In 2012, historian John W. Dower published a book with various essays on the history and relations between the United States and Japan. The writings in this book were already widely known and were grouped under the title Ways to forget, ways to remember. Japan in the modern world . 1 The name of the book was not anecdotal or casual but had the purpose of making readers reflect on how the history and events of countries can be used in various senses and objectives “to educate or to indoctrinate, consciously or subjective, idealistic or perverse.”

The reflections in Dower's book allow us to shed light on how the history of the persecution and concentration of Japanese immigrants in America is used with various intentions. Let's see some examples of this.

In the first days of May, faced with the pandemic caused by the coronavirus in the United States, the health authorities and the governor of the state of Wisconsin, Tony Evers, decreed a series of measures that isolated the population and temporarily suspended activities. non-essential economic measures with the purpose of preventing infections from expanding exponentially.

A group of Republican congressmen, opponents of Governor Evers' measures, promoted before the Court of Justice resources that would reverse the health policies of social distancing. The judge, Rebbeca Bradley, echoing the purposes of the legislators, described the population isolation measures as “tyrannical.” The judge also equated the policy of protecting the population due to the pandemic with the massive concentration of American citizens of Japanese origin that was decreed in 1942. To support her argument, Judge Bradley mentioned the trial filed by the young American Fred Korematsu against the State in that year to avoid being forced to remain in one of the ten concentration camps that the authorities built to imprison 120 thousand people of Japanese origin, two thirds of them American citizens.

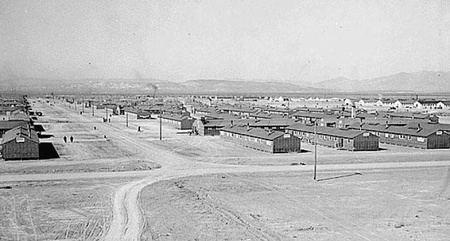

Let us briefly remember the events that Korematsu faced at the time when the war broke out and the concentration of the Japanese communities was decreed in the month of February 1942. At that time, the 22-year-old young man had already made the decision to not comply with this measure and not accompany his parents and three brothers who were transferred to the Topaz concentration camp, in the state of Utah. Given his refusal, the police arrested him and he was imprisoned in the month of May, a measure that Korematsu considered illegal, so he appealed to the judge to reverse it. His case, along with that of three other people (Yasui, Hirabayashi and Endo) who had not obeyed the confinement order, would reach the Supreme Court in response to the legal appeals that his defense lawyers promoted.

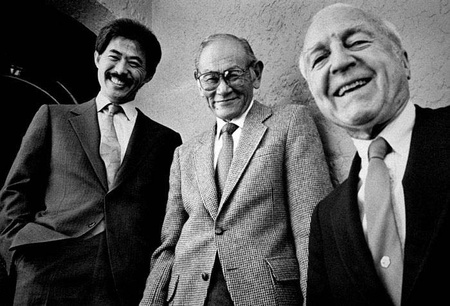

In December 1944 the Court finally rejected, by six votes to three, the arguments of Korematsu's defense. However, thanks to the arguments of the judges who opposed the ruling, it became clear that the conviction remained “in the disturbing abyss of racism.” In the 1980s, given the violations and lies that were observed in the process of these trials during the war, the survivors managed to open them again, a process that this time favored the complainants.

Justice was present after 40 years as the Supreme Court recognized that racial prejudices and the hysteria generated by the war were the elements that unjustifiably determined the imprisonment of tens of thousands of people. Congress consequently approved the Civil Liberties Act in 1988 through which American citizens of Japanese origin received an official apology from the State and compensation of 20 thousand dollars for the violation of their rights. In 1999, due to his fight to preserve civil rights, Korematsu received from President Bill Clinton the highest civilian decoration awarded by the government: the Presidential Medal for Freedom.

Therefore, comparing the concentration of citizens of Japanese origin and the Korematsu trial with the measures that aim to protect the health of all citizens in the face of the coronavirus pandemic is not only wrong but biased. Actor George Takei, who as a child was sent with his parents to a concentration camp, snidely criticized that comparison by reminding Judge Bradley in a tweet: “I'm at home watching Netflix. It is not a concentration camp, believe me.”

The other case that is worth remembering, to understand how attempts have been made to use the history of Japanese immigrants, happened four years ago. At the beginning of 2017, President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 13769, which severely restricted the entry of citizens from seven countries with Muslim populations into the United States. The decree prevented a large number of residents of those countries from taking refuge in the United States or even from entering many of them who already lived in this country and were abroad at that time. The restrictive measures to prevent access to the United States and the creation of possible lists that were intended to be used to register citizens who came from those countries, once again brought to light the unfair laws and regulations to which Japanese immigrants were subject given which it was pointed out could be used again.

The first voices against these persecutory and racist measures were those of the Japanese-American community. With great clarity and determination, some of them who survived the concentration camps expressed their rejection and the use of their history to launch searches and raids against Muslim-American communities. Chiyoko Omachi, 90, who had been sent to the concentration camp in Poston, Arizona when she was only 15 years old, called for the “hysteria” against citizens of Japanese origin not to be repeated. in the case of citizens who practice the Muslim religion. 2

Jim Matsuoka, 80 years old, was part of the contingent that in December 2016, in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of the city of Los Angeles, protested against the idea of registering or, worse yet, concentrating citizens. Americans from the Muslim community. Matsuoka considered that citizens who practice the Muslim religion were “welcome.” When he was a child, he was sent with his family to the Manzanar concentration camp, for which he noted with great sadness that at that time there was strong racism that unfortunately continued to be reproduced in the United States. 3

Remembering the history of immigrants and those who were victims of persecution due to their ethnic origin becomes a powerful weapon against hate speech, racism and xenophobia. Keeping in mind Korematsu's words that no citizen should be persecuted for their appearance as he experienced allows us to understand that the sacrifices and experiences of previous generations make sense to build a tolerant world. Memory, if used in a good way, can become the best vaccine against the virus of racism and persecution.

Grades:

1. John W. Dower, Ways of forgetting, ways of remembering . Japan in the Modern World, New York, The New Pres, 2012.

2. “We Interned Japanese-Americans - Are Muslims Next? Local Groups Fear Future”, Ted Cox, December 7, 2016.

3. “Japanese-Americans stand with Muslims in wake of attacks,” Josie Huang, KPCC, December 8, 2016.

© 2020 Sergio Hernández Galindo