The Mexican authorities ordered all families of Japanese origin to immediately move to the cities of Guadalajara and Mexico with the purpose of being concentrated and closely monitored. Without understanding why he had to leave his home, abandon his school and get away from his friends, René headed to Guadalajara in the company of his parents in the first days of January 1942.

The concentration order represented for René Tanaka not only a change of place of residence. The first months of that year in the city of Guadalajara and later in Mexico City, where he lives until now, actually meant a total transformation of the life to which he was accustomed in the town of Ures, a stage that he remembers as the most happy of its existence.

One of the things that René began to miss was the pet that one of the chickens that his mother raised in the yard of their house had become. The chicken was special to René because of the blue of its plumage, a color that stood out when in contact with the sun's rays. His father Zenzo had built him a small wooden cart in which he walked the “blue hen” as she would be known throughout the neighborhood.

René also missed the huge patio of his house where, in addition to the chicken coop, a leafy date palm tree never stopped producing the fruit with which his mother prepared a delicious jam that he would never eat again. Under the shade of the palm tree, his father had built a kind of bathtub that resembled the furo or tub bath in which the Japanese usually immerse themselves to relax from their daily work. Using an oil tank cut lengthwise, Zenzo placed it on a base containing firewood to heat the water. At the bottom of the tank, he had adapted a wooden grate so that the body could rest peacefully.

The culture of the town of Ures and its geographical environment provided René with identity elements that forever marked his life and memories as a child. The walks through the mountains that cross Sonora allowed him to meet deer and pumas. The trips to the river during the hot summer made him enjoy the cool, crystalline water that comes down from the mountains into which he would dive while hugging a watermelon that kept him afloat.

The great diversity of stews and meals that were prepared in the region continued to be part of the memories that accompany it to this day. The so-called Menudo or stew made with the belly, legs and intestines of beef, seasoned in a broth with corn grains and the chiltepin chili from the region, became one of the favorite dishes of the Tanaka family. But René's mother also learned to cook corn dough tamales made with meat and lard wrapped in corn husks, which became René's favorite dish.

As is known, flour tortillas are a fundamental part of the culinary culture of northern Mexico, particularly those that reach a diameter of up to 50 centimeters and that accompany the Sonoran food to which the Tanakas and a group of immigrants who settled in Ures they were introducing them into their daily diet.

The Tanaka family not only learned to value this culture as their own but used it as a means to survive. Zenzo set up a food stand in the main square of Ures where he sold “lonches” as the word lunch had been Spanishized in English. Burritos , as flour tortillas filled with beans or dried ground beef are called, were one of the foods that sold the most at the Tanaka stand.

Another of the products that Zenzo sold with great success were ice cream and shaved ice. Both René and his mother participated in their preparation. Milk ice creams with walnut, vanilla, chocolate or strawberry flavors were prepared in a metal bucket that was placed in a wooden tray covered with ice and salt. To harden the flavored liquids, it was necessary to rotate the container continuously for dozens of minutes until it had the consistency of ice cream. Given the successful sale of ice cream, Zenzo adapted a small motor so that the rotation of the ice cream container was not done manually.

The preparation of the shaved ice also required the participation of all members of the Tanaka family. Zenzo and René were in charge of going to buy the enormous pieces of ice in the city of Hermosillo in a truck that the family bought. Transporting the ice was not easy as it was covered in sawdust and wrapped in blankets to prevent it from melting during transport. At home, Zenzo stored the pieces in a special room where he would cut them throughout the week as needed. At the stall in the town square the shaved ice was sweetened with strawberry, tamarind and currant jams according to the customer's taste. It is noteworthy that the peach jam was acquiring its Japanese touch as customers requested their momo shaved ices referring to that fruit with its name in Japanese.

Another candy that the Tanaka family began to make was dulce de leche sweetened with sugar to which pine nuts or walnuts were added. In large copper saucepans the milk was heated and when it boiled it did not stop moving until it caramelized. This sweet, known as jamoncillo, is very popular today as it is part of the traditional sweets of Sonora and other places.

The relationship of this family with the local population in social, economic and emotional terms is an example that shows the insertion of Japanese communities in a town like Ures and the complex symbiosis in which a Japanese culture was forged in Mexico that It is known by the generic name of Nikkei , a concept that would need to be explained in greater detail.

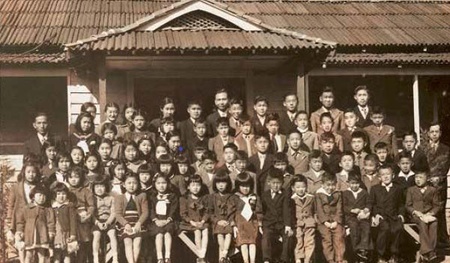

When the war broke out, the breaking of the close ties of these communities with their environment throughout Mexico meant an unfortunate time for the thousands of immigrants who were fully integrated into the towns and cities where they lived. For René in particular, the move to Mexico City in the Tlalpan neighborhood constituted a type of emigration like the one his parents had experienced. Along with eight other Japanese families who came from different places in Mexico and who had been forced to concentrate, René had the opportunity to collectively delve into the Japanese culture of his parents. In Tlalpan, the immigrants set up a school where children learned to speak and write Japanese fluently. The teacher, who was paid by the parents, was one of the central pieces so that children born in Mexico were educated as they were in Japan, even with the textbooks that were used in that country and in which It highlighted as a central element the respect and indoctrination of the figure of the emperor, a symbol of the unity of the Japanese people.

The difficulties that the Tanakas faced in this new immigration process were compensated by solidarity and the way in which those concentrated collectively resolved the problems. In this sense, the concentration of dispersed communities strengthened ties with the distant Japan from which they came and which the war and the breakdown of communications made more distant and ethereal.

But if the war and the concentration allowed the dispersed communities to establish close ties, its end deeply divided the families that had settled in Tlalpan. When the news of Japan's surrender spread on August 15, 1945, the Japanese communities in all the countries of America faced enormous pain when they did not know the situation of their parents or even their children who lived there as it was. case of the Tanaka family.

The confusion generated by Japan's defeat was reflected in the fact that many immigrants considered that the information about the destruction of Japan was completely false or part of American propaganda, while others accepted the sad reality. This was the case of the parents of the Tlalpan school who divided the community in two: those who considered that Japan had won the war, kachigumi , and the losers, makegumi . The group of “winners” moved to another part of the city so the “losers” could no longer support the expenses of the school, which had to be closed permanently in this neighborhood.

The end of the war opened a new stage for immigrant communities that completely rejected returning to their country or even no longer considered it convenient to move to the places where they had previously lived. The Tanakas, like the vast majority of those concentrated in the cities of Mexico and Guadalajara, took advantage of the possibilities that these cities offered them to educate their children. The training of children became the central concern of the concentrates. The vast majority of these children entered public universities over time where they trained in different professions. René is one of them, as a dentist he has contributed to the prestige enjoyed by this broad guild of professionals of Japanese origin.

© 2021 Sergio Hernández Galindo