daily actions are based on gratitude for having survived the ground battle and the belief that "it is thanks to my ancestors that I am alive today."

Whenever Sonoko had to make important decisions in life, "war" was always on one side of the scale. If she had to weigh "war" against "hardships in a foreign country," the latter would have won. In other words, she would not mind moving to a foreign country with a different nationality, culture, and language if it meant she could live in peace.

Perhaps because he was the one who brought his family to Brazil, he worked himself to the bone to serve them. He faced every difficulty with a positive attitude and used all his wisdom to solve them. By facing difficulties, he was able to unleash his hidden talents that he would not have been able to develop if he had stayed in Japan, and carved out a life for himself in Brazil.

Although 76 years have passed since the end of the war, 70% of the US military bases in Japan are still concentrated in Okinawa Prefecture. This fact shows that the "tension situation" has not changed. If North Korea launches a nuclear missile or the People's Liberation Army of China attacks, Okinawa will be the first target, and there is no denying the possibility that it may one day become a battlefield again.

That is why it is important for them to increase the number of their descendants in a war-free Brazil. The Okinawans are already laying the groundwork for emergencies.

His autobiography describes true stories of how families are connected by invisible threads, such as when his father passed away and his younger brother, who he had not been able to contact, suddenly returned home just before the funeral procession. "Even if the language and culture change when we move to a new place, it is not a big problem. As long as the family bond remains the same," he says. This conviction is evident between the lines. Leaving descendants behind, no matter what. That is the cherished wish of the Okinawans who inherited life from their ancestors.

* * * * *

Watching Brazil's postwar immigrants, I am keenly aware that the essence of "migration" is for citizens to take the attributes of their homeland, whether it be Okinawa or mainland Japan, which are beyond the control of individuals, and use them to create positive effects in their lives by going through the process of "crossing borders."

© 2021 Masayuki Fukasawa