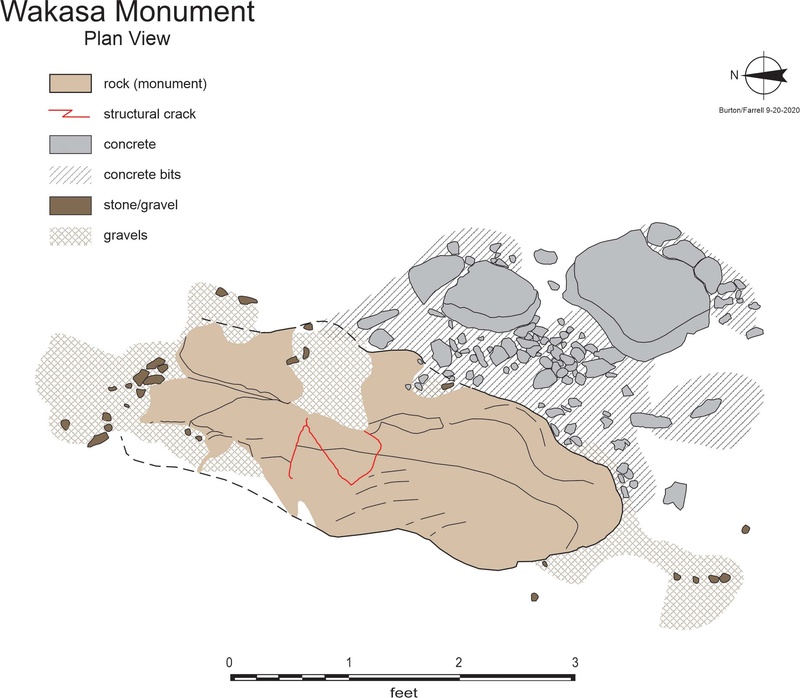

The monument stone, toppled, perhaps face-down in the dirt, is a witness to the honor fellow incarcerees tried to show Mr. Wakasa. It is also a witness to the administration’s effort to eradicate that honor and suppress the truth of the killing. For the stone to tell its story, it needs to be carefully examined by gently lifting it by its side to keep any cracks from spreading, to see if there are traces of writing or other markings on the side facing down.

In addition, the top few inches of soil in the area surrounding the stone could be archaeologically excavated or probed to determine if there are buried rocks or concrete that once supported the memorial stone, and how they were placed. This work may also reveal if any mementos or artifacts that were placed in his memory lie just below the surface.

With the results of the limited excavation in hand, the Topaz Museum Board could consult the local and descendent communities. Is it time to resurrect or re-erect the monument onsite, or protect it in the museum? Should the location where Mr. Wakasa died be memorized with the original rock or a replica? Should there be an interpretive sign at the side of the road to help honor Mr. Wakasa’s memory, and the memory of all who were unjustly imprisoned at Topaz?

Could the sign convey the intimidation that must have been caused by this example of lethal violence against someone who ventured too close to the fence? Should the stone be left as it is, as the camp administration decreed, to be forgotten? Or should it be rebuilt as the incarcerees made it? If there is writing on the stone and it is restored, should the monument stone’s flat surface face east, as it most likely was when it was constructed so it could be seen by those inside the fence? Or should it be turned to the west, so visitors outside the fence can see the inscription from the road?

The potential for vandalism need not be a deterrent to interpretation. If the threat of vandalism is too great to reset the original stone, a cast could be made, which would be easily replaceable. The potential for vandalism could also be reduced by involving the local community in the restoration project: materials needed for its restoration could be purchased locally or donated; rocks needed could be gathered by a local service group; the high school could be involved in planning the dedication or unveiling. If the stone needs to be moved to storage, the Delta volunteer fire department may be able to help move it with their stretchers, blankets, and strength. The local community and the descendant community could work together in the reconstruction.

The Topaz site is in better condition today than it was 25 years ago, when we first visited it, with a parking area and flagpole at a well-maintained interpretive display and the new sign commemorating Mr. Wakasa’s death. The vandalized plaques we saw in 1995 have been replaced.

A few of the important elements related to Mr. Wakasa’s monument would benefit from monitoring, stabilization, and preservation. For example, the historic security fence is in disrepair, with barbed wire strands loose, broken, and missing, and some posts askew. The fence may be able to convey its history better if it is repaired, though the top strand of barbed wire may need to be lowered to facilitate the passage of pronghorns and site visitors who want to see the monument close up. Depending upon the communities’ recommendations, an opening in the fence and a hardened trail could facilitate visits, or the fence could be strengthened to keep people away.

The tree memorial to Wakasa, of unknown age and origin, is leaning precipitously, and stabilization and repair of the base will be needed to preserve it in place. If it is impossible to repair, it could be conserved at the Topaz Museum. The sign placed in 2015 could be moved closer to the site of the killing.

Further afield, the building in downtown San Francisco where Mr. Wakasa lived just prior to the Relocation is still standing. Here a small marker, placed flush in the sidewalk, could memorialize Mr. Wakasa and the incarceration, and lead people to search out further information. Over 70,000 similar markers have been placed in more than 1,200 cities and towns across Europe at the former homes of Holocaust victims.1 Similar to those, the marker could read:

Here lived

James Hatsuaki Wakasa

Born February 24, 1880

Killed by Military Police

April 11, 1943

Topaz, Utah

Because of the efforts of the Topaz Museum Board, the town of Delta, and the Topaz inmates and their descendants in preserving the Topaz site, Mr. Wakasa, the monument to his killing, and the significance of his death will not be forgotten.

* * * * *

The authors thank Nancy Ukai for sharing her information with us, which allowed the remnants of Waskasa’s monument to be found and documented. We also thank Jane Beckwith and two anonymous Topaz Museum Board members for their comments and suggestions.

Notes:

1. Eliza Apperly, ‘Stumbling stones’: a different vision of Holocaust remembrance. The Guardian (February 18, 2019).

*Editor’s note: Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. The following article does not represent the views of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei publishes these stories as a way to share different perspectives expressed within the community.

© 2020 Mary M. Farrell; Jeff Burton