YELLOW CHERRIES/YELLOW PERIL?!

I am intrigued by the story of post-internment Ontario Japanese Canadian (JC) history in the booklet you wrote. This is a story that isn’t often heard about.

MBG (Miiko Barbara Gravlin): I originally conceived of a child’s storybook based on my carefree experiences in Cedar Springs, Ontario. My childhood on the second farm was mainly happy, full of wide-eyed wonder and curiosity. I grew up reading Dick and Jane, their dog Spot, kids books. This didn’t reflect our family lifestyle. The concept for my child’s book was first called “What colour is Moby?” At the time, I submitted illustrated stories to Nikkei Voice newspaper changing its name to Life after Tashme. In 2019, the book was revamped from a fictional novel and became a mini childhood memoir Yellow Cherries - Life after Tashme.

Ontario farmers were in need of laborers so sponsored many JC families, like my family, to work their land and harvest crops. The first farmer my family worked for in Cedar Springs provided a humble house with bare necessities, an outhouse and a water pump in the backyard. As a child, I never knew about the removal of JCs from Vancouver, Tashme internment, Pearl Harbor, or WW2. I was aware of racism against my father and older siblings and other JC’s attending local schools.

What kind of racism?

MBG: Our first farm owner’s son used derogatory words towards my Dad. This partially influenced my Dad to eventually move our family accepting a better offer with another farmer in the area.

The elementary school adjacent to our first house had incidents of racism. Some JC students, including an older brother, were called racist epithets in situations. Some JC girls were given straps for little reason. I recall straps being handed out at the time to an autistic boy in my class. I was terrified of being singled out for a strap so became a ‘brown-noser’ and a high achiever - LOL.

Eventually, many JC families earned respect in the community by being honest hardworking citizens, doing well in school and being excellent in sports.

Your book Yellow Cherries focuses on post-war experiences. Why yellow cherries?

MBG: Yellow Cherries came together only months before it was published so became a hasty narrative despite the concept and stories incubating in my head for more than 10 years. My childhood years on the farm in Cedar Springs were carefree with occasional risky behavior being unsupervised. ‘Curiosity killed the cat’ and it’s a miracle at times youngsters like Mary and I survived playing in out of bounds areas like hay barns and gravel pits. Sitting amidst the red cherry trees sparked my artistic nature. The yellow cherry orchards were out of reach as the trees were too high to climb. Their fruit was especially sweet and sought after. To call my book ‘Yellow’ over ‘Red Cherries may have been my private facetious take on ‘Yellow Peril’ due to WW2 attitudes.

Are there others that you can share?

MBG: I have many other ‘tales’ that could make up a complete children’s book. There are vivid memories of our family life through the seasons on the farms. Here is a short episode from my book, Yellow Cherries. In Cedar Springs, the spring brought the smelt fishing season and the entire family was put to work. My Dad and brothers headed out to the shores of Lake Erie at dusk after the waters settled. The lake became alive with the tiny silvery smelts jumping up in the shallow waters. Bushel baskets of the fish were scooped up in an hour. The convenience store down the road stored them in their refrigerator for Dad. Over the days, my Mom, myself, and sisters washed, cleaned, and prepared the fish for meals and pickling in a teriyaki sauce for preserves. Some members in our family love fish like myself and others are repelled by the look and smell.

One winter the snowfall was so heavy, we couldn’t get out of our side door to go to school. We opened a window and tumbled out. Our older brothers made an igloo on the front yard the days afterwards. It was a wonder to step inside on a sunny day and I thought of what it was like to be an Eskimo.

My personal feelings about being settled to Ontario is that it made us a grossly displaced people. What are your own thoughts?

MM: Yes, I agree JCs were forcibly displaced by the Canadian government twice. The first happened in February, 1942 when it ordered the removal of all Japanese Canadians from the west coast to 100 miles inland and the second, when the JCs were not allowed to return to the west coast after WW2 ended.

MBG: Yes, I believe most JC’s interned in the camps feel the shroud of displacement. How it impacts one’s life is a personal choice. I’ve felt ‘displaced’ or alienated from an early age. Seeing my Dad work so hard in the wintry fields he would suffer pain and administer ‘moxa’ treatments to himself at bedtime. My Mother was so thin and ill around the Hastings Park confinement she could barely walk and was hospitalized briefly.

Most of us wish to remember only the positive and ‘gaman suru’ or bear with perseverance the negative. I believe one should embrace both, accept the past and not be hardened by life’s injustices. You become stronger when you go with the flow and survive like our parents.

Can you talk a bit about yourselves as artists? What kind of work occupies your time these days?

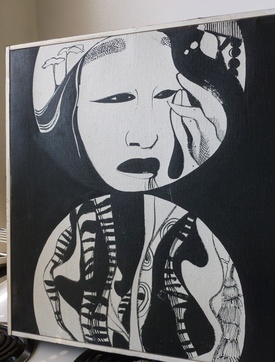

MBG: I’ve never had a home with a permanent space for painting so my creative works are sporadic. At 17 when my painting career started, I painted in the family kitchen and played music closing the door. It was a constant distraction as family members traipsed through. My paintings were stored in the basement. One day, I went downstairs and noticed a large canvas stored behind the furnace looking strange. Upon closer scrutiny, I discovered my Dad had removed the wood frame and cut off 3 inches all around the canvas. He nailed the leftover canvas to a piece of masonite and added the stretcher to replace the original frame. Dad was a practical man and obviously needed my wood frame for some project.

My working life has been divided between commercial projects through employment and painting when I could find the space. Once in my past, I signed up at a restaurant, “Joe DiMaggios’ Wet Paint Cafe” in order to have space to paint. That week I sold two paintings on the spot.

I am in the process of recharging myself after my book and the Tashme Sisters exhibit. I’ve been thinking of re-stretching a large canvas to paint a mural of the exodus of JCs into camps inspired by Picasso’s Guernica. I get a lot of ideas that don’t go beyond the inspiration. One artist’s motto is ‘to think first, feel, and produce art technically; I feel first, think and the technique comes with the action.

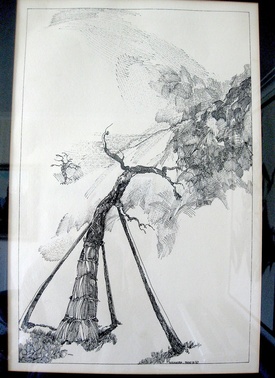

MM (Mary Morris): I consider myself an occasional artist since I paint only when the creative impulse comes and only for my own enjoyment. Although I always feel a serious need to progress technically and imaginatively with every painting. After I retired from teaching I started painting with watercolours, mostly figurative compositions in a particular setting. About 15 years ago I changed to painting large, representational landscapes with acrylics. Presently, I am still inspired by landscapes and nature based on photographs taken from my travels.

Is there particular importance for JCs who were forced to move to eastern Canada to tell their stories too? Ours is the forgotten one in the narrative, isn’t it?

MBG: It’s very important for JCs to tell their stories for future generations but it’s equally important to respect those who wish to live out their lives having earned their way in Canadian society and move on from the past injustices.

MM: It is definitely an important part of the JC narrative. Where did the JCs settle after the war? What were the emotional, mental and physical effects of the war experience on the JCs, their children and grandchildren?

What is your relationship with the province of BC today?

MBG: In 1974, I needed a change from Toronto so moved to Vancouver, B.C. I stayed with a brother and gave myself three months to find employment. I was hired by Thompson, Berwick, Pratt & Partners, a distinguished architectural firm in downtown Vancouver. The experience was rewarding working with professionals on a variety of projects—redevelopment of Granville Island, False Creek, Banff, etc. I encountered many instances of racism in Vancouver: lining up in Scottish meat shops or Safeway deli counters and not being served; being glared at playing as a guest at an exclusive tennis club.

I got to know an estranged Uncle who lived on his fishing boat. The internment separated him from his family for many decades. About the same time, my Mom’s oldest sister visited Canada for the first time. I was asked to meet my Aunt Tamura at customs as she arrived in Victoria from Japan in the mid-70s. She had a mountain of boxes and bags to declare - some leaky with Japanese pickles, food, and a large contraption for aiding rheumatism. I joked with the good-natured official who allowed her entry. My Aunt from Kumamoto would reunite with her brothers and sisters for the first time in Toronto—a joyous occasion.

MM: Yes, we have been to BC many times and love the natural beauty.

What was your experience as a JC growing up in Ontario and the Greater Toronto Area? As you grew up in small town Ontario as I did, what kind of experiences of racism did you have?

MM: Our parents worked for fruit farmers in Cedar Springs, a small, rural community in southwestern Ontario. When we moved to Toronto in 1956 there already existed a sizable JC community within the city.

As far as “experiences of racism,” although I always was aware of the existence of prejudice against Canadians of Japanese ancestry through movies and television shows, I cannot remember one instance of overt racism which happened to me personally. Perhaps I was one of the lucky ones; perhaps being the second youngest, I was not affected by it as much as my older brothers and sisters might have been.

During the fifties when we arrived in Toronto our west-end neighbourhood was populated by new Canadians mainly from Europe: Ukrainians, Dutch, Eastern Europeans, Italians, Scandinavians, etc. who immigrated from the ravages of WW2. The children I remember going to school with were just trying to fit into Canadian society, as were we JCs, so we were basically in the same boat.

MBG: Most of my experiences were positive growing up on a farm in a rural farm community except for a few unpleasant memories. I was the fifth child so not exposed to racism as directed to my father or older siblings.

There were a number of Dutch immigrants also working on local farms. I learned Dutch songs from a friend and walked to school with Dutch and English neighbours. Once we attended the local United church, we felt more accepted in the community taking part in concerts or services.

My Mom was a homemaker and worked briefly for Glen Gordon Manor in their bakery outside of Cedar Springs. My Dad worked farms, spraying fruit trees, harvested tobacco, beets, potatoes and fruit.

After the move to the GTA (Greater Toronto Area), Dad worked for a car dealership for many years. I did not want to move to big city Toronto and experienced racism for the first time. A youth knocked my shoulder on the way to school calling me ‘a dirty Jap’. I didn’t know why and what I had done to deserve the hateful assault.

I experienced other racist incidents in Toronto, quitting two management positions when confronted with derogatory quips. When promoted as art editor in a large publishing firm, I overheard myself called derogatory words by a woman in the cafeteria. I took it personally then but afterwards told myself, demeaning words reflect not who I am, but of the person who belittles.

All in all, how has life after Tashme been? How should that infamous place be remembered for posterity? Have you been there? Any particular memories? How did your parents deal with it after WW2?

MBG: Life after Tashme is an ongoing journey. Tashme will be remembered by the JCs who choose to tell their stories - and by artists who lived and shared their art I was fortunate to know: Shizuye Takashima (A Child In a Prison Camp) and artist Kazuo Nakamura from Tashme and others who followed.

I recall a story a relative shared before he passed away. He told of having to leave on 24 hours notice from the family home in Vancouver in 1942: “My older brothers took the suitcases and I had only a cardboard box to fill my personal belongings with”. For JCs, their dignity and rights were lost.

I have not returned to Tashme since it has become Sunshine Valley with its’ museum. In the mid 70s, there was a ski hill there. During the trip, my spouse and I went ‘Mutake’ or mushroom picking in the deep forests near Hope with directions offered by an elderly JC friend. It was exciting spotting a white mushroom peeping out from the dank earth under the pine trees. I’ve heard mushroom hunters resort to desperate means today to forage these delicacies.

MM: I have, like my parents, always tried to be optimistic in life in spite of the negative past and so, all in all, I have been very fortunate in my life. It took my parents, especially my father, many years to be able to even speak of what happened during the war.

In the summer of 1989, while travelling through B.C. on holidays, my family stopped near Hope and found the original site of Tashme which today is a park and camping resort called “Sunshine Valley”. It was a very moving experience knowing that my family lived for four, difficult years in that very location during the war. Sunshine Valley as Tashme an internment camp should never be forgotten.

TASHME SISTERS ART EXHIBITION AT THE TORONTO JCCC

How did that show go?

MBG: The Tashme Sisters show was well received by the public that view it. I would have liked to share the exhibit with a broader group outside of the JCCC (Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre) and did some marketing and promotional work myself. The selected pieces chosen by Bryce Kanbara, the curator installed the exhibit with excellent insight and expertise. He published a comprehensive brochure for the JCCC and it was sobering to read the truths he revealed describing our art and relationship. We owe Mr. Kanbara and the JCCC arts committee deep gratitude for the opportunity to be showcased and share our art.

MM: Tashme Sisters was a very positive experience for me. I particularly enjoyed talking to people about their experiences during the war and their connection to our family. Barb and I are only two years apart and both of us have had an intimate connection with art throughout our lives. The narrative Bryce Kanbara, the curator, presented was “Like many siblings, the Tashme Sisters are similar, but different” (JCCC Newsletter, October 2019). As many people who attended the show pointed out, the juxtaposition of my large, representational landscapes against Barb’s huge, expressionistic abstracts was startling and fascinating at the same time.

Bryce Kanbara was the driving and central force behind the show. He has a special curatorial talent and I very much appreciated the opportunity to display my paintings in the Japanese Canadian Cultural Center.

Were there intended lessons about the experience for younger generations of JC?

MBG: Younger generations should not be encumbered by their parents’ setbacks and pursue their dreams with passion.

MM: I totally agree. I remember my father saying that after the war he moved to Ontario with only $50, so basically the war left our family impoverished. When we were teenagers, our parents did not encourage Barb and I to follow art as a vocation because they did not think it would lead to a prosperous future. Perhaps they were right, but they also did not stand in the way of our dreams and ambitions.

What was the narrative of the story that you were telling?

MBG: The exhibit showed how two sisters born during the internment produce very different art forms growing up in the same environment. Since Mary and I were middle children, we had to find our own way and fend for ourselves when our parents and older siblings were busy working. As four Nishimura sisters, we have supported each other. One family member expressed after witnessing our show, our parents would have been proud.

MM: As children we drew constantly to entertain ourselves and so our creative abilities developed from a very early age.

What kind of feedback did you get from visitors to the show?

MM: As children Barb and I drew together constantly to entertain ourselves and so our creative abilities developed from a very early age. Our very different styles of art were a result of our divergent art backgrounds. I followed a more academic path taking Fine Arts at the University of Toronto and Barb an avant-garde route studying at the Ontario College of Art and The New School in Toronto.

One interesting story from the show: I met a JC couple who said they had in their possession a painting which I did when I was a student which was over 50 years ago. I did not remember the piece of art but apparently my mother who was a close friend of the husband’s mother, gave it to her as a gift. It was nice to know that the family kept it for all these years.

Any thoughts about the departure of Bryce from the JCCC?

MBG: I did not know Bryce very well before our exhibit but he is without a doubt, a very perceptive artist and highly accomplished curator. Over the decades, he has been a major player in showcasing JC artists both at the JCCC and at his ‘You Me’ Gallery in Hamilton which is a huge contribution to Canadian art.

Any hopes for that important gallery going forward?

MBG: I hope the JCCC gallery continues to showcase not only established JC artists but promotes new unknown artists - perhaps bring international artists into the mix. It would be amazing to see the gallery achieve greater prominence as an art centre in the GTA and beyond.

MM: My hope is that the gallery will continue on the innovative path for the JC art community created by Bryce Kanbara.

MOVING FORWARD....

As artists living in Ontario, going forward then what are your hopes and dreams for the Japanese Canadian community?

MM: All I can hope for is, as you say, for JCs to “go forward” but always remember the past.

MBG: I hope young, new artists of all types would step forward to translate their parents or grandparents history and stories in art, film or books and not be dissuaded by critics or naysayers. Taking the first step by writing the first lines or painting the first strokes is what matters.

Does being Japanese Canadian matter in 2020?

MM: Of course, all lives matter!

MBG: I feel many third and fourth generation JCs or grandchildren aren’t interested or aware of their internment history so 2020 is important to keep dialogue going. In our busy lives, take the time to speak to our children and grandchildren about what our parents and grandparents suffered losing their rights, property and dignity during WW2 in Canada.

What kind of understanding of your JC experiences do your grandkids have?

MBG: None at age two.

MM: My grandchildren are one-quarter Japanese and very young but I hope they will always remember that part of their roots and value their JC ancestry.

What does being JC mean to you now?

MBG: Many JCs have inter married perhaps due to the internment causing a subconscious need to be more invisible and accepted in Canadian society. The younger generation are busy with their careers and raising families. It’s a challenge to make time in busy lives to attend JC events and preserving the Japanese culture.

MM: I value the Japanese part of my background more than ever, now that it has been 75 years since the end of WW2 and the year of my birth. With each generation I see the assimilation of the Japanese Canadians into mainstream culture as a fact of life. So, I think more than ever we JCs have a responsibility to learn and remember our past for the future.

What might art have to offer the JC community in 2020?

MM: To me art has its place in any community. It is a vital form of communication as are other arts like music, literature, theatre, dance, movies, etc. to present ideas, culture and values. Art makes all of us more humane and civilized.

MBG: A reflection of its endurance. Art takes energy, vision and will power.

Any final thoughts?

MBG: We’re all given a life to create and leave it better for all who seek.

© 2020 Norm Ibuki