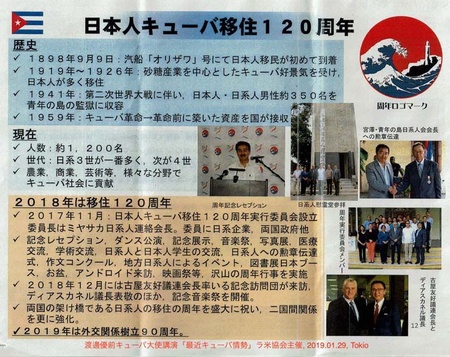

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Latin America and Caribbean Affairs Bureau also conducted a survey of the Japanese community in Cuba from October to November 2018. The year 2018, when the survey was conducted, marked the 120th anniversary of Japanese immigration to Cuba, and various commemorative events were held in the capital, Havana, sponsored by the Japanese Embassy and other organizations. It may be surprising, but Japanese immigrants have a longer history than those who immigrated to Peru or Brazil. And 2019 marked the 90th anniversary of the establishment of amity between Japan and Cuba. The total number of Japanese immigrants in Cuba today is about 1,200. There are several documents in Spanish and Japanese about Japanese immigrants1 , but little is known about the current state of the Japanese community. Therefore, it is very significant that Cuba was the target country for this survey, and it is believed that the results will be useful for future JICA projects and cooperation between the two countries2. This time, we will report on the survey results.

114 survey participants

A questionnaire survey was conducted in October and November 2018 targeting Japanese people throughout the country. A total of 114 questionnaires were returned, including 33 in the capital Havana, 11 in Juventud Island, 12 in Pinar del Rio, 11 in Cienfuegos, 9 in Camagüey, 11 in Mayabeque, 9 in Holguin, 8 in Ciego del Avila, and 7 in Santiago de Cuba. Currently, the largest population of Japanese people is in the capital Havana, but they are scattered throughout the country3 . This is related to the fact that many Japanese people were imprisoned on Juventud Island during the war4 . After the war, some returned to their original residences, but they moved to other areas. In addition, there is a Japanese Association on Juventud Island and a liaison group in Havana5, but there are no Japanese organizations in other areas. Despite this, we would like to express our respect for the coordination skills and effort of the Japanese leaders who visited areas where Japanese people live in Cuba, where the transportation and communications infrastructure is not well developed, and collected responses from nearly 10% of the Japanese population.

In terms of generation, 49 respondents (43%) were third-generation Japanese, and 55 respondents (48%) were fourth-generation Japanese. In terms of age, 63% were in their 20s and 30s, and 35% were in their 40s. By gender, 40% were male and 60% were female. In terms of marital status, 48% were single, 35% were married, and 10% were separated or divorced. 58% reported having children. In terms of educational background, 77 respondents (67%) had graduated from university, 40 had received specialized training, and 6 had obtained a graduate degree.

Japanese ties and identity

Overall, 60% of respondents said they have relatives in Japan or know of their existence, but 14% said they do not have any relatives, and 18% said they do not know whether they have relatives or not. Perhaps because of the large language barrier, it seems that by the fourth generation, contact with Japan has been cut off and people no longer know whether they have relatives or not.

When asked about the prefectures where their ancestors came from, many people said Kumamoto, Okinawa, Hiroshima, etc., with some also saying Fukushima, Shizuoka, and Kagoshima. However, many people did not answer (35% on the father's side, 42% on the mother's side), which shows that many people do not know the prefectures where their ancestors came from. Also, since there are only a few households of Japanese descent in rural areas, these figures seem to reflect the fact that not only the Japanese language but also Japanese customs and records of immigrants are not being properly passed down.

However, it is interesting to note that approximately 80% answered that they have a strong sense of Japanese identity, 17% answered that they have some sense of Japanese identity, and only four people (4%) answered that they have no sense of Japanese identity at all.

Experience in Japan

Regarding their experience visiting Japan, three people answered that they had been there as JICA trainees. In recent years, Japanese Cubans have been seen not only in the JICA trainee program, but also among participants in the Japanese government's JUNTOS and the Next Generation Japanese Leaders Invitation Program. However, 96% of the total (110 people) answered that they had no experience working in Japan, showing that the country's system and regulations are a major obstacle to studying or working abroad6. Only 12% (14 people) answered that they had actually visited Japan, and of these, more than 90% were Japanese people living in Havana. The reasons for visiting Japan were to visit relatives ( 5 people), to study abroad (3 people), and for JUNTOS (1 person), and most of the stays were less than one month.

Interest in Japan

For third and fourth generation Japanese, the proportion of mixed races is high, and opportunities to learn Japanese language and to come into contact with Japanese culture and customs are quite limited. Therefore, even for Japanese people, rather than inheriting Japanese culture from their parents, they often learn from manga, anime, movies, magazines, and books, just like local non-Japanese people.

The things they were interested in about Japan were, in order, Japanese pop culture, traditional culture, Japanese food, teamwork, technology, organization and discipline, etc. On the other hand, when asked about things they didn't like about Japan, they mentioned things like not knowing much about Japanese people, lack of emotion, cold human relationships, being somewhat closed off, and strict regulations and inflexibility.

Overall, people want to know more about Japan, and some called for training programs and exchange programs with young people in Japan, as well as the desire to learn more about Japanese people in their own countries. However, there are few people who can teach Japanese, so private lessons are expensive and there are very few opportunities to learn Japanese. Also, since it is not possible to take the Japanese Language Proficiency Test in Cuba, it can be said that motivation to learn Japanese is not very high.

Japanese culture related projects

Regarding events planned and promoted by the Japanese Embassy, information has become much more accessible to local Nikkei people in recent years, so half of the survey respondents said they were aware of them. Looking at Facebook, photos of events organized by the Embassy are often shared, and it seems that Nikkei people are showing an increasing interest in Japanese cultural events7 . In terms of event participation rates, about 30% of respondents said they always participate, and if those who said they sometimes participate are included, the total number of people is 46, meaning that nearly half of the survey respondents have participated. However, this is limited to urban areas, and it seems that migration from rural areas is an issue that is preventing an increase in participants. On the other hand, when it comes to involvement with the local community, about 30% of the total participate in industry and professional associations and local volunteer activities.

Cuba's Japanese people each have various requests and proposals, but to realize them, organizational strength and financial resources are required. However, the most important thing in this country is to establish an information transmission network. Although mobile phones are widespread, high-performance devices such as smartphones are not widely used, and the Internet environment is also inadequate. However, there is a small personal network of Japanese people who have come to Japan for JICA training and other events, and they act as leaders in the community and transmit information within the community. In fact, it was thanks to their personal networks that we were able to obtain a large amount of survey data in this study, which allowed them to travel around the country and call for participation in the survey. There is no doubt that such networks will continue to play a major role in the future as a means of community cooperation.

lastly

The Japanese people in Cuba have a completely different history and live in a different environment than the Japanese people in Latin America. However, we understand very little about their history or current situation. Learning more about them would not only be a good stimulus for us, but it would also be necessary for us to deepen our exchanges with them across borders, foster friendships, and build cooperative relationships in the future. To that end, since the Japanese people in Cuba cannot travel freely abroad, it would be good for us to visit Cuba. We would like to make such an appeal in the future.

Notes:

1. Rolando Alvarez Estevez and Marta Guzman Pascual, co-authored, translated by Nishizaki Yasuko, "Cuba and Japan: The Unknown Footprints of Japanese-Brazilians," Sairyusha, 2018. A Spanish version was published in Havana in 2002 with the support of the Japan Foundation under the title "Japoneses en Cuba" (published by Fundación Fernando Ortiz).

2. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Latin America and Caribbean Affairs Bureau website, summary of survey results: https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/la_c/sa/page22_003192.html

Summary translation of Spanish: https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000496404.pdf

3. In Cuba, a socialist country, moving or changing jobs requires very cumbersome procedures and people are not able to move freely.

4. During the war, 350 Japanese and several second-generation Japanese were incarcerated as enemy aliens in the Model Prison on Isla de la Juventud (then called Isla de los Pinos, "Island of Pine Trees") for three years and several months.

5. The chairman of the Liaison Council of Japanese Organizations is Francisco Miyasaka, a second-generation Japanese American and one of the leading figures in the Japanese community.

6. Cuba has a low income, making it difficult for ordinary citizens to travel abroad. They need an exit permit from the authorities. There have also been reports of people being denied departure at the airport even if they met all the requirements.

7. In Cuba, it is not easy for ordinary citizens to open a Facebook account. People who work for foreign companies can open an account relatively easily, but they usually open an account when they go abroad or ask a relative abroad to open one for them.

© 2020 Alberto Matsumoto