After his stays in Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, and Cuba, Tsuguharu Foujita resumed his round-the-world tour. In November 1932, he arrived in Mexico City. As an international celebrity in the art world, he was already well-known to Mexican art lovers. As early as 1922, his work had been the subject of a feature article in the newspaper Excelsior, “Foujita, Un grande y extraño artista japones, muy apludido en Paris.” [Foujita, A great and strange Japanese artist, Greatly applauded in Paris].

Foujita originally intended to stay in Mexico City for only one month, and to visit with Diego Rivera, whom he had first met in Paris two decades previously, not long after his first arrival in the City of Light. In the event, he did not reconnect with Rivera, who was working on murals in the United States during early 1933 (notably the notorious and ultimately-destroyed mural that Rivera was commissioned to produce for Rockefeller Center in New York City).

Foujita nonetheless enjoyed himself so much in Mexico that he ended up spending seven months there. He found Mexico an inspiring place to work, and completed a large selection of canvases. In one later interview, Foujita claimed to have shot several reels of motion pictures in Mexico, and added that that he intended to use his sketches to illustrate a travel book by Madeleine (Mady).

During Foujita’s stay in Mexico City, forty of his paintings were displayed in a large-scale exhibition, while art collector Louis Eychenne organized two shows of Foujita’s drawings. The artist attended a Christmas reception at the French embassy, and was fêted at a gala reception hosted by Japan’s ambassador to Mexico, Yoshiatsu Hori, and attended by members of the US diplomatic corps. It is not clear how much Foujita connected with local Japanese during his stay—Mexico City was home to some celebrated individuals, including theater director Seki Sano and diplomat/professor Kinta Arai, but the region’s total Nikkei population was barely 1,000.

Foujita left Mexico City by train at the end of June 1933, and crossed into the United States. After stopovers in New Mexico and Arizona, he and Madeleine arrived in Los Angeles on July 5, 1933. Beyond the artist’s famous eccentric appearance, the couple made a strong visual impact. Interracial marriage was then illegal in California, and mixed-race couples were relatively rare (Ironically, the middle-aged Foujita and his much younger wife resembled many Issei couples in their respective ages). Foujita announced his plans to the press. “This is my first trip to Los Angeles and I am really delighted to be in such a refreshing climate. I intend to stay here for about two months, after which I will go to the South Sea islands following a brief visit to Japan. I am planning on painting the various Japanese that I find along this Pacific area.”

In mid-July, soon after Foujita’s arrival, the Dalzell-Hatfield Gallery opened a solo exhibition of 87 of his works, mostly produced during his Latin American trip. They included street scenes and portraits of indigenous people from Mexico and Bolivia, the inevitable pictures of cats, plus Japanese watercolors. Meanwhile a show of his Mexican landscapes, plus watercolors done on rice paper, was exhibited at the Art Gallery of the Palos Verdes Library. On August 3, Fujita’s show moved to the Illsley galleries at the Ambassador Hotel. It now included some 15 pieces done in California. On the exhibition’s opening day, Foujita gave the first of three special one-day courses to select groups of twenty students of the Art Center school, arranged through Nisei photographer Dave Kurakane. The next day, he held an informal reception and lecture before a group of 60 prominent Los Angeles artists and critics. The artist spoke in French on his theories of art and its present trends, and made several sketches.

Foujita’s stay in Los Angeles received daily coverage in the local Nisei press. The presence of such an international Nikkei celebrity in their orbit was thrilling for locals. Columnist Roku Sugahara pronounced in Kashu Mainichi:

“When the tumult and the shouting dies, the names of generals, potentates, and statesmen will soon be forgotten. But fine art lives on eternal. Maybe that’s why Tsuguharu Foujita has been acclaimed one of the greatest Japanese of the modern era….Lives of great men often remind us—and so do the lives of great artists. There is just that glamour and drama in the life of Foujita.”

In Kashu Mainichi editor Larry Tajiri reported on a visit from the artist:

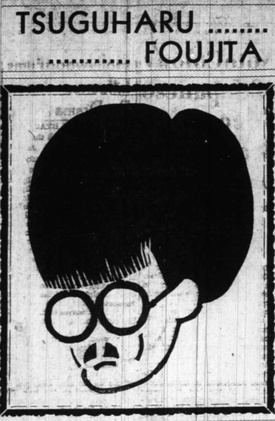

“We met Foujita yesterday when he came up to the editorial sanctum, and he didn't even vaguely resemble a cat. A wealth of grey-black hair, cut in distinct sharp style Foujita affects, and thin horn-rimmed glasses, represented this famous Parisian artist.”

Foujita, though he had worked with California artist Henry Sugimoto in France, was not greatly familiar with Japanese American life at the time of his stay in California. As can be inferred from his initial comments about doing paintings of local Japanese, Foujita may have hoped to find subjects and/or patrons in Little Tokyo, and he made efforts to reach out. Leaders of the Japanese community were invited to his gallery show openings.

In late July, he spoke at a round-table on art at the Olympic Hotel, near Little Tokyo. At the request of the Kumamoto kenjinkai and Tokyo prefectural clubs, he agreed to mount a downtown exhibition especially for the Japanese community. The exhibition opened in a hotel room at the Olympic Hotel on August 24, 1933 and ran for four days. Foujita also agreed to visit the Japanese Amateur Photographers club on August 31 and to review their work. Sadly, like the larger visit, these efforts were generally unavailing. In October 1933 Larry Tajiri wrote in Kashu Mainichi, “We know that Foujita, the internationally-famous Japanese painter, was disappointed by the lack of enthusiasm in the Los Angeles reception. Paris, Buenos Aires, or Rio was never like this. [There] veritable reams of copy were written of Foujita, his wife, and his cats. In Los Angeles he elicited little response in comparison.”

In September 1933, Foujita left for San Francisco. As in Los Angeles, his name and his work were already known. Indeed, just one year before, some Foujita works had been included in a show of modern Japanese prints at the city’s De Young Museum. A review in the Oakland Tribune lauded the works. “It would be safe to say that the average Occidental could not date these within a hundred years if it were not for Foujita. This fellow and his cats are modern revolutionaries to Japan. He chooses western subjects and does them in Japanese.”

Foujita’s appearance in San Francisco was highlighted by a three-week show at the Courvoisier Gallery, which combined his Latin American works with a separate room of Parisian nudes. The opening was not without a dramatic flair. According to one report, on the weekend before the show’s Monday premiere, neither the artist nor his pictures had arrived, so gallery owner Guthrie Courvoisier took a night plane to Los Angeles, bundled Foujita and some of his pictures into the return flight, and landed just in time to hang them for the opening. Several days later Foujita returned to Los Angeles to pick up Madeleine and take her to San Francisco with the remainder of his baggage.

The Courvoisier gallery show was a success, and was held over for a fourth week.

In an article in the Oakland Tribune (which featured the trenchant subheadline, “Nudes, Peons and Cats Vie for Interest in S. F. Gallery Display”) critic H.L. Dungan noted, “Foujita has used more color in most of his Mexican pictures then in his French. There are portraits or full length figures of men and women. He has departed from the Rivera-Orozco tradition that all Mexicans must appear in a paint[ing] as solid as board, clothes and all. He has given the Mexican the lightness of the Japanese touch without depriving him of his character or characteristics.” Foujita was fêted by local artists and intellectuals. In October he spoke before the city’s elite Commonwealth Club.

As in Los Angeles, Foujita’s tour was heavily covered by the local Nisei press. However, whether because he already knew individuals such as Henry Sugimoto or just because Bay Area Nikkei were generally more sophisticated, Foujita seems to had an easier time connecting with the community than in Little Tokyo. He was the guest of honor at a sukiyaki party at the Yamato hotel in September. Shin Sekai journalist Wally Shibata described the visitor positively: “Individual. Intensely so, yet contrary to general expectations, he is not eccentric. Confident, yet unassuming…interesting, cosmopolitan, and possessor of a whimsical sense of humor, [he] proves to be a regular fellow.”

Shibata recounted being invited by Henry Sugimoto to join him and the Foujitas on a trip to Golden Gate Park. Foujita was enchanted by the Japanese Tea Garden, which made him homesick. When they went to the Park’s aquarium to view the fish, the artist himself drew a crowd. “Always an object of attention in a crowd, many of whom evidently recognize Foujita, for his tortoise-shell rimmed glasses and the bangs are conspicuous badges of individuality, he is sometimes just a little weary, perhaps, to be an eternal cynosure. But he wears his mantle of fame modestly, graciously. The applause has not lessened his interest in his fellow human beings, nor in the world in general. Perhaps that is the reason why, despite his graying hairs, his spirit seems very young. ‘Au revoir,’ said Foujita in French to us as we parted. ‘Sayonara’, said his wife in Japanese.”

Tsuguharu and Madeleine Foujita sailed to Japan in November 1933. Madeleine died in Japan three years later. In 1939, Foujita traveled once more to Paris, but soon returned to Japan. There he abandoned his established artistic style and began a series of brutally heroic war paintings. In 1938 the Imperial Navy Information Office supported his visit to China as an official war artist. After Pearl Harbor, he lent his artistry to supporting Japan’s war effort against the Allies in World War II. His monumental painting Final Fighting at Attu (1943) depicts gallant Japanese soldiers in a final stand against US forces. Similarly, Compatriots on Saipan Island Remain Faithful to the End (1945) glorifies the mass suicide by Japanese soldiers and civilians following the American invasion of the Pacific island.

Following the end of the war, Foujita was publicly denounced in Japan due to his propaganda works. (Ironically, under the American occupation, a set of his wartime paintings was seized by the United States government, which later offered them on “indefinite loan” to the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo). With his reputation permanently stained in Japan, in 1949 Foujita left his native land for the last time, accompanied by his Japanese wife Kimiyo. On the invitation of General Douglas MacArthur, the American proconsul, he traveled to New York, where he worked for a year. When he planned an exhibition of his works, Yasuo Kuniyoshi opposed the holding of the show, labelling Foujita a fascist and imperialist.

In 1950 Foujita returned to France. Apart from his brief visit in 1939, he had been away for nearly 20 years. There he worked once again to reinvent himself. In 1955 he became a French citizen, taking the Western name Léonard Foujita (in honor of Leonardo da Vinci). Two years later was awarded the Legion of Honor by the French government. He took up residence in Villiers-le-Bâcle, a town southwest of Paris. Under the sponsorship of René Lalou, director of Mumm’s champagne, he converted to Catholicism, and shifted his focus to religious art. He devoted much of his attention in his last years to designing a chapel in Reims and producing stained glass and frescos for it. The Chapel of Our Lady Queen of Peace (better known as the Foujita Chapel) was completed in 1966, two years before his death in Switzerland.

© 2021 Greg Robinson & Seth Jacobowitz