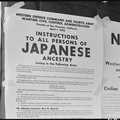

Moldering away in the concentration camps during WWII as a kid was bad enough, but repatriating to Japan right afterwards was something else again. My father, mother, and I got on the round-bottomed troop transport at San Pedro, California in February 1946 and began the 10-day journey across the Pacific. We landed at Uraga and were handed over to the Japanese authorities and lived in the barracks of the former Japanese naval base. The transfer was immediately noteworthy: from dining on swiss steak, mashed potatoes, carrots, bread, and ice cream aboard the U.S. vessel to a thin gruel with two grains of barley and two inedible surplus hardtack. We spent two weeks in the barracks while our papers were being processed.

I didn’t want to go to Japan. Neither did my mother, a Nisei. My father, an Issei, opted to return, saying he doubted Japan had lost the war and could not accept the fact that she had surrendered unconditionally. Propaganda, he declared as he spread his pro-Japanese rhetoric among the inmates of the Crystal City camp, much to the chagrin of the Nisei in camp.

I didn’t want to go because I was a Sansei kid who didn’t know a lick of Japanese or Japanese culture. I would miss my comic books, the radio programs (Fred Allen, Red Skelton, Our Miss Brooks), my favorite foods (the ubiquitous hot dogs). My father, aloof in his private Japanese domain, didn’t teach me anything, nothing about Japan, the Japanese or her culture. Nothing. I was left to fend for myself.

When I learned that he had made up his mind to return to Japan, I pulled out of the sixth grade American school to go to the Japanese school to learn some of the language in preparation. After a year, I learned next to nothing—except I was good at handicrafts.

It didn’t serve me in good stead in Japan. All it did was to attract a bunch of curious teenagers who marveled at my adeptness at making a basketball game, a pinball machine and a model airplane. They did not befriend me. After all, I was that lookalike American kid who had stupidly come to a prostrated country defeated in no uncertain terms by the land of his birth. I was fair game and could not, try as I might, get in with my teenage peers. I got in only so far as to be tolerated. Otherwise, I was ignored and not included, even in their conversations. And so my 13-year isolated exile began…17 years, including the four years out of mainstream American society due to the mass evacuation.

I was cast on my own resources. But my understanding of anything was limited. I knew next to nothing about life, people, society, customs, conventions—or anything. The confusion and culture shock hit me like a massive hemorrhage. I had no point of reference, neither knowledge nor experience. I was a walking target—with a bullseye on my back—for the opportunists, even from the way I walked. They would point to me and holler: “Kompas’ ga nagai!” His stride is so long. I thought I would be accepted if I adjusted it. I did. I tried walking like a Japanese…short steps. To no avail. At 13 the die had already been cast. I was already American. Too far gone. That, combined with my tainted accent branded me an outsider American, a gaijin lookalike.

Being an American was an identity that I struggled to preserve throughout my questioned sojourn in Japan. The double masks were forever turning East—and West. While trying to assimilate, I was the diehard American who sang all the American songs he could remember, including, of course, the national anthem and “God Bless America”. Unsure of my memory, I substituted the line “God shed his grace on thee” with “God bless thy very name”, so homesick was I for the land of my birth and to hear English spoken. I had only my mother to talk to—which was infrequent. She had problems. My father did speak English but only a personal, broken variety. So he was no help.

But I toughed it out. I had no choice; I was cast on my own meager resources. Once I contracted TB and experienced night sweats and coughing. The doctor had no medicine to give me in those years right after the war. He said to shred persimmon leaves and make a tea out of it and drink it. I did. But it was too bitter and worked too slowly, though it was supposed to supply me with extra vitamins. So in disgust, I took to running up the steep path of the mountain behind our abode, working up a sweat to exhaustion. After about a month of the regimen, the night sweats and coughing stopped, and the doctor declared me cured after the X-rays showed nothing.

The sanitary conditions were primitive. The toilet was a hole in the floor, and we shat into a pit which was periodically emptied by the farmers who then spread the excrement on the vegetables: nappa, sweet potatoes, pumpkin, daikon…everyday veggies that kept us alive. But they produced belly worms that I had to get rid of with a heavy dose of santonin after experiencing the characteristic anal itch. I was lucky. The worms could have laid their eggs in the brain and nest there, but I was the average host, and they migrated to their standard nesting grounds in the intestines.

There were all kinds of epidemics that swept the land. The most dreaded were cholera and sleeping sickness. We had to boil the water even though it came from a deep well. And I was always on the look out for the carrier of sleeping sickness, a red-banded mosquito that stuck its sucking tube at right angles. I was constantly swatting mosquitoes off me, both regular and the red-banded ones. And mosquitoes were everywhere. We had to sleep with mosquito netting and repellant burning by our heads. Typhoid and typhus were also rampant. Due to the lack of sanitation, infections were rife. A small cut could fester and cause serious damage. A small wound on my foot and a pimple on my chin turned into an aodaisho, a gangrenous carbuncle with a green plug. I still have the scars today.

So many things happened so fast in war-torn, postwar Japan that I began to look at things in the manner of anticipating adventures. Coming to Japan was an adventure. What next? It seemed to my young mind that life was always a life or death struggle. Life was a fight. Was I equal to it—or not? Well, after eighty-eight years, I have to claim I am. And I claim bragging rights.

The town of Unomachi, nestled among the picturesque mountains of Higashi Uwa County, is situated south of Matsuyama, the largest city and capital of Ehime Prefecture. To its south lies Uwajima, a port city on the southern-most tip of Shikoku Island. Unomachi was where I stayed from 1946 to 1950, and I fell in love with the region. Its Meiji Era lifestyle and pace were something that drew one into the very essence of the Japanese character—for good or ill. The town represented a microcosm of Japanese society. It had a large elementary school, a middle school and two high schools, one specializing in agriculture. And baseball was very popular. I had brought along my Rawlings fielder’s glove, so owning a piece of baseball history automatically placed me on the local middle school team. I was made the pitcher.

The valley in which the town was located was landlocked and connected to the outside world through two tunnels, north and south. To the east over the mountains lay Kochi Prefecture and to the west, Hokezu Toge Pass which descended down to the Uwa Sea, part of the Inland Sea. It was here that I was awakened to nature. The descent down to the seashore where a small fishing village stood was lined by groves of Iyo-kan tangerines and grape fruit. Uwa Sea was a miniature garden dotted with emerald islets here and there, shrouded in a mist, lying in a slate-blue sea marked by the tailing white wash of fishing boats. In summer when the groves groaned heavily of fruit, one could see to the south the islands off Uwajima. It was but an hour’s train ride away.

The valley was like a garden also. I would climb up the mountain by our house with my watercolors and paint the panoramic scene of the valley below. The Uwa River ran sinuously the length of the valley, covered with stretches of sasayabu, bamboo brush. From the vantage point on the side of the mountain, I painted the tiny box-like houses, all with uniform gray slate roofs; the ribbon of dirt roads where three-wheelers kicked up dust; the quilt-work patches where the farmers methodically swung their grub hoes; the baseball field belonging to the agricultural high school. Sometimes a song would come wafting up to me. Someone would be singing the popular song, “Akai ringo ni kuchibiru tsukete…” I hummed the catchy tune as I painted.

To eke out the calories of our meager diet of sweet potatoes, dried fish, and barley rice (sometimes), I used to shoot sparrows with my air rifle that I purchased second-hand. It took quite a few sparrows to make a meal. But during the winter months particularly, they would be plentiful and perched on the overhanging wires and branches. I would step through the snow in my sashi-geta, my feet clad partially in a thin, undersized tabi, and braving the cold would try to remain as inconspicuous as I could, concealing the rifle by my leg, and at the last moment whip it into action to down a sparrow. They were alert to anything resembling a rifle—a broom stick, for example—and flee at the sight of it. So shooting sparrows was always a hit or miss proposition.

At other times, I tried my hand at trapping eels in the Uwa River. I would get up early in the mornings and hike down to the river in the dark so as to avoid prying eyes and anchor the traps baited with worms on the bottom. Then later that day I would retrieve the traps which usually held an eel or two—they were plentiful in those days—and bring them back home to prepare. They were delicious and added much to our diet.

My education in postwar Japan suffered. I got good enough grades at the Japanese schools, but my English was in disrepair. I was in danger of losing it and read aloud an old copy of Reader’s Digest to keep my tongue limber and my ear attuned to the language. But, lo and behold, the small local library got a shipment of books in English, and I spent an entire summer vacation devouring its contents, reading twenty hours a day, just absorbing the written English word covering literature and history. It was my early self-guided education. Although I didn’t understand many of the words (I didn’t have a dictionary), I plowed through the works and through osmosis absorbed—sucked up—the contents as though I was dredging. I think the experience helped me succeed in my studies later at St. Joseph International School (then known as St. Joseph College), a high school taught by the Marianist brothers.

All in all, my sojourn in postwar Japan taught me a great number of things about life. It was the matrix of my development as a person. I tried to get in with the people, but I was forever the outsider and I compensated for my lack of human engagement by loving the garden-like picturesque scenery, the culture and the food of Japan. I believe I single-handedly propagated sushi to the outside world.

© 2021 Roberto Kono