Professor Imayuki calmly analyzes the issues he sees and hears about in the field and has written down his own theories and mindset regarding "moving overseas," so I would like to introduce some of these to you.

- The education problem in the interior of Brazil and Paraguay is serious, with many elementary school students failing or dropping out. However, the relaxed half-day class system and the acceptance of teachers having second jobs are better than Japan's cramming classes.

- Japanese language schools in large colonies before the war maintained strict education and discipline similar to those in Japan, so students' Japanese language skills were quite high. Some graduates went on to higher education in Japan. However , the closed nature and exclusivity of these schools needs to be improved.1

- Too much emphasis on Japanese language education. Portuguese is not learned accurately, and it is mixed with Japanese accent, which is a disadvantage when it comes to going on to higher education such as university and finding a job. We recommend that children interact with Brazilians as early as possible in their childhood to learn Portuguese accurately, and that the whole family work together to help children learn Portuguese.

- Socially, second-generation Japanese Brazilians are Japanese-Brazilians, and they also have the qualities of true Brazilians. They may have been at a slight disadvantage at first, but the Japanese are hardworking, honest, sincere, brave, willing to go anywhere, and have the ability to adapt, so they are able to live healthily even in the depths of the Amazon. They are reasonably well-educated and progressive, and some have ventured into all sorts of fields and created new industries. They have achieved things that Brazilians and Europeans could not, and are truly welcome immigrants to Brazil and other countries. However, as can be seen from the immigration bill, not all Brazilian scholars and politicians are pro-Japanese, and some are ultranationalists and white supremacists. As Brazilians, second-generation Japanese should use their abilities to contribute to the development of Brazil.

- If Japanese Americans want to further improve their social status, it is important that they enter politics to strengthen their political power. It is unfortunate that many Japanese voters abstained from voting and multiple Japanese candidates are competing for votes, making their chances of winning seem remote.

- Moving to South America is a personal decision. If you are interested, you should give it a try, prepared for the tropical rains and endemic diseases. The pros of moving vary from person to person, and there are suitable and unsuitable places to move to depending on your family structure and personality, so it is difficult to say which place is best.

- Excessive subsidies and loans to migrants are not advisable. Loans have a high risk of defaulting and can weaken the resolve of migrants. There are no countries in South America where it is easy to get rich quick.

He also states the presence of Japanese people who immigrated to South America as follows:

"Over the 30-odd years from the end of the Meiji era until the outbreak of war, the Japanese government spent 30 million yen to subsidize immigrants' travels, which is equivalent to 1 billion yen in today's money. In contrast, immigrants from South America spent 1 billion yen a year in Japan, and exports to Japan totaled 3.5 billion yen. In addition, they sent considerable amounts of money back to their home countries, undoubtedly bringing great benefits to Japan."

These are the basics of social integration in a new place of residence that are still relevant today. At the time, there were much more limited options than there are now, and immigrants must have required a lot of determination and perseverance. For Imayuki Sensei, who retired and undertook this study trip at the age of 62, reuniting with his students in the new place of residence, something he found deeply moving, as can be seen in "Traveling in South America 2. "

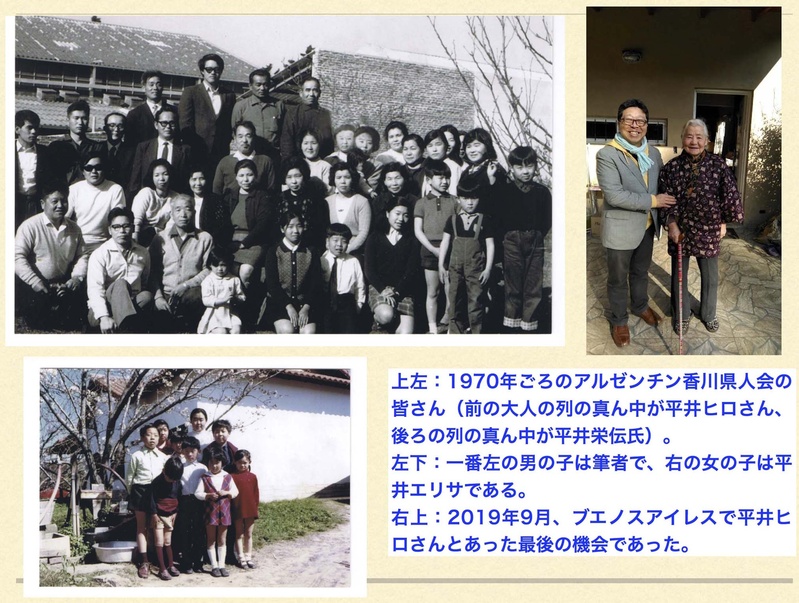

In each place, he was greeted warmly by his students, brides he cared for, senior immigrants and their descendants, and he said that partings were always very difficult. When Imayuki visited Buenos Aires, nine of his 14 students invited him to their homes one night each day and spent the night with their families. The students testified that what they learned from their teacher in Kagawa was not only useful for agriculture, but also for life planning and living.

Notes:

1. Japanese language schools in postwar Japanese settlements in Paraguay and Bolivia started out as private schools, but gradually they were organized and approved by local authorities to be incorporated into the official education system. Now they are private schools that anyone can attend, regardless of whether they are Japanese or not.

2. "Travels in South America" (published by the Kagawa Prefectural Public Relations and Documents Division, 1957) is a book that contains excerpts from the "South American Colony Inspection Record" that Imayuki recorded and co-authored with Governor Kaneko.

© 2021 Alberto Masumoto