John Mitani spent his entire faculty career at University of Michigan (U-M), a career that was not available to either of his parents. Now the first-generation student scholarship he established in their name will help other students spark the passion that leads to their degree.

* * * * *

In the summer of 2019, at the Pioneers in Primatology symposium at the annual meeting of the American Society of Primatologists, John Mitani, emeritus professor of anthropology, was asked to give a talk about his career. He had completed teaching his final semester at U-M, where he’d spent his entire career. He had a lot of material from which to draw.

In his 41 years of fieldwork as a primate behavioral ecologist, Mitani has studied the social behavior and communication of all five of the non-human apes: the gibbons and orangutans of Indonesia, gorillas in Rwanda, bonobos from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the chimpanzees of Uganda and Tanzania. “I could claim that my entire career was planned,” Mitani said to his audience that day, ”but that would not be true. As scientists, we are trained to design and execute carefully controlled studies, but more often than not things do not work out as planned. If there is any coherence to my research, it is accidental. My story emphasizes the role that serendipity plays in science.”

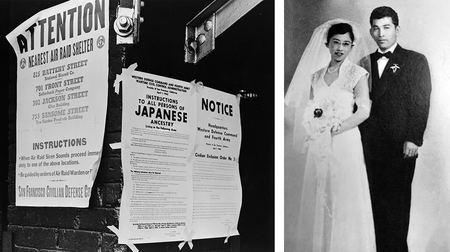

Serendipity had recently been making appearances in other parts of Mitani’s life too. The Leakey Foundation, which had funded some of his research, is headquartered in the Presidio of San Francisco. It had been a military post since the eighteenth century, when the Spanish colonialists first erected el presidio, until it became a national park in 1994. Visiting the foundation in 2019, Mitani came across an exhibit about the Presidio’s role in forcibly removing and incarcerating 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. The exhibit marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Civilian Exclusion Order, which had come from a Presidio corner office.

In the exhibit, the names of all of the 120,000 people who’d been interned were stenciled onto glass, and Mitani’s parents — Sally Sadako Oshita and Don Kiyoshi Mitani — were among them.

Chance crossed Mitani’s family history with his research again later. The Leakey Foundation was organizing a meeting in Wyoming, and a trustee who lived there was telling Mitani about an interpretive center at Heart Mountain, near Cody. “And I realized,” Mitani recalled, “my father had been interned there.”

After four decades of field research, Mitani knows how to distinguish significant moments from thousands of hours of observation. Many of these moments have been captured in Rise of the Warrior Apes, an award-winning documentary on his research, and in Chimpanzee, a Disneynature film.

Other significant moments have mostly been private. Mitani knew members of his family had been interned, but, like many members of their generation, his parents didn’t talk about it. Mitani’s father, who’d been raised in Hiroshima’s mild climate, would occasionally tell his sons about Heart Mountain’s fierce winters. Mitani’s mother, who had been interned in Poston, Arizona, recalled the tar paper shacks she and others lived in and how little privacy they offered. Both of his parents noted the camps were located in desolate regions in the country’s interior. There was an obvious reason for this, Mitani says. “The U.S. government wasn’t keen to advertise what it was doing to some of its citizens.”

No-no Boy

At family reunions, Mitani says, all the cousins get together. “Some of us are too young, but others had been born or had partly grown up in camp,” he says. “But all agree that our parents never willingly talked about it.”

But Mitani’s father did talk about one thing: being a “no-no boy.”

At Heart Mountain, the United States government asked men to answer 28 questions to determine if their loyalty was with the United States or Japan. Many questions asked ordinary things — names of family members, education levels, language skills — but the last two questions went directly to the heart of the matter: Would the men willingly serve in the armed forces? Would they swear an unqualified allegiance to America? Mitani’s father answered no and no, which made him an infamous no-no boy.

Most no-no boys were interned at Tule Lake, California; Mitani’s father had been there, but he was transferred to Heart Mountain. “Why he was able to remain at Heart Mountain is a mystery to me,” Mitani says. When there was seasonal work outside, Mitani’s father would change his answers to yes, yes. “But as soon as he got back to camp he would go back to no, no. Perhaps this was why he wasn’t moved back to Tule Lake or incarcerated.”

Other parts of his parents’ lives also remained a mystery, including the Japanese language, which is one of Mitani’s greatest regrets. He was never able to speak Japanese with a Japanese colleague who became a very close friend. Even visiting Japan could be painful. “They look at me and they think something’s off,” he says. “Now my wife, who is not Japanese, protects me. They see her, they see me, and they can figure things out.”

The sense of isolation was painful, but it offered Mitani access and empathy to others’ struggles to navigate their own alien and intermediate spaces. In 2017, when U-M students launched the Being Not-Rich at U-M website for fellow students also making their way through U-M without enough resources, it struck a chord in Mitani that kept resonating. At the same time, as Mitani unexpectedly encountered his parents’ history in his professional life, it felt less like worlds colliding than marveling at the turns of fortune that had brought him to where he was. Because his parents had been interned, they had been denied the chance to go to college. He decided to create the Don Kiyoshi & Sally Sadako Mitani Endowment fund for first-generation students pursuing a degree in anthropology at LSA (College of Literature, Science, and the Arts).

“I’d been thinking about my parents and about the Being Not-Rich at U-M website. I’ve been a faculty member here my entire career, and I’ve always been tremendously grateful for how supportive this place has been — not only my department, but the college and the entire university. I think it was the confluence of all these events that made me decide to do this. I’ve had a long, happy, and fulfilling life here.

“Given their upbringing and background, I’m not sure my parents really understood what I did, but they were always tremendously supportive of everything I did,” he says. “This is just a small way to pay it back.”

*This is an article from the spring 2020 issue of LSA Magazine.

© 2020 Susan Hutton / LSA Magazine