In Eagles of Heart Mountain, football is all but pretext. The book, journalist Bradford Pearson’s debut, follows the high-school football team that formed at the Heart Mountain concentration camp during World War II. Despite being made up mostly of boys who had never played football before their arrival at Heart Mountain, the Eagles competed against local high school teams and finished their first season undefeated. After two chapters closely following the team’s main players and their families, though, the book opens outward, becoming a broader story about the racist and economic motivations that led to the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

“I sort of went through this process thinking about the book as this Trojan horse,” Pearson said in a video interview, “especially with the cover and the title. Because I was like, if I can convince white baby boomer dads to pick up a book about football and war, I can actually teach them about all these other things.”

Pearson first learned about the Heart Mountain Eagles on a 2014 visit to the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center while he was in Wyoming doing reporting for a different project. “The moment that I came out of that museum at Heart Mountain, I still remember how embarrassed I was by how little I knew about the history of Japanese American incarceration,” he said. “I guess at that point I would have called it ‘Japanese internment’; that's how little I understood that world.”

The Eagles had only a small note in the larger exhibit, but as a former high school and college rower, Pearson was drawn to the story of these teenage athletes, who were forced to leave their homes and their school teams for a concentration camp in remote Wyoming, their aspirations for the future postponed or derailed altogether.

After returning home, Pearson kept thinking about the Eagles, and how they might provide an entry point into a story about racism in the United States. Not sure whether this developing idea would turn into a magazine article or a book, he reached out to Heart Mountain Interpretive Center to begin his research, and the center connected him with Bacon Sakatani, known as “Mr. Heart Mountain,” who gave him a CD containing the archives of the Heart Mountain Sentinel and Echoes, the camp newspaper and its high school counterpart.

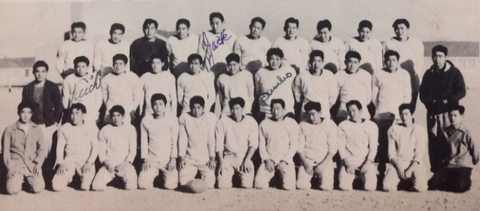

In the evenings after his day job as the features editor at Southwest’s in-flight magazine, Pearson would read through the newspapers, and from them, the main characters began to emerge: Tamotsu “Babe” Nomura, rising football star at Hollywood High School; Keiichi Ikeda, who made his high school baseball team but was sent to camp before he could play a single game; George “Horse” Yoshinaga, who began his writing career at Heart Mountain and went on to become one of the best-known Nisei columnists in America.

When Donald Trump was inaugurated in 2017, Pearson had a reckoning, asking himself what he could do with his skill set to push back against the tide of bigotry and disinformation. At the magazine, he had limited ability to tell stories with a political agenda, so he began working on the Eagles story in earnest. He remembered the embarrassment he felt walking out of the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. “I thought, okay, if I know very little about Japanese American incarceration as someone who has studied history and is a journalist and grew up in Franklin Roosevelt's hometown, then 99% of Americans know less about it than I do, probably,” he said. Maybe through football, and the universal experience of being a teenager, he could bring the story to a wider audience.

Pearson began reaching out to the players’ families, and the first to respond was Jan Morey, Babe Nomura’s daughter. “Little did I know, but before she emailed me back, she had done her research on me to make sure that I was legit,” he said, “going so far as to call Southwest Airlines to make sure that I was who I said I was. Which is something that she didn't tell me until after the book came out.”

After their first phone conversation, she became his gateway to the rest of the Eagles, encouraging Yoshinaga’s family and Ikeda to talk with him. Eventually she even invited him to stay at her house on his reporting trips to Los Angeles, feeding him breakfast and sending him off into the field with snacks.

As a white journalist coming into the Japanese American community from the outside, he didn’t want to write a book without the families’ sign-off. He knew that he was in a privileged position, with a book deal that paid enough to allow him to treat the book as a full-time job for two years. “If I failed at that, I would view it as a personal failure,” he said, “but then also on a much broader scale, it would be a failure from a publishing standpoint, from a political standpoint, from a historical standpoint. I knew that I needed to work really hard at this.”

That pressure was also not unique to white journalists, he learned, while doing a panel event with Shirley Ann Higuchi, author of Setsuko’s Secret. “I thought that there was pressure on me because I was a white journalist writing about this community. And she said, well, there's a completely different pressure on me as a member of the Japanese American community writing this story,” he said. “And that was, sort of embarrassingly, the first time I had thought about how heavy that burden must be for Japanese American writers who are trying to tell this story as well.”

Pearson immersed himself in books and oral histories, steeping in information so that he would be able to craft a narrative from deep understanding, rather than relaying one fact at a time. He began going on the annual pilgrimage to Heart Mountain, where he stuck out as one of few white people and tried not only to gather information but also to show that he hoped to become a real, lasting part of the community.

On his trips to Los Angeles, where he stayed with Jan Morey, he spent time researching at the Japanese American National Museum, where he also interviewed Keiichi Ikeda, one of the last surviving Eagles and the only one he was able to interview for the book. He visited the Santa Anita Racetrack and snuck into the stables to see what it may have been like for the Eagles who were forced to live there. He drove to the Nomura family’s old boarding house in Hollywood and snuck in there too.

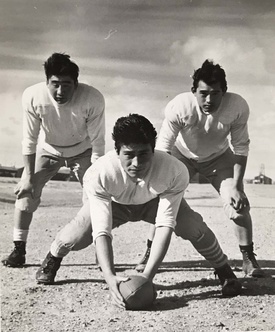

In addition to this in-person research, he also relied on photographs and newspapers, especially the Sentinel and Echoes. He read through every issue, not just for the sports stories or major news but for small details, like one brief mention in the Sentinel about women picking wild greens and pickling them into tsukemono. The photographs also helped him build the book’s scenes, providing information like what the football field was like, how many people deep the crowd gathered at games, and how the characters looked at different points over the years (like George Yoshinaga’s father, Usaburo, with “an anvil of a haircut” and “a permanent glower”; or Babe Nomura, the too-long sleeves of his jersey “scrunched over his elbows.”)

Managing the research for a 306-page first book, Pearson said, was an organizational nightmare. From the camp newspapers, he transcribed all the stories he thought he might need, in order to create a searchable database. The book’s mostly chronological structure revealed itself to him only after he made a huge timeline, covering everything from the Eagles’ games and the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee’s actions to the landslide that formed Heart Mountain’s namesake 50 million years ago, as well as tangential ephemera that ground the book in the larger surrounding world, including a jail break at Alcatraz and Buffalo Bill’s part in developing the town of Cody, Wyoming.

The book’s strength lies in its specificity and its expansiveness; it zooms both far out in time and scope and close up to individuals and small moments of their lives. Without mentioning the present, it still draws a clear parallel, especially through direct quotes that show that even in the 1940s, incarceration was debated, not a foregone conclusion. The back-and-forth of racist rhetoric and calls for recognition of shared humanity mirror the discourse of modern politics, making the history feel uncomfortably close. While working on the book, Pearson noted one parallel after another—the Muslim Ban, separation of families at the border, disinformation that stoked racist resentment—culminating in the insurrection on the Capitol the day after his book came out.

Meanwhile, all this history is personalized through sensitive close characterizations made possible by deep research. We learn that when they filled out the infamous loyalty questionnaire, “Babe filled out the form in pencil, in a quiet, stylish cursive that would bring him pride for the rest of his life… Horse filled out his form entirely in capital letters, save for his i’s.” Even those people who only appear in the book for a couple of pages or paragraphs are described with care, like Mas Ogimachi, an Eagle who dreamed of becoming a certified public accountant, but because of the timing of the incarceration and the draft, never did. Still, “every year until his death in 2017, Mas would do his taxes by hand, without a calculator.”

“I really wanted to try to find as many of those details as I could to paint everyone as the whole people that they were,” Pearson said. “For me it was especially important to do that because the people in this book had, in a lot of ways, their personalities and humanities taken away from them when they got sent to camp. They were imprisoned because they were viewed as this monolithic quote ‘enemy,’ so what I wanted to do was show them as individuals, to try to show the reader that, even though I expressly say there was no reason for these camps, to show on a person-to-person level, on a human level that each of these people were so different.”

* * * * *

Author Discussion—Eagles of Heart Mountain with Bradford Pearson

Saturday, November 20, 2021

Bradford Pearson will be at the Japanese American National Museum to discuss Eagles of Heart Mountain, in conversation with curatorial assistant Erin Aoyama to discuss his new book that explores the complicated connections between football, hope, and resilience in this virtual program. Click here for more information >>

Eagles of Heart Mountain is available now in the JANM Store.

© 2021 Mia Nakaji Monnier