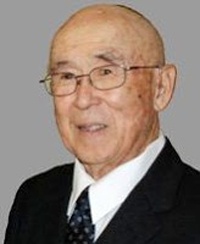

The life of Kenji Murase, a Nisei litterateur, activist, and social scientist, illustrates some of the challenges faced by Nisei intellectuals in the mid-twentieth century. Although he came from a poor farming family, and had to scramble to get an education, Murase threw himself into progressive literary and political movements. Years later, even after he became a distinguished professor, he retained his focus on community empowerment.

Kenji Kenneth Murase was born in Parlier, California, near Fresno, in January 1920 (while his birth and marriage certificates listed January 9 as his date of birth, Murase claimed January 3 as his birthday). Known in his youth as “Kenny,” he was the second of three sons of Mantsuchi (AKA Manzuchi) and Moto Murase, Japanese immigrants who eked out a living as sharecroppers working in the grape fields. According to the later testimony of his daughter Emily Murase, the family had so little money that they made clothing at home, sewing shirts from rice sacks. Murase attended Parlier Union High School, where he joined the track and basketball teams. He graduated in 1938 as co-valedictorian. During his teen years, he became interested in writing, and published an essay in the Scholastic magazine.

Murase later recounted that he did not go directly to college after graduating high school, due to family opposition and financial concerns. Instead, he worked as a farm laborer during the day and wrote in the evening. During this time, he made contacts with Nisei in Los Angeles, and soon started working as a columnist and fiction writer for the local Nisei press. In June 1939, he published a short story, “Resurrection,” in Kashu Mainichi. It was the tale of a Nisei, embittered by prejudice, who is shocked to discover the more severe discrimination faced by African Americans. He followed that in October 1939 with “Gummed Up,” a baseball story, and in December 1939 with a satirical romance, entitled “By the Time You Read This.” At the same time, he began a regular column for Kashu Mainichi, which he dubbed “Perpetual Notion.” In its pages he engaged in a mock-feud with “Napoleon,” his friend and fellow columnist Hisaye Yamamoto, who blasted Murase as a pimply-faced stuffed shirt. The young Kenny also contributed to the 1940 new year issue of Nichi Bei a short story about Nisei farmers (around that time, the Murase family bought their own farm, near Reedley, California, and relocated there).

By the beginning of 1940, Kenny Murase enrolled at UCLA. During this period, he expanded his press activity. He penned a short story, “That Old Indian Summer,” for Rafu Shimpo, wrote a regular column for the short-lived Nisei newspaper Japanese American Mirror, and in November 1940 began a new column for Nichi Bei, (first called “Nocturne” and later “The Sixth Column”). He likewise contributed extended articles to James Omura’s monthly magazine Current Life. Murase’s piece in the October 1940 issue of Current Life, "Who's Who in the Nisei Literary World," was a jokey guide to the circles of West Coast Japanese American litterateurs. For example, he described his close friend and fellow progressive activist Warren Tsuneishi as “an ultra-reactionary and rugged individualist (weak emphasis on “rugged”) [who] adores girls with ‘exquisite lips.’” In the issues of Current Life that followed, he produced an analysis of the work of popular Armenian-American author William Saroyan, whom he claimed as a model for second-generation creative artists.

Even as he threw himself into literature, Kenny Murase became absorbed in progressive politics, and he connected his creative vision with his commitment to racial equality. In November 1940, the Fresno Bee published his letter scoring racial discrimination against the “American-born Japanese.” In the letter, he contended that “American society has failed to function properly in relation to its diverse racial elements” because of the general tendency by hostile whites to assume that those of foreign ancestry were attached to their ancestral nations. Murase countered that the Nisei were loyal to the United States, and as supporters of democracy. “[We] cannot accept the totalitarianism which is rampant in the country of our ancestors. We recognize the war in China for what it is, an imperialistic war of aggression, and we will have none of it.” In a period when the Nikkei press generally either supported Japanese foreign policy or remained silent, this was a powerful statement of opposition.

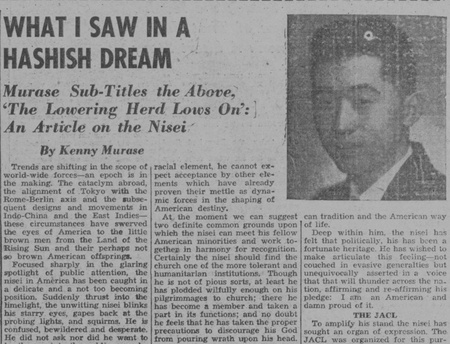

Even as he defended the American-born Japanese to outsiders, Kenny Murase addressed his fellow Nisei. In several articles, he hammered home the theme of the responsibility of Nisei writers to use their words so as to offer leadership to the rest of the community, even as writers from other racial/ethnic groups had done, and to win Japanese Americans outside recognition as a dynamic minority. For the new year 1941 issue of Nichi Bei, he penned a column with a daring title, “What I Saw in a Hashish Dream.” It was a frank exploration of the plight of the Nisei, one that reflected his growing political awareness. In it, he excoriated the Nisei for their insularity and stifling group consciousness.

“The immediate security and congenial relations that [the nisei] has found among his fellow nisei has perhaps satisfied him; but at the same time, it has built around him an impenetrable shell of indifference to the existence of other racial minorities and their problems which are not exactly diametrically opposite. As long as the nisei insists… upon clinging to the myopic viewpoint of working only among his own group and ignoring the Italians, Poles, Jews, Chinese, Negroes, and other minorities, his will be a lonely and a futile cry in the vast wilderness of apathy and scorn.” The solution, he contended, lay in organizing through churches and in political action. Murase respectfully critiqued the JACL, which he found too patriotic and insufficiently focused on intergroup action. “We have known JACL workers to be earnest, conscientious, and unquestionably sincere; but at the same time, we have also known JACL leaders to be opportunists and lacking in a clarity of vision. It is not in them wholly, however, that the ailment of the JACL lies; it is in their program that we find inadequacy and misdirection.”

In 1941, Kenny Murase enrolled at UC Berkeley as an English major. As a result, he scaled back his writing for the daily Nisei press, though he continued to contribute to Current Life. He rapidly joined assorted progressive on-campus clubs such as the Welfare Council of the Associated Students of the University of California, and was named to the executive committee of the local Y.M.C.A. Race Relations group. Around this time, Murase joined the Nisei Young Democrats of Oakland, and was named their Educational Chairman. Through the Nisei Young Democrats, he collaborated actively with African American attorney Walter Gordon in his campaign against restrictive covenants in the East Bay that limited housing opportunities for minorities.

Because of his literary flair and progressive political interests, Murase became a point man connecting Nisei outsiders on campus. Murase grew especially close with James Sakoda, then a graduate student, and the two moved in together into a shack in Berkeley. He soon also connected with other socially-minded Nisei such as Tamotsu Shibutani, Warren Tsuneishi and Charles Kikuchi. In fall 1941 Kikuchi collaborated with Murase on a review of Louis Adamic’s book Two Way Passage for Rafu Shimpo, and the two friends led a symposium in Berkeley on Nisei and Labor. Murase moderated the meeting, and Kikuchi presented the findings of his survey of Nisei employment.

Following the Pearl Harbor attack and the outbreak of the Pacific War, Kenny Murase was invited to join the Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy (NWAMD). On behalf of the NWAMD he wrote a column for Nichi Bei in March 1942 expressing his frustration with anti-Nisei discrimination and impending mass removal, which was occurring because, he said, “our folks are considered in the camp of the enemy and the Army can’t afford to take chance with us.” However, he reminded his readers that in an Axis country they risked being sent to real concentration camps. He further suggested that the wartime events had an unexpected benefit in permitting the Nisei to emancipate themselves at a single stroke from the Issei leadership, which had delayed their entry into the American social and economic mainstream. The Nisei, he proclaimed, should look beyond their personal interest and join the struggle to destroy the Axis powers.

As mass removal turned into mass confinement, however, Murase’s resentment over the injustice to the group mounted. In a letter to author Carey McWillliams, he noted, "We are not going to camp because of 'military necessity.' We know that such a reason is groundless. We are going because groups of native American fascists were able to mislead an uninformed American public, and this partly because we were uninformed and unaware of our responsibility as one integral part of the democratic process." During early 1942, he published a pair of letters in the Fresno Bee defending the Americanism of the Nisei (and immigrants generally) against racist attacks on their loyalty.

Sometime before the end of the Spring 1942 term, Murase left Berkeley and returned to his family farm in Reedley. Reedley lay in Military Area 2, outside of the main West Coast excluded zone, so the Murase family was not taken away to the Assembly Centers during Spring 1942. Because of his interest in race relations, Murase applied to transfer to Howard University, an African American university in Washington DC. He had no money for his studies, so he also applied for a scholarship. Howard officials failed to act on his request. Their official reason was that they were not certain whether Nisei students could be admitted into the East Coast Defense zone. It seems plausible, however, that they also failed to act because they were less than enthusiastic about admitting a Japanese American in the face of widespread prejudice against them. Even after the West Coast Defense Command announced that, contrary to their previous promise, Military Area 2 would be emptied of its ethnic Japanese population, Murase hoped to move out and continue his education. Murase was invited to join an interracial work camp in Dearborn, Michigan, and applied to the Army Provost Marshal’s office for permission to leave, but he was turned down. Facing confinement, Murase applied to go to Tule Lake, where he could join the Japanese Evacuation Research Survey (JERS) project there. However, the authorities sent him to the Poston camp.

© 2020 Greg Robinson