More than half a century ago, Mineo Katagiri, a Nisei minister in Seattle, publicly championed the rights of gay people and facilitated the formation of the first gay-rights organization in that city.

The straight, married clergyman forged an unusual path to advocate for the acceptance of gay people in an era when homosexuality was not only the target of religious condemnation but also legal criminalization.

But his stance was consistent with his belief that society would not prosper unless it encouraged self-worth and empowerment for every individual, especially those most scorned and oppressed.

Calling to the Ministry

When asked what led to his calling as a Christian minister, United Church of Christ pastor Mineo Katagiri told this story: In 1939, Katagiri was an undergraduate at the University of Hawai’i, aiming to be a lawyer. In August of that year, he was a member of the University of Hawai’i YMCA’s delegation to the World Conference of Christian Youth, which took place in Amsterdam.

Fifteen months earlier, Nazi troops annexed Austria. Violence against Jews in Germany was increasing. The YMCA, nevertheless, held its conference in The Netherlands against a backdrop of intense international tensions.

At the conclusion of the conference, Katagiri and some of his YMCA friends traveled through Germany as tourists, just weeks before German troops invaded Poland, marking the start of World War II.

On a train from Mainz to Heidelberg, Katagiri became seriously ill. The managers of the hotel where Katagiri was staying summoned a doctor who told the young man, “You’re a very sick boy. You have a very bad strep throat, and it’s inflamed, and your fever is very high.”1 The physician instructed the hotel staff to fetch medication, and he said he would return the following day.

Katagiri believed he was dying. And he didn’t want to die in Nazi Germany. He made a deal with God: “Well, God,” Katagiri later explained, recounting his thoughts at the time. “I’ll make a bargain with you. You see to it that I get back, and I’ll serve the church.”2

The following morning, the doctor returned. He incredulously exclaimed, “It’s just a miracle!” Your fever is gone. Your throat is clear. You can get up and go.”3

Katagiri kept his end of the Divine bargain. Upon returning to Hawai’i, he focused on becoming a Christian minister.

Seeds of Social Justice Consciousness

Not much in Katagiri’s life prior to his participation in the World Conference of Christian Youth indicated he would become a clergyman. Although he was a leader of the University of Hawai’i’s YMCA, a Christian group, Katagiri was drawn to the organization not because of its spiritual values but because of its organized athletics. He was an avid baseball and basketball player.

His immigrant parents were not Christian: His mother and father, who worked as barbers in Haleiwa, on Oahu’s north shore, were Buddhist. His father supplemented the family’s income by selling liquor brewed in the back of the family’s barber shop and by preparing sashimi from fish he caught in a nearby river.

But as a child, Katagiri witnessed injustices that planted seeds for his social justice-focused ministry. Katagiri worked as a “water boy” in the sugar cane fields of Waialua, but his tenure was short. He told the field boss that the workers needed more breaks and shade under which to eat lunch. He was promptly fired.

A few years later, Katagiri worked in the fields owned and operated by the Hawaiian Pineapple Company. One of Katagiri’s fellow workers, an older man, repeatedly complained to his younger colleague how much money the owners were making through the workers’ sweat. Yet, the laborers earned only two dollars a day, working ten hours a day, under unsanitary and primitive conditions. Katagiri later recalled, “He kept telling me how he would love to get his hands on the employers and put them in their places. But he had no way, no means by which to air his grievances.” One night, the man snapped. Carrying a large knife, he hunted for the plantation boss. “The next day, he vanished from camp,” Katagiri recounted, not knowing the fate of his fellow worker.4

“My hatred of the plantation system has become an emotional one,” he wrote of that incident. “My life has therefore been one of quest for means and methods of breaking such a system.”5

Katagiri initially thought the best way he could combat oppressive structures was to become a lawyer. Teachers had told him he had the gift of gab. He could put it to use as an attorney. But after the World Conference of Christian Youth, he shifted his focus to the ministry. “I knew very little about the Christian faith then,” Katagiri wrote in a seminary paper, “but my experience at that great conference turned my thoughts toward the Christian Church. The Church, a fellowship of human beings with each other and with God revealed in Jesus Christ, received my attention since.”6

Attending Union Theological Seminary

At the urging of his friend Abraham Akaka (who also participated in the 1939 World Conference of Christian Youth and became a clergy and civic leader in Hawai’i), Katagiri entered Union Theological Seminary after graduating from University of Hawai’i.

The seminary was known for its social justice focus. In the classrooms of the imposing stone institution located in West Harlem, Katagiri met students (albeit mostly white men) from all over the country. Well-known theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, a professor of social ethics, was one of Katagiri’s counselors. Because of his YMCA friends, Katagiri became associated with the United Church of Christ (UCC), a progressive denomination.

After witnessing the slave-like conditions and viciousness of the Hawaiian plantation system, Katagiri resolved that violence never results in good. He became a pacifist. Soon after Katagiri entered seminary, the Japanese military attacked the Pearl Harbor naval base. Many of his childhood and college friends, as well as many of his relatives, volunteered for the legendary all-Japanese American 100th battalion.

In 1944, as Katagiri was preparing to graduate from Union Theological Seminary, he received a draft notice. He reported to his local draft board in Harlem and declared himself a conscientious objector.

As a seminarian, he could easily make the case that his religious convictions propelled his pacifism. Friends and relatives, though, criticized the budding minister’s decision. “He was going against the other men in his family and in his neighborhood,” his youngest child, Iao, explained about her father’s choice. Katagiri stood firm in his beliefs. “Once he set his mind to something, nothing swayed him,” said Iao.7

The Impact of Race

Beginning in the late 1850s, plantation owners in Hawai’i recruited successive waves of immigrant laborers – from China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines and Portugal – to toil in the sugar and pineapple fields. Katagiri recognized that plantation owners used divide-and-conquer tactics, like segregated housing and differential wages, to prevent their multi-racial labor force from organizing for better working conditions. In 1944, he wrote that plantation workers “at the moment are made to believe and do believe that the enemies of their own progress are other workers. Thus the Japanese believes that his enemy is the Portuguese who has consistently acted as a strikebreaker.” He also recognized, though, that the “time is fast approaching when organization across race lines will be inevitable.”8

Katagiri didn’t experience that kind of racial unity in his first assignment as a minister. The United Church of Christ sent the new seminary graduate to serve as an assistant pastor in Kentucky. When Katagiri met the church’s leaders, they were shocked that their new minister was Japanese American. The United States was still at war with Japan. Most likely few, if any, people in that Southern community had ever met someone of Japanese descent. They were instead fed government propaganda depicting Japanese as sinister, buck-toothed enemies.

Nevertheless, church members welcomed Katagiri. Within two weeks, however, church deacons heard rumblings that some of their neighbors objected to a Japanese American living among them. Congregation leaders feared for Katagiri’s safety. Not long after he arrived in Kentucky, church members smuggled him out of town and sent him to a church in Oak Brook, Illinois, 20 miles west of Chicago, which had agreed to shelter him. That midwestern church eventually hired him as Assistant Pastor. He served there nearly a year.

Move to Seattle

Katagiri returned to Hawai’i in January 1945 and married his childhood sweetheart, Nobu Sasai. They raised three daughters while Katagiri served successively as a pastor at UCC parishes in Honolulu, Wailuku (Maui), and Kapa’a (Kauai). He was a beloved minister whom parishioners remembered for his inspirationally-booming baritone voice. When preaching, his diction shifted from a pidgin-accented lilt to that of a Boston brahmin.

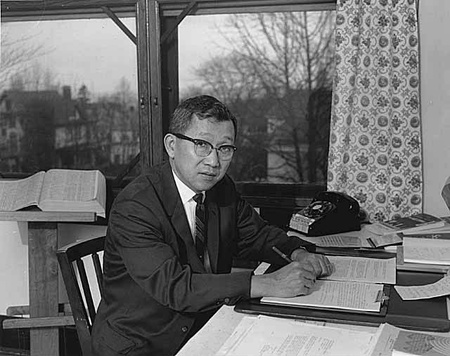

In 1959, following ticker tape parades celebrating Hawai’i admission to the union as the 50th state, the Katagiri family packed its belongings to move across the Pacific to Seattle, where Katagiri would begin a new job as Campus Pastor at the United Church of Christ’s congregation affiliated with the University of Washington.

At the time, it was the largest UCC church in the nation associated with a university. Katagiri was assigned to work with students. The spirited pastor was in his element. He played baseball and touch football with young men and bonded with them through conversations about sports. Students responded to Katagiri’s bouncy energy, wit, and kindness. He did not preach at them but instead listened to their concerns. Katagiri felt that individuals should decide for themselves what religious convictions, if any, to claim. He believed his job was to welcome all the students he met.

Because of Katagiri’s open attitudes during an era when many of their parents were no doubt more close-minded about topics like religion, young people trusted the charismatic minister. Katagiri built a supportive community, as students brought their friends to the campus ministry’s clubhouse-like building across the street from the church.

Although he bonded with undergraduates over secular interests like athletics, he never shied away from references to his faith. His success building relationships with students resulted, in part, from their perception of his honesty and integrity.

Notes:

1. Katagiri, Mineo. Interviewed by Yuri Tsunehiro. October 10, 1993. Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i. P. 13.

2. Katagiri, Mineo. Interviewed by Yuri Tsunehiro. October 10, 1993. Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i. P. 14.

3.Katagiri, Mineo. Interviewed by Yuri Tsunehiro. October 10, 1993. Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i. P. 14.

4.Mineo Katagiri, “Racial Equality in the Labor Movement” (unpublished manuscript April 19, 1944), typescript. P. I.

5. Mineo Katagiri, “Racial Equality in the Labor Movement” (unpublished manuscript April 19, 1944), typescript. P. II.

6. Mineo Katagiri, “Racial Equality in the Labor Movement” (unpublished manuscript April 19, 1944), typescript. P. II.

7. Katagiri, Iao. Interview by Stan Yogi. Personal interview. Santa Monica, February 21, 2019.

8. Mineo Katagiri, “Racial Equality in the Labor Movement” (unpublished manuscript April 19, 1944), typescript. P. 8.

© 2020 Stan Yogi