Star Nursery Losses During and After Camp

When the Uyematsus left for Manzanar, F.M. Uyematsu planned to continue his lucrative Star Nursery business. However, F.M. faced unimaginable difficulties trying to oversee Star Nursery from behind barbed wire. He was limited to correspondence, which his daughter Alice translated, and at least two in-person visits by permission of camp authorities.

He left the business with an acting general manager named H.A. Robinson, who after just over a year wanted to declare Star Nursery bankrupt. With the help of attorney J. Marion Wright, R.W. Augspurger took over management to keep the nursery functioning. Augspurger made several trips to Manzanar to meet with F.M. under supervision of camp authorities.

This information was generously provided by Professor Wendy Cheng, who gleaned close to 500 pages of the Uyematsu family WRA case files. She provided me with copies of pertinent letters that are quoted from herein.

In a letter dated April 22, 1944, Augspurger wrote to F.M.: “… we have been subject to foreclosure on the Manhattan Beach property ever since I took over the management because of … delinquent taxes.” This is when 80 acres of the Manhattan Beach estate was sold to offset debts that had accrued.

In the same nine-page, single-spaced letter, Augspurger details how E. Manchester Boddy, owner of the Rancho del Descanso, was trying to run Star Nursery out of business:

“Mr. Boddy has been underselling us at the [flower] market and to the dealers for the past several months. While we were selling camellias at three dollars a dozen, he was selling them at 7 cents a piece. You can see that this is one-third of our selling price. Our customers continue to buy from us even in the face of these ridiculously low prices.”

Most of these accounts were national chains — Sears Roebuck, Kress & Company, J.J. Newberry, and Woolworths. He goes on to describe how upset Boddy was that he did not receive F.M.’s entire camellia stock: “I am sure that you can readily appreciate that with his supply of camellias, gardenias and azaleas and his attitude toward you and the Star Nursery that the outlook for this nursery is not a favorable one.”

When the Uyematsu family returned from Manzanar in 1945, they still had ownership of Montebello, Sierra Madre, and a reduced Manhattan Beach. This is still astounding to me, given the majority of Japanese were starting all over with nothing but the $25 they were given when they left camp.

The looting created by EO 9066 did not stop with the closing of the camps. The last parcel of 40 acres at Manhattan Beach was sold in 1947 to the Redondo Beach Unified School District for $60,000 (the district had budgeted $100,000 for the purchase). Mira Costa High School was built on this last parcel.

“Threats” of eminent domain were part of the story, for there are two high schools that now sit on formerly Uyematsu-owned property: Mira Costa and Montebello. My father, F.G. Uyematsu, told Naomi Hirahara (“Scent of Flowers”): “[The city] threatened eminent domain and said that it would go to a public court in which the jury would be white, and the city would win,” referring to the sale to Montebello Unified School District.

As Cheng summarized:

“In 1942, the Uyematsu family owned approximately 132 acres of land in three locations across Los Angeles County, and their business was thriving. Within just over a decade, all but the 7 acres in Sierra Madre was gone.” So while about 80 acres of Manhattan Beach were sold off during camp, another 45 acres were sold in the next 8 years after camp.”

Spreading Love for Flowers Through Good Will Projects

F.M. retired from Star Nursery in 1951, when he handed the reins to my father, his first son, Francis Genichiro. In several of his essays, F.M. quotes an American horticulture professor: “Those who love plants cannot be nurserymen.” Even though as a lover of plants, he emerged as a millionaire during the Depression, this philosophy guided him in his remaining years. He utilized his stature as a respected authority on horticulture to develop community/friendship projects between the American and Japanese people.

F.M.’s first kind-hearted community project took place during his early days at Manzanar, prompted by the dismal camp scene. From his biography: “In ten months, Uyematsu had his company send 400 cherry trees, 80 wisteria, and other garden trees and iron pipes for irrigation to Manzanar by two large-sized Army trucks. When he completed the park with a Japanese garden, he received tremendous appreciation from the camp dwellers.” Manzanar Cherry Park was born.

In a letter dated 1/18/68, signed by City of Los Angeles’ John H. Ward, superintendent of parks, and Richard E. Bullard, supervisor of horticulture, F.M.’s good will projects are documented:

- 1953 and 1956, “18 different varieties of well established Japanese cherry trees were planted at Bronson Canyon of Griffith Park”

- 1957, “Mr. and Mrs. Uyematsu took a gift of California wildflower seed from Mayor Poulson to Tokyo, and they were presented to Mr. Sinjiko, supervisor of the Imperial Gardens, as a gift from the people of Los Angeles”;

- 1957-58, 80 varieties “of our best roses” to Jindai Botanical Garden in Tokyo;

- 1958, “17 Mt. Fuji cherry trees grafted on American root stock were planted in the Exposition Park Rose Garden.”

F.M. wrote “The Cherry Blossom and How to Appreciate It” when he was donating 60 cherry trees over 20 years old to the City of Los Angeles at Bronson Canyon of Griffith Park. He describes his relationship to the plants he loves:

“The cherry tree holds first place among plants that I love. To it I have devoted the most time and for it I have spared no expense. … I finally realized in recent years that it is not good to keep my beloved cherry tree ‘daughters,’ who have a long future before them, near at hand to a parent who has only a few years left himself. … It was like the happy father of the bride that I donated and transplanted my cherry trees to Los Angeles.

“Among the trees I gave were ones I had prized highly through the years — ones that caused my wife to come running out of the house when she saw me digging them up and asking me in astonishment, ‘Oh, are you giving up that tree, too?’

“With a prayer that the cherry trees I donated will grow ever luxuriantly through the years to come … displaying the beauty which makes their blossoms queen of flowers in Japan, standing as a memorial to the Issei long after they are gone from this world and fulfilling their responsibility of beautifying this city, I lay down my pen.”

Sadly, L.A. City Parks did not have the expertise to keep these trees alive. After a few bountiful years, they shriveled up and died.

From his frequent visits to Japan, F.M. noticed the inferior quality of roses in Japan compared to those at Exposition Park’s Rose Garden. Through F.M.’s brokering, roses proctored from Exposition Park were gifted to Tokyo from the City of Los Angeles in 1953. The 30th-anniversary Bulletin of the North American Branch of the Agricultural Society of Japan details this good will effort:

“. . . [B]ased on Uyematsu’s project plan, the Japan-U.S. Goodwill Rose Garden donated by the City of Los Angeles was started to be built on about 6,600 square meters of the land in the Shindai Botanical Garden in Tokyo. By the time of the Tokyo Olympic Games in 1964, the splendid American roses were ready to bloom to entertain many guests. Today, propagated by the grafts of the roses originally planted in this goodwill garden, excellent American roses can be seen in almost all the public rose gardens in Japan.”

In 1957, the 18th Nisei Week Festival commended F.M. as a pioneer of merit for his distinguished services in the community. Around 1968, F.M. received the Sixth Order of the Sacred Treasure (Kun Rokuto Zuihosho) from the Emperor of Japan; the Green and White Medal for Merit (Ryokuhakuju Yukousho), and the Red and White Medal for Merit (Kouhakuju Yukousho) from the All Japan Agricultural Society.

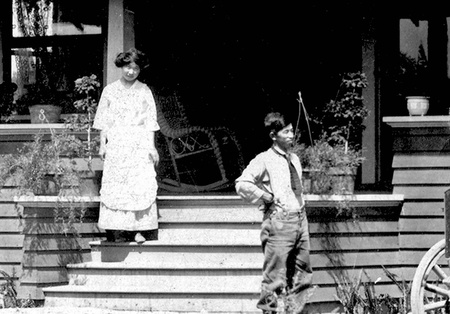

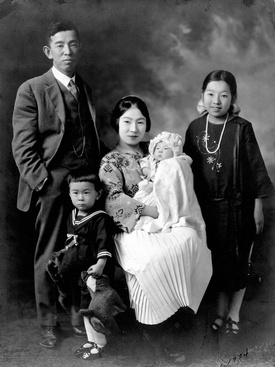

The Family Life of Grandpa Cherry Blossom

F.M. had two marriages. The first was arranged by his parents in Japan, while he was busy with the start of Star Nursery. He wasn’t planning on getting married at the time, but went along with his parents’ marriage arrangements. He sent for his new bride, and they had a daughter, Sonoko. He soon realized the marriage “did not feel right.” After consultation with his wife, Miyoko, it was decided she would return to her parents in Japan. With the wife’s consent, Sonoko would be raised by F.M. in America. She was three years old when they divorced.

Enjoying financial success on becoming Camellia King, F.M. embarked on another trip to Japan, combining business with finding a new wife. In his words: “The marriage this time was in principle based on the mutual understanding of the persons concerned.”

Not pre-arranged by the families involved, F.M. married Kuniko Watanabe in 1918. This union produced five children from 1921 to 1933 — Francis, Alice, Starr, Marian, and Sam.

Each child was taken to Japan to meet their grandparents. Francis and Alice were raised by relatives in Japan until it was time for them to enter kindergarten back in the U.S. Neither could speak any English on their first day of school. All of the Uyematsu children went to Washington Elementary School in Montebello, where my sister and I also attended in the 1950s before the family moved to Sierra Madre.

The family met tragedy before the attack on Pearl Harbor, when Starr died at 16 years of age. Tragedy struck again after the Uyematsus returned from Manzanar — Alice had contracted tuberculosis in camp. She left Manzanar in an ambulance and passed away not long after, at 22 years of age.

Sonoko married Shigezo Iwata in 1937. Even though it was arranged by a family friend/matchmaker, when rumors surfaced about Shig’s lifestyle, F.M. no longer approved of the marriage. But Sonoko and Shig continued to meet and got married despite F.M.’s disapproval. A rupture in Sonoko’s relationship with F.M. resulted and was only partially reconciled in 1962.

The Iwatas were living in Thermal with their three children when the U.S. entered World War II. Shig was quickly taken to Lordsburg, New Mexico, a high-security Department of Justice concentration camp. As a martial arts expert, and the head of Thermal’s farm association, he was considered a high threat. Sonoko had to pack up her kids and belongings by herself and for over a year at Poston, she rarely got word of how Shig was doing.

The volume of letters she wrote to him are now stored at the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies, now part of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and they are mentioned in the book “Since You Went Away: World War II Letters from American Women on the Home Front,” edited by Judy Barrett Litoff and David C. Smith (University Press of Kansas, 1991).

The Iwata family ended up going to the East Coast for work and spent the rest of their lives in Seabrook, New Jersey, working for Seabrook Farms in the frozen-food packaging plant. They had five children — Masahiro, Misao, Miki, Michi, and Misono; the Iwatas make up the largest number of F.M.’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren/extended family. Sonoko’s life story was written by her son-in-law, Roger Walck, Misao’s husband.

Two of F.M.’s great-granddaughters from Sonoko and Shig, Mia and Michele Suh, appear in the Fox 11 News Mira Costa High story. Michele married Suthern Hicks in 2016 with a ceremony/reception at the Boddy House in Descanso Gardens!

The remaining Uyematsu siblings, Francis, Marian, and Sam, spent their working lives running Star Nursery until it was sold in 1988. My sister Amy and I, daughters of Francis and Elsie, are the only West Coast grandchildren of F.M. Marian Naito is the last surviving child of F.M. She and her husband George Naito, along with Hideko “Miki” Uyematsu, Sam’s widow, are the remaining elders. Francis G. passed in 2003; Sam passed in 2011.

F.M. passed away in 1978 at the age of 97. He will be honored 40+ years after his death at Mira Costa High School, thanks to the efforts of Chuck Currier, former teacher who researched Mira Costa High’s history. The Manhattan Beach Unified School District will place a permanent marker in honor of FM Uyematsu at Mira Costa High School on October 30 at 9:30 am. You can watch the dedication ceremonry on zoom here.

* This article was originally published in The Rafu Shimpo on June 19, 2021.

© 2021 Mary Uyematsu Kao