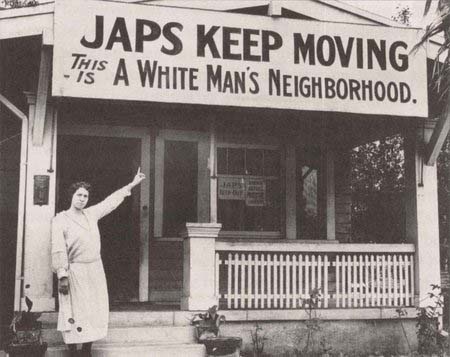

At the end of 1910, the number of Japanese immigrants in the United States had reached nearly 80,000; in Mexico and Peru there were more than 10,000 workers in each country, while in Brazil more than 5,000 were already working. As the number of Japanese immigrants grew on the continent, racist sectors of North American society fostered hatred and persecution against immigrants. To combat the arrival of Japanese workers, these sectors did not stop spreading false news and rumors pointing out the “danger” they represented for North American society by considering them as part of “degenerate races” that contaminated, as if they were viruses, the “purity.” ” race they wanted for the United States.

The anti-Japanese feelings that were expressed very violently in California spread to various countries in America. The reasons for understanding the aversion against immigration can be explained from two situations: the first is related to the objective of the government and a large part of North American society to build a homogeneous nation, with an exclusively Caucasian population. As Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson came to consider in a veiled way in the first decades of the 20th century, the purpose was to avoid mixing with this type of immigrants.

The measures to prevent the entry of immigrants who did not correspond to the characteristics of “racial purity” had already advanced very punctually since a series of exclusionary laws began to be enacted, the first of them against immigrants of Chinese origin in 1882. The ideas of “racial supremacy” proposed by these sectors also sought to be based on science, using, for example, Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. Furthermore, “racist culture” had been popularized through a large number of literary works such as those of the Nobel Prize winner for literature, the Englishman Rudyard Kipling. At the beginning of the century, therefore, it was not strange that anti-Japanese activities and organizations had great success in the white society of the state of California where the majority of Japanese immigrants had been concentrated.

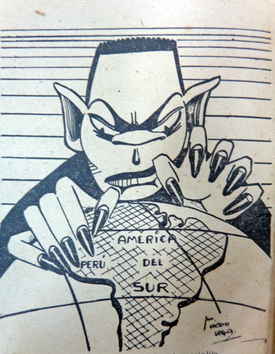

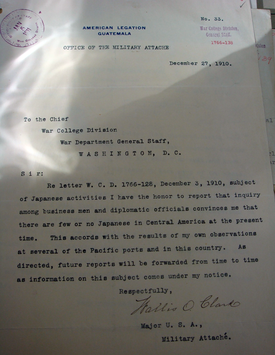

The other element that helped strengthen xenophobia against immigrants, especially Japanese, was due to the consolidation of Japan's empire as a great power and the gradual confrontation with the United States. Although the Japanese were widely recognized as honest, responsible and hard-working, the international situation led the North American government to instruct all its embassies in Latin American countries to monitor not only the activities of Japanese businessmen and diplomats but also the immigrants themselves.

In this context, anti-Japan rumors also played an important role in generating fear and repulsion against immigrants on the continent. The North American press echoed this atmosphere and spread a series of lies such as that the Japanese immigrants working in Mexico were actually part of the imperial Japanese army that was preparing a future invasion of the United States.

At the beginning of 1911, Massachusetts Senator Henry Lodge stated that the Imperial Japanese Navy would purchase Magdalena Bay in Baja California. The bay, important for its strategic geographical location, had been used by the North American Navy to carry out naval exercises with the consent of the Mexican government. On the other hand, the owner of the most important newspaper chain in California, Randolph Hearst, actively participated in that campaign by spreading rumors and publishing alarming and false news such as the arrival of 75 thousand Japanese to Magdalena Bay. The scandal reached such magnitude that it had to be categorically denied by the Mexican and Japanese authorities.

Senator Lodge, like magnate Hearst, was fully convinced of the so-called “yellow peril” that the entire continent supposedly faced by allowing the immigration of Japanese workers. Both became the most important promoters of laws against non-white immigrants and the most active disseminators of the racial superiority that was established in eugenicist theories such as those of the English scientist Francis Galton.

The anti-Japanese movement in the United States would achieve its goal in the years to come. In 1913, a law was passed in California so that Japanese farmers could not acquire land for their crops. But without a doubt, the definitive success of all these movements against immigrants came in 1924 when the president of the United States, Kalvin Coolidge, himself approved an executive law that limited the entry of immigrants who were not white. .

As World War II approached, harassment of Japanese immigrants and their descendants was unleashed with great fury. Lies continued to play an important role in attacking them violently. In May 1940, in the city of Lima, Peru, rumors spread claiming that Japanese immigrants were hiding weapons with the purpose of overthrowing the government. The rumor caused angry mobs to attack the immigrants' businesses and homes, causing their destruction. The material damage was considerable, but the most painful thing was the repatriation of 64 families who were left homeless and who preferred to return to Japan even though they had been living and working hard in Peru for decades.

When the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the North American naval base at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, stated without any support that the attack had been possible due to the work of the “fifth column” embedded in Hawaii, referring to the entire immigrant community. The FBI denied this information, stating very clearly that the Japanese communities had not participated in this attack nor had they provided information for this to happen.

However, these fake news created great fear in the United States and other countries that had large numbers of Japanese, such as Mexico, Peru and Brazil. Rumors and lies were the reason why Japanese communities were considered invading columns willing to blindly follow orders from Tokyo. American governments decreed the transfer of thousands of immigrants and their families to concentration camps or large cities to be closely monitored. In the United States, 120,000 Japanese and their descendants (two thirds of them were born in that country) were forced to leave their homes and concentrate in 10 camps created for this purpose.

Unfortunately, these racist demons, lies and rumors have been unleashed at this time when we are going through the most terrible pandemic we have ever experienced: the coronavirus. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that the world faces, in addition to the covid-19 pandemic, another one that has dominated as an “infodemic.” This latest pandemic refers to the large amount of false information that circulates massively on social networks and has generated a wave of racism, confusion and misinformation.

The first of these racist insinuations was to assign an ethnic or racial character to the coronavirus. It has been called the “Chinese virus” when in fact its scientific name is SARS-CoV-2, designated by the WHO to avoid these racial connotations. The other is to falsely claim that the coronavirus has been created in a laboratory to function as a “biological weapon.” The WHO, faced with such a situation, has created a special site on its website , in multiple languages, especially dedicated to combating such lies through truthful and scientific information about the origin of the coronavirus.

Lies, without a doubt, have historically been the basis for creating and promoting fear in the population with the purpose of discriminating and even massacring thousands of people based on their ethnic origin. In 1918, a major influenza pandemic broke out, known as the “Spanish flu,” causing the death of tens of millions of people. However, this influenza virus originated in the United States and was spread by American soldiers who moved to Europe during the First World War. Smallpox, by the way, was brought to the American continent by the Spanish soldiers who conquered Mexico and caused millions of deaths in the native populations. Viruses are part of the same human species and to the extent that the world is more integrated, they are transmitted more rapidly to various countries. Irrational fear and rumors about the coronavirus have caused nurses and medical personnel in Mexico and many other countries to be attacked and discriminated against when they are the ones who risk their lives to protect us.

The organization, solidarity and community work of Japanese immigrants in such difficult times made it possible to overcome the misfortunes they faced when the war broke out. The coronavirus pandemic that has spread globally can only be controlled with the determined and organized participation of communities that prevent its spread in the first place and through the cooperation of all countries so that the necessary vaccines are created in the future. and collective measures are taken to protect all of humanity against viruses. Lies, misinformation and racism are part of those pandemics that must also be fought.

© 2020 Sergio Hernández Galindo