While West Coast anti-Asian racism is well-known as a cause of the forced removal of Japanese Americans during World War II, the complex history of intergroup relations between Japanese Americans and Black Americans during and after World War II still remains rather unexplored.

In recent years, scholars and activists have begun to better understand the relationship between Japanese Americans and Black Americans. Cheryl Greenberg has studied the reporting of forced removal in the Black American press, while Greg Robinson rediscovered the important story of civil rights attorney Hugh Macbeth’s outstanding wartime efforts to defend Japanese Americans.

A series of historians, including Kariann Akemi Yokota and Scott Kurashige, have written on the evolution of Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo/Bronzeville district. One lesser-known story that furthers our understanding of this relationship is the life work of civil rights activist and academic Edmonia White Grant (later known as Edmonia Davidson). As both a scholar and activist from the Jim Crow south, Edmonia White Grant was one of few Black American women to rise to prominence and speak about the issues of race relations, and represented the ideals of the Double Victory campaign against racism abroad and at home during World War II.

Edmonia White (named for famed sculptor Edmonia Lewis) was born on July 20, 1903 in Nashville, Tennessee, to George Richardson White and Hortense Stone. Growing up in the segregated South, Edmonia White attended Nashville’s all-black Pearl High School (presently named the Martin Luther King Magnet School), where she graduated in 1916. After taking classes at Fisk University, White moved to Washington, D.C. to attend Howard University, graduating in 1924. After earning her bachelors, she returned to Nashville.

In the years that followed, Edmonia White married Francis Grant, and worked as an elementary school teacher. White was “activist minded,” in the words of historian Phillip Johnson, and in addition to her teaching, White began a lifelong mission as a black community leader during this period. She served as secretary for the Nashville chapter of the NAACP, and later as secretary for the Nashville YWCA. In the late 1930s, she joined the interracial civil rights group Southern Conference for Human Welfare, where she rose to the position of top administrator.

During these years, Edmonia White Grant enrolled at Fisk University, where she earned a master’s in education in 1933. While studying at Fisk, she began working under the famed sociologist Charles S. Johnson. After White completed her masters, Johnson hired her as a full-time research associate. In a period when the NAACP shifted its focus to the legal struggle against segregated schools, many of White’s projects with Johnson likewise focused on the importance of education.

In September 1941, Grant served as a field researcher for Johnson’s study on segregated schools in Louisiana, specifically studying the factors contributing to detrimental effects of segregation on black Americans. Grant’s assistance proved influential to Charles Johnson, and her research contributed to the publication of Johnson’s famous 1941 work Growing Up in the Black Belt and Gunnar Myrdal’s famous 1944 study An American Dilemma. Johnson’s project also foreshadowed Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s celebrated “doll” studies on the psychological impact of segregated schools on black children.

In 1941, Edmonia Grant became the college field representative for the national Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in New York City. During this time, in the wake of Executive Order 9066, Grant began studying the plight of Japanese Americans. In December 1942, with sponsorship from the National Intercollegiate Christian Council, she published a pamphlet titled “Fair Play for American Fellow Students of Japanese Descent”. In addition to citing the dangers of forced removal to American civil liberties and deploring the financial toll of the incarceration on its victims, Grant underlined the Christian duty of Americans “to help these students attend colleges and to help re-establish them in a normal student life.” The pamphlet was later cited by multiple Christian groups and academics as a significant publication advocating Christian support for Japanese Americans, including sociologist Joseph Roucek in The Journal of Negro Education. The pamphlet was featured in the December 24, 1942 issue of the Rohwer Concentration Camp’s newspaper The Rohwer Outpost.

In late 1943, Grant undertook a nationwide speaking tour, during which she visited multiple camps. In early December 1943, Grant and Marian Brown Reith of the West Coast YWCA visited Gila River to meet with Nisei students hoping to study at outside universities (ironically, Fisk University, like other HBCUs, was excluded from the NJASRC list of acceptable institutions, though it did have on its faculty the Japanese American sociologist Jitsuichi Masuoka). Grant continued to send pamphlets related to her work to the Gila River students, and was later acknowledged in the March 1944 issue of the Gila River student newspaper The Phalanx Fraternity Tribune.

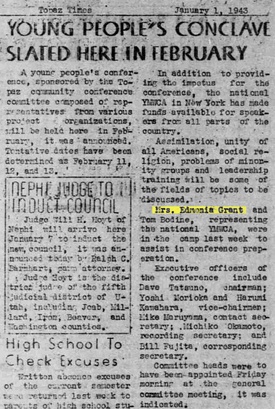

Grant’s tour continued with a visit to Topaz. On December 24, 1943, Grant accompanied Tom Bodine, the field director of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, on a weeklong Christmas visit to Topaz. On New Year’s Day 1944, the Topaz Times reported on Grant and Bodine’s collaboration with JACL leaders like Dave Tatsuno in organizing a “young people’s conference” in February 1944. The conference, funded by the National YWCA, presented discussions over questions of resettlement and assimilation, as well as larger issues facing minority groups.

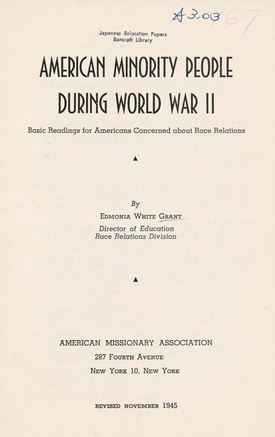

Following her return to the East Coast, Grant was hired by the race relations division of the American Missionary Association (AMA), the sponsoring organization of Fisk University. While at the AMA Grant authored a second pamphlet on Japanese Americans, which also formed part of a reader on American race relations during World War II. Titled “American Minority People During World War II,” the pamphlet listed major works written on Japanese Americans during the war by writers such as Carey McWilliams, along with the JACL newspaper Pacific Citizen.

Grant’s support of Japanese Americans coincided with her own ongoing work to combat racial discrimination. In April 1943, Grant spoke before a rally of the Communist-allied group National Negro Congress at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York City, on the realizing of “full economic and civil rights” for African Americans. Speakers also included New York councilman and future U.S. representative Adam Clayton Powell, Jr, National Negro Congress president Max Yergan, and New York Congressman Vito Marcantonio.

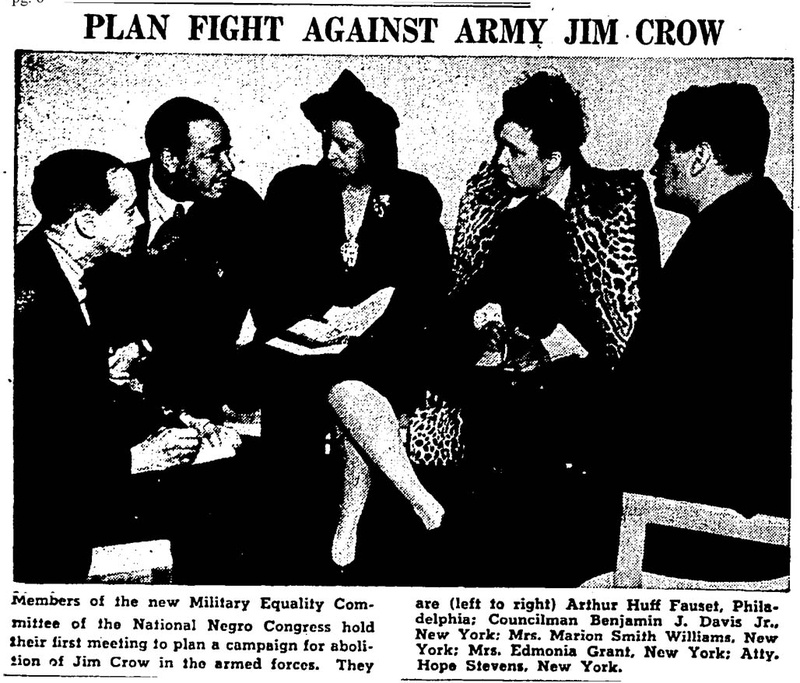

In 1944, Grant then joined the National Negro Congress’s Military Equality Committee, as part of lobbying efforts to desegregate the U.S. Army.

Following the end of World War II, Grant continued her race relations activism. In 1947, along with W.E.B. DuBois and other Black American leaders, Grant signed a petition in support of Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party presidential candidacy, citing Wallace’s promises to reinforce anti-lynching laws and end poll taxes in the South.

In July 1947, Grant went to Atlanta, Georgia and spoke before a convention of Black American nurses, declaring that Americans “must abandon competition between racial and national its groups and secure their cooperation.”

In 1948, Grant began work on the Freedom Train, an early Civil Rights initiative to challenge segregation in the Deep South, as part of her work with the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (SCHW). Grant extolled in a January 1948 article for the Philadelphia Tribune that the Freedom Train project needed to be managed by an integrated planning committee, a criticism of the early initiatives which only included white planners. While the Freedom Train was successful in garnering attention to segregation as a problem in the American South, it failed to address the concerns vocalized by Grant, as train cars remained mostly segregated despite occasional appearances of integration.

At the same time, Edmonia Grant and members of the SCHW were mentioned by name in an attack on the organization by Congressman John Rankin. A white supremacist known for his attacks on Black Americans and one of the first elected officials to call for mass incarceration of Japanese Americans in 1941, Rankin attacked the SCHW as a Communist front that promoted un-American principles. The criticism helped usher in the end of the SCHW. Shortly after the dissolution of the SCHW, Grant joined the National Council of Negro Women.

In 1948, Edmonia White Grant divorced her husband Francis Grant. Two years later, Edmonia White remarried Eugene Davidson, a Washington, D.C. lawyer and civil rights activist who testified before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 1939. Eugene Davidson was likewise a longtime friend of scholar/activist W.E.B. DuBois, and DuBois congratulated the newlywed couple on their wedding.

Along with her ongoing mission to tackle racism against Black Americans, Edmonia Davidson continued to speak out for Japanese Americans. Davidson voiced her support for the acceptance of Japanese war brides arriving to the United States in a November 1950 article for the Pittsburgh Courier, noting the racist intentions of the marriage ban and the double standards of the ban on Japanese, as compared to the welcome offered European war brides.

In 1948, Davidson was hired by the education department at Howard University. After receiving her PhD from Columbia University in 1958, she became a full professor at Howard. During her time at Howard, she authored two books on adult education, and also penned numerous articles for The Journal of Negro Education. After the dissolution of the SCHW, Grant joined the National Council of Negro Women to continue her activism. In the period following her retirement in 1974, Edmonia Davidson moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She died there on August 27, 1992 at the age of 89.

The life story of Edmonia White Grant is important not only for her work as a civil rights activist during some of the crucial moments of the civil rights movement, but also her universal approach to race relations. Likewise, Grant was also one of the few Black American women, along with Erna P. Harris and Pauli Murray, to speak against the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war years. Her ongoing activism for Japanese Americans and visits to the camps is additionally telling of the combined mission of Black American activists to challenge the various forms of white supremacy beyond the Deep South.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen