On the night of September 11, 1966, the Sakura Maru that we were on dropped anchor in the port of Santos. The next morning, people began to bustle about and disembark. Unloading my luggage and immigration procedures were extremely slow, and my elderly "patron" (employer) husband and wife who came to pick me up had apparently been waiting since early morning, but it was dusk when the customs officials finished inspecting my luggage and we left Santos and headed into the interior.

The small Volkswagen "Fusca" (nicknamed "Stag Beetle") carrying the three of us climbed the mountain pass of the coastal mountains, the air-cooled engine humming with pleasure. After a while, the "Fusca" crossed the big city of São Paulo and entered the road to Ibiuna County. The winding road went up and up. On the way, we stopped the car next to a snack bar called a "bar" in the town of Cotia, which is located on a small hill.

The "patron" raised his hand and called out to someone in the back. A man with a small moustache came out and answered brusquely, "What?" Even though it was night, he was wearing a fedora. The "patron" stuck out four fingers and said, "Café ginho" (coffee).

There was a metal container resembling a water heater placed inside the counter. Next to it were square bathtubs filled with hot water. Steam was rising, so it must be hot. Chobihige dipped a small coffee bowl into the water in the bathtub, drained the water, and poured coffee from the water heater's tap. He placed a teacup on a small saucer on the counter and held it out to me first. "Here, have a drink," the old woman urged with a smile.

It has an indescribable aroma. It's so hot that it burns your skin when you take a sip. It's delicious when you blow on it to cool it down. It relaxes your body, which has been hunched up in the cold on the mountain. It's thick and sweet, but it warms your body.

Besides the "patron" and the old lady, there was another Brazilian. He was the driver of the Volkswagen "Kombi" (a type of small Volkswagen bus or station wagon) that was carrying my luggage. He was also wearing a hat. When the "patron" paid the money for all four of us, the little mustache smiled for the first time. He was very materialistic.

The Fusca, driven by Patron, makes an even more pleasant noise as it goes up and down the dark road. There are few cars passing by. After about 20 minutes of driving, we emerge from the darkness of the forest and emerge into a grassland where we can see the swaying city lights in the distance. Eventually, the car turns left and heads down the bumpy road. Dust rises from behind the Fusca and comes in through the window. The smell of red soil. Mixed in with the strong smell of grass. We go down and then up the narrow red soil path.

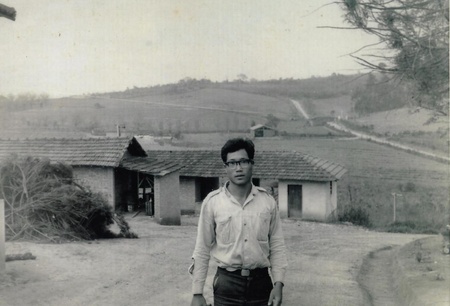

A light hanging from a nearby electric pole lit up the wooden fence. A middle-aged man came out and opened a wooden gate, the kind you often see in Western movies. After a 50-day voyage, I finally arrived at my assigned location, the M poultry farm. Next to the entrance was a small Japanese-style garden.

"Come on," the "patron" said, and ushered me into the reception room. I was told I could enter with my shoes on. After a quick greeting, I headed to the dining room, where a large, long table was set up. There, I was greeted by my nephew, who had opened the gate for me, his wife, and their four young daughters. There was a senior "young man named Kochia" who had been allocated to the fields like me, a young couple, and the family of a "Meia" (an independent farmer on a commission system), all of whom looked up at me, a "newcomer," curiously.

We toasted with beer and a soft drink called "guarana" and began our late dinner. In addition to sushi, sashimi, and simmered Japanese food, there were also some unusual dishes on the table. The smiling elderly couple all agreed, "Eat as much as you can." "Brazilian food is delicious once you get used to it," my nephew's wife said as she passed around the plates. We were asked about recent events in Japan, but everyone seemed to already know a lot about it. It was still early in the morning, so everyone got up and left. The four of us left at the table were the "patron couple," my nephew, and myself.

Stroking his gray hair, "Patron" talked about the hardships of his long life as an immigrant in Brazil. He is now the owner of a farm of "20 alqueres" (50 hectares). He repeated the same stories over and over, exuding the joy of success. Still, they were all rare stories for me, and I began to dream that I too could be successful and become a large farm owner someday.

Listening carefully, I noticed that "Patron" would repeatedly start a conversation with "we". "We"? I remembered a lord once used the phrase "I am satisfied", and wondered if success in Brazil would make it an arrogant way of saying things.

After a series of events, I left the chicken farm in Ibiuna and applied for a job at a Japanese fertilizer company in the big city of Sao Paulo. There, my co-workers would say things like "I don't know" or "I'll go too," and even Japanese people who weren't successful would use "I." So they refer to themselves or me as "I."

One day, I spoke to a Japanese university student who lived in the same boarding house as me, whom I rarely met. He understood Japanese well, so he spoke to me in Japanese. I tried speaking to him using the "yo" (I) that I had just learned. He immediately told me, "Stop saying "yo" (I)." He admonished me, saying, "That's why the Portuguese spoken by Japanese people sounds like a country language."

I (first person) is 'eu' in Portuguese. 'E' is pronounced strongly, and 'u' is pronounced softly, with just a light touch. Westerners move their jaws and tongues widely to pronounce 'aeiou' clearly. Japanese people, who do not move their mouths much, cannot pronounce 'aeiou' clearly. Because their jaws and tongues do not move smoothly, 'eu' is pronounced contracted and sounds like 'yo'. Brazil has a high rate of illiteracy, and most farm servants are illiterate. When they receive their daily wage, they put their thumbprint on the receipt.

Many of us Japanese immigrants do not go to school in Brazil. On the farms, we learn conversations between "patrons" and servants by ear, so we inevitably end up speaking rural dialect. The Japanese student who warned me was probably scolded by his teachers and friends for his "Portuguese pronunciation" when he started elementary school, and was teased by bad boys who said, "Hey, Japanese!" He was inspired and is now a student at a famous university in Sao Paulo. My wife has had the same experience, and I heard that people who do not speak English fluently are ridiculed in America as well. Of course, it's the same in Brazil. Now that I've immigrated to Brazil, I vow to study the basics of Portuguese.

© 2021 Maximiliano Shigeki Matsumura