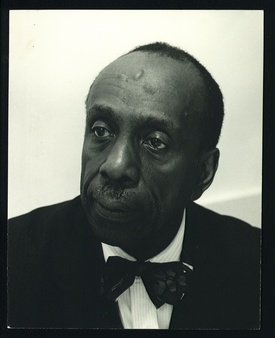

During the early 1940s, Howard Thurman, a noted orator and writer, was dean of chapel and professor of religion at Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington DC. He usually spent his summers on the road, traveling to conference centers, retreats, and churches.

Despite the wartime conditions, the summer of 1942 was no different. That July, his journeys took him as far west as California, where he attended a 10-day Race Relations institute at Whittier College. During that trip, he made it his business to visit an “Assembly Center” for Japanese-Americans, presumably at Santa Anita Park, the thoroughbred race track in Arcadia, California.

As he wrote to a friend: “I saw some of the Japanese internment centers for the Japanese. They are behind eight feet of barbed wire with the outside patrolled day and night with United States soldiers with machine guns. The point that I saw was a former race track and houses about 26,000 Japanese. [That number is probably somewhat high.] The horse stalls have been renovated, but I understand that it still smells horsey.”

Thurman was born in Florida in 1899, and spent his boyhood in Daytona as the vise of Jim Crow was tightening on the state’s Black residents. His was a poor family, headed by his grandmother and mother after his father died when he was eight years old. By dint of his intelligence, ambition, and more than a little luck, he obtained an excellent education, attending the historically Black Morehouse College in Atlanta from 1919 to 1923, and Rochester Theological Seminary in upstate New York from 1923 to 1926. He was ordained a Baptist minister, but denominations did not matter to him. He was a mystic, and thought that the direct experience of God was more important than any religious creed. In the years that followed he became a popular speaker, before both white and Black audiences.

Thurman deserves recognition as the first prominent African American advocate of radical Gandhian non-violence. In 1935 he headed a four-person “Negro Delegation” to India, Ceylon, and Burma, during which time he was one of the first African Americans to meet with Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of the Indian independence movement. He was a longtime member of the prominent Christian pacifist organization, the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). In 1940 he became a national vice-chair of FOR, and would continue in that position during the years of World War II, when it became one of the few national organizations to protest the wartime removal and confinement of Japanese Americans.

Thurman was an opponent of militarism and imperialism of all kinds, including that of Japan. In July 1937, shortly after the commencement of full scale hostilities between Japan and China, Juanita Harris, a Howard University undergraduate, wrote him a letter stating that she supported Japan’s invasion of China because she insisted, if the Japanese didn’t conquer China, “the white man will.” Thurman responded that he completely agreed that “the predominant attitude of the white races towards the darker races” was to “hold the darker races in subjection, if not servitude.” However, he considered Japan to be the aggressor, and added, “I am fundamentally opposed to imperialism, whether the imperialist be black, yellow, white, or any other color.” His pacifism and hatred of imperialism and the subordination of non-white peoples would shape his attitudes toward Japanese American confinement.

Thurman’s summer 1942 visit to the Assembly Center was not his initial encounter with the wartime plight of Japanese Americans. Several weeks earlier, in April 1942, Kenny Murase, a student at the University of California who was active on the executive committee of the local YMCA Race Relations group, wrote Thurman: “The exigencies of an all-out, total war has made it necessary for me, an American-born Japanese, to withdraw from the University of California to enroll in a university in the east.” A friend of Thurman had advised him to apply to Howard University, which, he was told, “would be glad to receive me.”

Murase continued: “It may seem singularly odd that a Japanese student should be interested in attending a college primarily for Negroes, but…belonging personally to a racial minority group presents one concrete basis for my ambitions.” Murase requested a scholarship to attend Howard. Whether because of contradictory instructions from the East Coast Defense Command or fear of the stigma attached to admitting a “Japanese” student, Howard University delayed action on the application and scholarship award, and Murase was forced into confinement at Poston.

In April 1943, Thurman received a letter from Emiko Hinoki, a graduate of Mills College in Oakland, California, who was secretary of the Young People’s Church Council of the Granada Christian Church in the Granada (AKA Amache) camp. Hinoki asked if he could possibly include a stop there during his summer travels, for “you no doubt have a great and inspiring message to give to the minority group such as the Japanese Americans.“

The leaders of the Amache chapter of the FOR also wrote him asking to visit. Thurman responded that “I shall be operating on a very close margin of time, but be assured that if it is the range of human possibility, I shall certainly do this [visit Amache.]” Thurman saw it as a deep obligation to visit the incarcerated Japanese. By May, Thurman had made plans to go from Los Angeles, detour to Amache for a quick stop, and then travel on to Oakland. However, it is unclear if his schedule permitted him to make this stop.

In August 1943, in an article, “The Will to Segregation,” published in Fellowship, the journal of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Thurman wrote, ”the fact that we were attacked by Japan has aggravated greatly the tension between the races. I am not suggesting that the war between Japan and the United States is a race war, but certainly many people have thought of it in terms of a non-white race ‘daring’ to attack a white race. This has given excellent justification for the expression of the prejudices against non-white people just under the surface of the American consciousness,” leading to, on the part of whites, “increasing bitterness, intolerance, and hatred,” and often on the part of Blacks, “reactions in kind.”

Nevertheless, while Thurman remained in Washington, DC, his contacts with Japanese-Americans and with the realities of mass confinement and its consequences remained rather limited. This changed in the summer of 1944, when he moved to San Francisco as co-pastor of the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco, one of the first churches in the United States consciously organized on an interracial and interdenominational basis.

When Thurman arrived in San Francisco he immediately realized he had moved to a center of anti-Japanese racism, as he later wrote: “It was not infrequent that one saw billboard caricatures of the Japanese: grotesque faces, huge buck teeth, large dark-rimmed thick-lensed eyeglasses”. The point was, in effect, “to read the Japanese out of the human race; they were construed as monsters and as such stood in immediate candidacy for destruction. They were so defined as to be placed in a category to which ordinary decent behavior did not apply…It was open season for their potential destruction.”

As was the case in many West Coast cities, it was only during World War II that African Americans moved to San Francisco in large numbers. Blacks lured by opportunities in the defense industry settled into former Japanese neighborhoods, thereby retaining the formal and informal distinctions between white and “non-white neighborhoods.”

The wartime surge in San Francisco’s Black population created a number of social dislocations. The city’s new Black neighborhood rapidly became badly overcrowded. Albert Cleage, who would become the assistant minister to Fellowship Church in early 1944, wrote that “twenty thousand Negroes were crowded into make-shift rooming houses and apartment houses which had accommodated about eight thousand Japanese.”

Joseph James, a founding member of the Fellowship Church who was also a distinguished concert baritone and shipyard worker, wrote in 1945: “Caucasian San Francisco turned the machinery at hand [formal and informal means of discrimination] for the subjugation of the Oriental and applied it to the Negro.” As chairman of San Francisco’s NAACP branch, James would concentrate his efforts on welcoming returning Japanese Americans.

In mid-1944, the San Francisco NAACP passed a resolution drawn up by James “calling for fair treatment of loyal Japanese-Americans and condemning efforts of reactionary interests to incite suspicion among Americans of African ancestry for Americans of Japanese ancestry.” The following year, James joined a delegation that met with state Attorney General Robert Kenny to discuss ways to end violence against Japanese American resettlers.

As Japanese Americans moved back to San Francisco, Thurman found ways to support them. In fall 1944 the Japanese American Citizens League petitioned the West Coast Defense Command for permission to open a San Francisco office, and in October 1944 JACL president Saburo Kido met with the West Coast Defense Commander, General Charles Bonesteel, who authorized the JACL to open its office as soon as the US Army lifted the official exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast.

With Bonesteel’s consent, the JACL meanwhile sent Teiko Ishida, who had been serving as office manager and fundraiser at the wartime JACL offices in Salt Lake City and New York, to San Francisco to prepare. Once Ishida arrived, Howard Thurman offered her a job as a temporary secretary, and she worked with him until January 1945, when the new office formally opened its doors. He declared that Ishida, besides bringing “order to the chronic chaos in which I have been living and functioning,” participated in the life of the church.

In December 1944 there was a dinner with what Thurman called an “interracial menu.” Thurman cooked 122 pieces of fried chicken—he was an excellent cook—and “a Filipino gentleman prepared the Filipino sauce in which the chicken was steeped, and Miss Ishida, our temporary secretary, prepared the rice.”

In December 1944, after the US Army announced that the official exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast would be lifted, the Gannon Committee, a California State Senate “fact-finding” committee, publicly declared that the “overwhelming opinion” of Californians was against the return of Japanese Americans, and warning of violence against resettlers.

Thurman signed a petition prepared by the Pacific Coast Committee on American Principles and Fair Play that refuted such claims and denounced the Committee for its “gospel of fear” in predicting violence.

In 1945 Thurman and Joe Grant Masaoka of the Japanese American Citizens League attended together the eleventh anniversary celebration of the Northern California Chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, and reported on the problems facing African Americans and Japanese Americans.

In December 1946, Thurman was principal speaker at the Annual Dinner of the California State Council for Civic Unity, a San Francisco-based interracial group heavily engaged in promoting Japanese American resettlement. According to the Nisei newspaper Progressive News, Thurman “stressed the importance of continuing the tremendous gains in race unity which grow directly out of wartime conditions, into all future programs of inter-race relations.” By the following year, Thurman had joined the board of the organization, renamed the California Federation for Civic Unity.

Thurman’s support was greatly appreciated by Japanese Americans. Tomi Fujino, who heard Thurman speak at a national convention of the Young Women’s Christian Association in San Francisco in March 1947, described him as “inspiring.” Japanese Canadian Norah Fujita, who was sponsored by the activist group Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy to attend an Inter-racial Workshop in Washington DC in Summer 1947, reported in The New Canadian that she was particularly inspired by hearing Thurman’s words comparing the sufferings of African Americans under Jim Crow with those of the Apostle Paul when set upon by mobs and Roman police. “And the depth of loyalty, charity, and forgiveness of the American Negro Christians is something before which we can all stand in shame.”

© 2021 Greg Robinson; Peter Eisenstadt