Urban Ministry

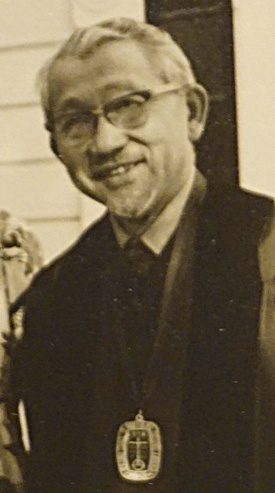

In 1965, United Church of Christ's officials in Seattle launched an experimental “Ecumenical Metropolitan Ministry” to focus on complex problems like poverty, racism and drug abuse. “We want to ask you to move from the campus to the city and become a metropolitan minister for the city,” Katagiri remembered his UCC superiors telling him when they recruited him to become the Metropolitan Ministry’s first staff person.1

To prepare him for his new job, UCC leaders sent Katagiri to Chicago in January 1965 for a month-long training, which included living on the frigid city streets for three days with only the meager clothes on his back and $2 a day. The 45-year-old minister dodged rats in empty lots, experienced disdain from fellow Japanese Americans, and learned how best to fill his stomach on little money. But he also received kindness: a place to sleep from a stranger and advice from another homeless street denizen.

Upon returning to Seattle, Katagiri recognized that most Christian churches were ill-equipped to deal with the multifaceted issues of urban life, from the population boom and a changing economy, to political and racial crises. He envisioned the major objective of his Metropolitan Ministry would be to “implement the work and witness of the Church in the economic, social, and cultural life of the community.” That did not mean dictating pious instructions to the poor and oppressed to repent from sin. Rather, Katagiri considered his work to be “a listening, relational, interpretive and witnessing ministry” partnering with social institutions, government agencies, political groups, labor unions and others to tackle the significant issues of city life.2

Advocacy for Gay Acceptance

Through his urban ministry, Katagiri met gay men who congregated in Seattle’s Pioneer Square, which in the mid-1960s was the site of bars and restaurants catering to gay people. One of the men was Nicholas Heer, a professor who had recently left Harvard to accept a position with the University of Washington’s Near Eastern Studies Department. Heer had been involved in nascent gay rights groups on the East Coast.

Heer and a small cadre of gay men had met in December 1965 at the Roosevelt Hotel in downtown Seattle at the invitation of Hal Call, leader of the San Francisco-based Mattachine Society, the first organization in the U.S. to advocate for gay rights. Following that gathering, Heer and others met in Katagiri’s office in the basement of St. Mark’s Cathedral on Capitol Hill in March 1966. That meeting resulted in the formation of the Dorian Society, Seattle’s first gay rights organization. For the first year of the group’s existence, members met in Katagiri’s office and at homes on Capitol Hill.

In late November 1966, the Seattle City Council was considering whether gay people had a right to public association, specifically in gay clubs and bars.

Few gay men and lesbians at the time publicly identified themselves as homosexuals. Doing so could result in firings, social ostracism and violence. So, when the city’s gay community needed a spokesperson to advocate for gay people’s rights during a contentious city council meeting about closing the city’s gay bars, Katagiri stepped up.

Katagiri was one of several Christian ministers in attendance, including the Rev. Thomas Miller of the Calvary Bible Presbyterian Church, who advocated that the council not permit gay people to congregate in bars because it “is the worst thing you can do for them—it simply encourages them.”3

Katagiri countered his colleague. Although there is no record of his statement to the city council, a subsequent letter he sent to Seattle’s mayor most likely conveys what he shared during the meeting. In his letter, Katagiri wrote, “The problem is twofold: society needs to learn to accept homosexuals as legitimate members of the community and homosexuals must learn to behave as responsible members of a larger community.” He warned the mayor: “Any action which can be interpreted as persecution will make the task of integration more difficult. The proposed closing of the bars only says to the homosexuals that the official policy of Seattle is one of persecution.”4

City officials ultimately allowed the bars to remain open.

Katagiri’s advocacy on behalf of gay people went beyond the city’s politicians to a constituency closer to home: church members and fellow clergy. In the mid-1960s, Katagiri organized a day-long meeting of gay people and clergy of different denominations. Ministers in other regions of the country had organized similar gatherings with gay people during that period. Katagiri, though, anticipated friction between the two groups. “I really thought this would be an area where we would have trouble,” the activist minister later told a reporter. But his fears were unfounded. “The fact is, many homosexual kids and adults come out of our churches,” Katagiri explained. “So, on the grassroots level, instead of getting condemnation, we got words of appreciation from church members who said, ‘Thank God there’s somebody trying to help.’”5

Katagiri also served as the gay community’s ambassador with Seattle’s newspaper reporters. He organized a “tour of night life in the ‘gay joints’” for local reporters so that gay people would “no longer become sheer statistics but real persons” to the journalists. Katagiri hoped that if reporters wrote about the gay community, they would not resort to sensationalism but rather adopt a sympathetic approach.6

Katagiri’s empathy with gay people was deeply-rooted in his belief in the dignity of every individual and his vision that all people have the opportunity to live with integrity and authenticity. He wrote of the gay people he knew in Seattle, “They feel deeply the fact that they cannot live openly and honestly as homosexuals. To live under a constant threat of exposure, loss of jobs, blackmail, ostracism is no life at all. What the vast majority of homosexuals basically desire is a chance at living honest and open lives. This, I think, they deserve to have.”7

Later Life

Katagiri’s activism was not limited to Seattle’s gay community. He worked on behalf of low-income residents, founding one of Seattle’s first organizations providing services and job training for Skid Row residents. He advocated for the city’s Black population, serving as President of the Seattle-King County Economic Opportunity Board and as a board member of the Central Area Civil Rights Committee and the Seattle Urban League. He also was a leader in Seattle’s budding Asian American civil rights community, serving as Chair of the Asian Coalition for Equality.

While working on behalf of specific communities, Katagiri never lost sight of the ways in which communities are interrelated. He was especially concerned about those he considered the “disinherited of our culture.”

In April 1965, he read a speech on Seattle’s commercial-free, listener-supported radio station KRAB. He explained that “the Negro, the poor, the Indian, the Skid Rod habitué, the welfare and ADC recipients, the homosexuals, are without real voice or power. . . . They are forced to live on the margin of life and are not given the opportunity to live in the meaning-giving centers of life. In other words, our attitude is: we don’t want them, but since we have them, we have to tolerate them. Make the best of a bad situation. Provide them with the minimum needs and try to forget them. Life is never that simple, and the health of a city will depend on how it deals with its disinherited population. . . . The hope lies in their capacity to gain sufficient power to speak on their own behalf.”8 Although he did not explicitly reference a Biblical basis for his sentiments, Katagiri echoed Christ’s instruction that to the extent we feed the hungry, welcome the stranger, clothe the naked, and visit the poor and ill -- treating those who are the “least” among us with dignity – we are doing the same to Jesus (Matthew 25:35-40).

In 1970, Katagiri left Seattle for New York to become the United Church of Christ’s Director of Mission Priorities. Between 1975 and 1984, when he retired, Katagiri was UCC’s Conference Minister of Northern California, a position similar to that of Bishop in other denominations.

Athletic into his senior years, he died in 2005, at age 86, from injuries suffered from a fall while golfing.

Next Generations

Other Nikkei clergy have followed the path that Katagiri blazed in advocating for the dignity of gay people. In 1971, Lloyd Wake, a Nisei minister at San Francisco’s Glide Memorial Church, generated controversy within the United Methodist Church after a journalist reported that the Japanese American clergyman officiated a commitment ceremony for two gay men.

Wake articulated a similar theology to Katagiri in explaining his ministry: “The only criterion for action is love. . . . The love I am talking about is not a romantic love; it is a love that very often takes sides, that takes the side of the oppressed. It is a love that tears down evil systems so that it can build up people who have been dominated by and dehumanized by those systems.”9

More recently, Rev. John Oda and Rev. Kevin Doi have taken the baton that Katagiri and Wake carried. Doi, who was the founding pastor of Epic Church in the Orange County community of Fullerton, had preached about embracing gay people since the Asian American congregation’s founding in 1998. But it wasn’t until a beloved church member came out several years later that Doi formed a deeper theological grounding for why Christians should welcome LGBTQ+ people.

Rather than considering as guideposts the Old and New Testament verses that conservative Christians cite when condemning homosexuality, Doi looked beyond what he considers those culturally-bound, disputable Biblical passages. “The gospel follows a redemptive arch from God’s future to the present, which includes all people,” Doi explains.10

Looking to Christ’s teaching, Doi was particularly struck by a New Testament account (Luke 20:27-40) in which Jesus explains that in the resurrection marriage will no longer exist. Based on this passage, Doi had the epiphany that all marriage is provisional and therefore based on fidelity between two people, regardless of their gender.

Doi not only invited his congregation to study and dialogue about same-sex unions, he counsels other ministers about how to be more inclusive. He also attends LGBTQ+ community gatherings to express clergy support for gay people.

Rev. John Oda, Program Manager for Asian American Language Ministry Plan for the United Methodist Church, had for years pastored the Lake Park United Methodist Church in Oakland, a historically Nikkei congregation. Oda’s support for LGBTQ+ inclusion in the Methodist church is grounded in family history. He traces his advocacy for the marginalized, including gay people, to the racism his parents and other family members endured, especially their incarceration during World War II. He connects historical discrimination against Nikkei to contemporary homophobia.

Another motivating factor was the experience of a close relative who came out in the 1980s but returned to the closet after attending a conservative church which condemned homosexuality as a sin. Oda was outraged that a pastor would use the power of his pulpit to preach such an unloving message. As Oda began increasing his advocacy for the LGBTQ+ community, he met more and more Asian Americans whose families rejected them after they came out. “That just broke my heart,” Oda recounted.11

Oda has taken leadership roles in regional and national bodies within and affiliated with the United Methodist Church to advocate for the ordination of openly gay clergy, for same-sex weddings to take place in Methodist churches, and for the full-inclusion of LGTBQ+ people in every level of the church.

Since the 1980s and the rise of fundamentalism, Christians have more often been associated with vocally condemning gay people than standing up for their rights. These Nikkei ministers provide alternate examples. That the Rev. Mineo Katagiri was a steady ally to gay people is particularly remarkable given the era in which he advocated for gay people. In the mid-1960s, societal attitudes towards homosexuality were much harsher than now, and most Christians, when they thought of gay people at all, judged them as sinners.

According to Katagiri’s daughter, Iao, “He wouldn’t have portrayed himself as a gay rights activist. He was a people activist.”12

Katagiri’s advocacy for acceptance of gay people and his support for other communities that were “disinherited in our culture” reflected his belief that barriers limiting individuals’ self-empowerment had to be dismantled for society to progress.

Katagiri believed that gay people and others on the margins deserved nothing less than to live lives of integrity and dignity.

Notes:

1. Katagiri, Mineo. Interviewed by Yuri Tsunehiro. October 10, 1993. Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i. P. 28.

2. Mineo Katagiri, “Prospectus. Metropolitan Mission.” Washington North Idaho Conference of the United Church of Christ. (unpublished manuscript, no date), typescript. P. 2

3. Gary Atkins, Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 96-99

4. Gary Atkins, Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 96-99

5. Seattle Daily Times (Seattle, Washington), May 28, 1969: 35. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/documentview?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A127D718D1E33F961%40EANX-NB-12D3365E5C697496%402440370-12D3352401098E32%4034-12D3352401098E32%40..

6. Mineo Katagiri, “Report to Urban Ministry Department, Board of Homeland Ministries.” (unpublished manuscript, October 1, 1966), typescript. P. 2

7. Gary Atkins, Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 99

8. Mineo Katagiri, “Speech Over Station KRAB.” (unpublished manuscript, April 13, 1965), typescript. PP. 3-4

9. Obituary of Reverend Lloyd Keigo Wake, Nichi Bei, February 15, 2018.

10. Doi, Kevin. Interview by Stan Yogi. Personal interview. Phone, May 29, 2019.

11. John Oda, E-mail, 2020

12. Katagiri, Iao. Interview by Stan Yogi. Personal interview. Santa Monica, February 21, 2019.

© 2020 Stan Yogi