It was April 2004. I was attending an event at Columbia University in New York City. The organizers allotted us some extra time during the lunch break, and so I decided to go off and take a walk. I had worked at Columbia a decade earlier, and it was fun to explore the area around campus and see how the neighborhood had changed since then. It seemed that a number of the places I used to visit had vanished, but I was relieved to find that my favorite used bookshops on Amsterdam Avenue were still around, and I gladly went in one to check it out. (I love bookstores: I have often stated that my favorite activity is going to a bookstore and buying books –and my second-favorite activity is going to a bookstore and NOT buying books).

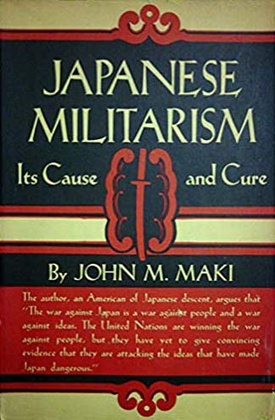

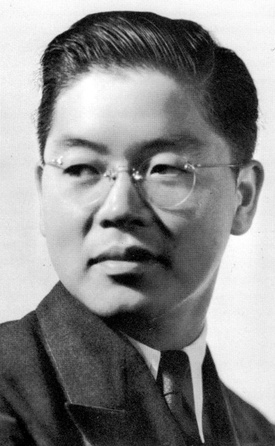

While browsing the shelves, I came across a book entitled Japanese Militarism: Its Cause and Cure. Upon checking the dust jacket, I saw that it had been published by the well-known firm Alfred A. Knopf during the Second World War: its back cover included a note on paper restrictions, and the text inside was laid out in small, crowded type to fit in extra content. On the rear flap was a photo of the book’s author, John M. Maki. A capsule biography underneath described Maki as an American of Japanese descent who had spent time studying in Japan, then taught at University of Washington. Since 1942, he had been doing war work for the government in Washington, DC.

I bought the book, and over the next few days I proceeded to read through it. As its title indicated, the work was a rather clinical analysis of Japanese society, designed to explained how Japan’s feudal and military caste rose to a position of dominance. Maki contended that militarism was so ingrained in Japanese culture that a genuine peace with Japan could not be established until the social myths which underlay Japan’s aggressive policies had been crushed through drastic action.

I was intrigued to see that Maki, writing even before the end of the Pacific War, had counseled against executing the Emperor of Japan and thereby transforming him into a martyr. Even if he agreed that the destruction of the imperial system was desirable, it could only be truly achieved through an internal revolution, which was highly unlikely in Japan. Otherwise, American authorities would be better advised to retain the emperor as a figurehead.

While I found the book interesting as a historical artifact, what I found more intriguing was the identity of the author. I vaguely recalled having gone through some official government archives some time before, and coming across an incomplete clipping of an article from the New York Post (a liberal newspaper in that long-bygone era) on Maki.

However, aside from that, his name had never been featured in discussions of Japanese Americans. How had he managed to work for the government instead of being confined in WRA camps, and what had become of him after the war?

Upon returning home to Montreal, I was inspired to find out what I could about Maki. I checked to see if he had written more books, and found the titles of several volumes. A book review of one of his later works stated that Maki was a professor at University of Massachusetts, Amherst. I decided to check the white pages for Amherst, and found a listing for one John Maki. Now, I had seen on the book jacket of Japanese Militarism that Maki was born in 1909, so I presumed he must be already dead, since he would be in his mid-90s if he were still alive. Still, I decided to try calling, in case there was a surviving spouse or child to give me information. Telephoning strangers out of the blue is always an ordeal for me, but after mustering the courage, I dialed the number listed.

A male voice answered, and when I asked whether Professor John Maki was there, to my surprise the voice replied, “This is John Maki.” I mentioned coming across his book, and he explained that, yes, he had written it during World War II while working for the Office of War Information. I expressed surprise that he had been able to do both things at the same time. I was even more surprised when he told me that after he retired in 1980, he had continued writing, and in fact was just then in the final stages of work on a memoir.

When I tried to ask some further questions, Professor Maki politely interrupted me. He explained that, with his advanced age, he was unable to hear clearly on the telephone. Could I possibly send him a list of questions by email? Next to Maki’s being alive and in good health, this request was the most stunning part of the conversation. I had always thought of email as a tool by young people, and had never heard of a nonagenarian using such technology!

I proceeded to make up a set of questions and quickly sent them off. Professor Maki wrote back within 24 hours. He addressed me as Greg, and prefaced his response by stating, “America's is a first-name culture. That explains the "Greg". And I'll be "Jack" in what I hope will be a continuing correspondence.” He told me that he would send me a copy of his memoir, which would answer my more general questions, and then went on to respond to some more specific questions.

Jack’s message to me did indeed lead to further exchanges, and his sending me a copy of his promised memoir. Jack’s story, as I learned it, was really fascinating: he was a Nisei (a word he preferred to “Japanese American”) who had been given up as a baby by his parents and adopted by a kindly white couple, the McGilvreys, who bestowed their family name on him. The young John McGilvrey had attended University of Washington as a major in English literature. During his time there, he had supported himself as a writer and editor for James Sakamoto’s fledgling Nisei newspaper Japanese American Courier, wherehe had also met and befriended Bill Hosokawa, a fellow staffer six years his junior. Hosokawa introduced him to a Nisei woman, Mary Yasumura, and served as best man at their wedding.

Jack entered graduate school at UW, but was dissuaded from pursuing a career as an English teacher or journalist by a professor who told him, “You’ll never get a job with that Japanese face.” Instead, he took the hint to transfer to “oriental studies” and take up a fellowship, sponsored by the Japanese government, to study in Japan. He left for Tokyo, taking his new wife Mary with him. (On the advice of Mr. Yasumura, his father-in-law, John McGilvrey “orientalized” his name to John M. Maki). Since he was raised in a white family and lacked a Japanese cultural background, he had to learn Japanese language and customs from the beginning. After returning from Japan, he had taught at University of Washington until the outbreak of the Pacific War.

During Spring 1942, following Executive Order 9066, John and Mary Maki were removed to Puyallup (Camp Harmony). However, Professor George Taylor, Maki’s boss at UW, rescued the couple from confinement by getting Jack a job doing war work in Washington as a Japan analyst, first for the Federal Communications Commission and later with the Office of War Information.

It was an enduring paradox that Jack, who had not grown up in an ethnic Japanese community and who lacked significant connections with them, was thereby considered “safe” for government work, and was selected above all others to advise on Japan. He did not even get much chance to use his (inadequate) Japanese language skills while in government service, but worked from documents translated by others.

It was while he was at OWI that Jack had the idea to write a book on Japan. Japanese Militarism came out just as the Pacific War drew to a close. It was the first book by a West Coast Nisei to appear with a mainstream American press. While it achieved only modest commercial success, it helped launch Maki into an advisory position with the U.S. Occupation forces in Japan following the end of the war. Upon his return from Japan, he studied for a Ph. D at Harvard University—where his professors allowed him to use Japanese Militarism, slightly tweaked, as his thesis. He ultimately spent his career as a professor of Japanese studies, first at University of Washington and later at University of Massachusetts. He also worked at both universities as an administrator, rising to the position of Dean at U-Mass.

Over the two years that followed my first exchange with Jack, we continued to correspond, both about his career and about other professional and personal matters. Jack was pleased and amused when I sent him copies of essays and poems he had published in the Nisei press during the 1930s, much of which he had forgotten. He kindly shared with me copies of his FBI file, which he had acquired. He also invited me to come see him in Amherst. Thanks to my friend and collaborator Elena Tajima Creef, who drove me over from Boston, in 2005 I was able to visit Jack at his lovely house, which was set in the middle of a stretch of woods. Although Jack had been a solid and even rotund man in his earlier life, he was a thin and somewhat frail-looking man when I met him, but he had a bubbly personality. We discussed American history and Jack told stories of some of the people (Nisei and others) he had worked with. He also showed me the decoration he had received from the emperor of Japan, the Order of the Rising Sun.

Once I got to know Jack better, I told him of my interest in writing a biographical study. As a little exercise, I sent him the draft of an article I wrote on him for an encyclopedia of Asian American literature. He returned it with his corrections and comments (just in time for his 97th birthday!). In late 2007 I made plans to return to Amherst to interview him again. Sadly, just before I was to visit, Jack fell while in his house and was unable to get up. He spent the night on the floor before he was discovered and rescued. In the process, he fell ill from pneumonia, and was taken to the hospital. So determined was Jack not to disappoint me that he commissioned his son John and his neighbor Rob Snyder (who, by a cheerful coincidence, was also the uncle of my dear friend Ben Carton) to solicit questions from me. I quickly drew up a few questions, which Rob brought to ask Jack in the hospital and then relayed back to me his responses. Jack never regained his health, and he died in the hospital shortly afterwards.

John Maki was one of the first West Coast Nisei to achieve mainstream success as a scholar and academic. By the time we met, he was 95 years old and reaching the tail end of his 70-year writing career. Fortunately, he was ready to continue making new friends and keeping up his end of the correspondence. Even if we only met face to face once, I felt that I got to know him. It remains a thrill for me to have had him in my life.

© 2020 Greg Robinson