1943–1946: While Walking his Dog

How is such a tragic event noted when it occurs? What memories are taken away? By the time Topaz closed in October 1945, Wakasa’s shooting had been documented in various ways beyond the government memos and press releases.

Memories of the children appear to be benign. Lillian Yamauchi and her third-grade classes kept a diary at Topaz. The entry for April 14, 1943, states: “On Sunday evening at 7:30 o’clock, an old man, Mr. James H. Wakasa passed away.” An April 20, 1943, entry simply notes: “yesterday was Mr. Wakasa’s funeral.” Even young children were aware of the event, but perhaps not of its ramifications; possibly the teacher was fearful of official condemnation and ensured that the diary entries would not offend the administration.1

In a collection of 57 remembrances by the Topaz High School Class of 1945, most share quintessential American high school memories, and only two mention a shooting. Yasumitsu Furuya writes that he did not know anyone was shot at the time but read about it later.2 Somao Ochi writes “One had to be very careful not to stray too close to the fence for they were apt to have itchy trigger fingers. In Topaz, one such elderly stroller was shot to death by a guard”.3 A questionnaire sent to Topaz survivors in 1989 elicited other personal memories of the shooting and Wakasa’s dog:4

Miyoko Nakagawa recalled that her parents thought the dog was a stray. “My mother and father said he had a dog and always took him for a stroll around the fence. Since he was in Block 36, the desert was very appropriate for his dog to walk around.”

David Kitagawa wrote that Wakasa “was careful not to let his dog run around loose or bother others… He was not trying to escape. There was no need to shoot him.”

The shooting is also memorialized in art. Chiura Obata documented his confinement at Topaz in paintings and letters. A Professor of Art at the University of California Berkeley before he was incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz, he started an art school at both incarceration sites. Obata was in the Topaz hospital recovering from an attack when the killing took place but created a sumi ink painting based on the accounts of Topaz residents.

Mr. Wakasa is depicted in mid-fall, doubled over with hands outstretched. A dog looks on, its mouth and posture expressing alarm and horror. Although the painting is simple, small details are evocative: Mr. Wakasa is well dressed and facing the guard tower (which is well out of the frame) rather than the fence; the land beyond the fence is empty save for brush and distant hills.5 Neither the identity nor the motive of the person who attacked Obata was ever identified, but for his own protection Obata was removed from Topaz May 18, 1943, and his family soon followed. The painting of the shooting is now in the collection of the National Museum of American History. Although it is not on display physically, it can be viewed online.

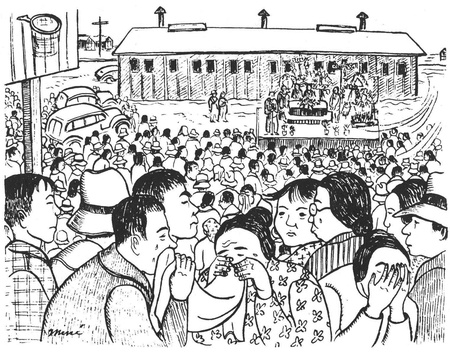

Miné Okubo left Topaz January 19, 1944, for a job with Fortune magazine in New York City. At Topaz she helped found a literary review, Trek, and taught art to children. She documented the incarceration in over 2,000 drawings and paintings. First published in 1946, her book Citizen 13660 was the first personal account of the Japanese American incarceration to be published. Of the nearly 200 drawings in her book, two of them and a brief text chronicle the shooting. One is of the funeral and one shows women making paper flowers.

1982–1994: Reclaiming History

In 1982 Delta High School teacher Jane Beckwith assigned her journalism class the task of researching and writing about the Japanese American incarceration at Topaz. “The assignment lit a fire,” writes James Sloan Allen.6 With the help of her students, in 1989 Beckwith created an exhibit within the Great Basin Museum in Delta. Half of an original Topaz recreation hall was donated, and planning began for the Topaz Museum. “The restored recreation hall was dedicated in 1994 during a ceremony that included former Topaz internees, former Topaz administrative employees, and local Delta residents”.7

The Topaz Museum Board incorporated as a non-profit, intending to buy as much of the Topaz site as possible, and to have the former incarceration site recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

1995: Confinement and Ethnicity

Twenty-six years ago, we wandered that same desert to see what might be left of the camp. Congress had acknowledged the injustice of the mass incarceration and created a National Historic Site at Manzanar, one of the ten Relocation Centers. The first superintendent of Manzanar, Ross Hopkins, provided funding for an archaeological assessment of other sites where Japanese Americans were confined because of their ethnicity. Topaz is particularly important, and particularly haunting, because of the killing of Mr. Wakasa and other documented shootings.

We noted that most of the footings for the guard towers had been pulled out of place but remained near where they were originally. Three of the other guard tower footings remained in place. The security fence was still in place around much of the site with the four original strands of barbed wire. An extensive landfill outside of the fence includes institutional and Japanese ceramics. In the former residential area, we documented concrete slabs from the latrines, laundries, and mess halls. Dead and dying trees dot the landscape. There are paved roads, gravel paths, and remnants of landscaping, including ornamental gardens and small ponds. Artifacts littered the ground, and we noted remnants of baseball field backstops. About 3 miles away in an abandoned building once used as a kitchen for farm workers are names, dates, and hometowns, testimonies to loss and longing.8 A large historical monument erected in 1976 by the Japanese American Citizen League chapters in Salt Lake City had been defaced by bullet holes. On one plaque, the image of a little girl had been shot.

2001: Site Documentation

Twenty years ago, a lone archaeologist walked the Utah desert. Hired by the Topaz Museum Board through a Save America’s Treasures grant, Sherri Murry Ellis had been tasked with surveying the 417 acres of the Topaz site then owned by the board.

Ellis recorded a wealth of features and artifacts: a child’s toy truck, a pocketknife, a baby buggy, inscriptions in concrete, and many other remnants of past lives. In the area between the residential housing and the security fence she found much of the space devoid of features, but recorded ditches, concentrations of structural debris, coal, and gravel, remains of the sewer pump station, and a few concrete foundations.

Ellis also recorded a monument, at what from a distance appears to be a tall tree stump:

The Wakasa monument, located southeast of the former central guard tower along the western perimeter fence, consists of a low earthen mound with an upright tree trunk with the name “WAKASA” carved into it. Mr. Ron Walkshorse, who lives in a house on former Block 35, has used white paint to paint in the carved letters and has added the words “IN MEMORY” to the marker.

It is unclear whether the marker and the carving in it are original to the camp, being installed by fellow internees shortly after the shooting, or whether it was created by Mr. Walkshorse, who has placed a sign on the remains of the sewer pump station noting the location and date of Mr. Wakasa’s death.9

Ellis identified major challenges involved in preserving Topaz, including funding, vandalism and looting, visitor apathy (caused by the disappointment at the lack of things to see), the site’s remote location and harsh environment, and the potential development of private property within the former incarceration camp and in the vicinity. She discussed a range of protection, preservation, and interpretation options. Interpretation could include an on-site visitor center, reconstructed buildings, and a viewing platform. Preservation could include purchase of private lands, repair of the camp roads, and initiation of a site steward program, or a paid security guard or caretaker.

2007–2020: National Recognition

The former Topaz incarceration site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007. Under Jane Beckwith’s leadership, the Topaz Museum Board obtained grants to increase awareness and conduct research into Topaz’s history.6 Construction of a new permanent Topaz Museum on Main Street (U.S. Highway 50/6) in Delta was completed in May 2014, partly funded by the National Park Service through the Japanese American Confinement Sites grant program.

The inaugural exhibition, which opened in January 2015, was a collection of art created and donated by former Topaz inmates.10 The museum includes 3,700 square feet of exhibit space, an auditorium, curatorial storage, and an outdoor exhibit area.

The grand opening for the permanent multi-media museum was in July 2017. The exhibits include a panel on the Wakasa shooting. The Topaz Museum Board acquired six acres of the site in 2020, so the board now owns 639 acres of the 640-acre site. Japanese American Citizen League chapters in the Salt Lake City area own one acre where their monument is located.

Notes:

1. Michael O.Tunnell and George W. Chilcoat, The Children of Topaz: The Story of a Japanese-American Internment Camp, pg. 29. Holiday House, New York, 1996.

2. Darrell Y. Hamamoto, Blossoms in the Desert: Topaz High School Class of 1945, pg.31. Topaz High School Class of 1945, San Francisco, 2003.

3. ibid, pg. 166.

4. Nancy Ukai, Amache Dog Carving: Pets Behind Barbed Wire. 50 Objects/Stories: The American Japanese Incarceration.

5. Kimi Kodani Hill, Chiura Obata’s Topaz Moon: Art of the Internment. Heyday Books, Berkeley, California, 2000.

6. James Sloan Allen, A Town, a Teacher and a Wartime Tragedy. Teaching Tolerance, Southern Poverty Law Center, Montgomery, Alabama, 2011.

7. Topaz Museum, 2020.

8. Jeffery F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of Japanese American Relocation Sites. University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2001. (originally published 1999)

9. Sheri Murray Ellis, Site Documentation and Management Plan for The Topaz Relocation Center, Millard County, Utah, pg. 39. SWCA Environmental Consultants, 2002.

10. Kathy Rong Zhou, Topaz Museum: Remembrance and Tribute, 75 Years On. Slug Mag, June 29, 2017.

*Editor’s note: Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. The following article does not represent the views of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei publishes these stories as a way to share different perspectives expressed within the community.

© 2020 Mary M. Farrell; Jeff Burton