Sukeichi Kameoka was born on April 24, 1888, in Kojiro-mura, Kuga-gun, Yamaguchi-ken, Japan. He had three brothers. In the early 1900s, the 1905 Russo-Japanese War was looming overhead, and in Japan, conscription was mandatory for men of a certain age. Sukeichi left Japan to escape the draft (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19). He was also the second son in his family, so all of their possessions would be left to his older brother, and he would get nothing. So he left for America.

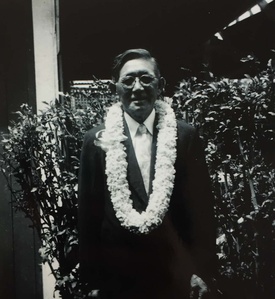

Sukeichi arrived in Hawaii in 1904, when he was just sixteen. At first, he was hired as a houseboy for a doctor. He would do odd jobs around the house, along with the housekeeping. The doctor paid for him to be sent to Iolani, one of the most prestigious private schools in all of Hawaii, to get an education. He excelled in both English and Japanese, and soon became a sign writer employed for a florist. He wrote signs for shops, funerals, etc. in Japanese. At this time, he took two picture brides, and under the second one, Yone Maeda, had three children, Elsie, the eldest daughter, Takayuki, their son, and Kazuko, their youngest daughter (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19). Afterwards, Sukeichi became the grounds keeper for the Pearl Harbor Yacht Club. He and his family lived in a cottage on that land, and Kazuko, two at the time, fondly remembers how she used to raid the storerooms there and drink the last few drops of beer at the bottom of the nearly empty beer bottles. He climbed the ranks, and eventually became the Chief Steward (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19).

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese. At the time, the Kameokas were living on the shoreline, and in the line of fire. As the bombing began, Elsie, the eldest, hurriedly helped her mom pack their things in the car and evacuated with Kazuko. Elsie’s brother, Takayuki, had died earlier in Japan during a visit, after catching typhoid fever on the boat ride over. He passed away two weeks before Kazuko’s birth. Sukeichi had owned three houses, renting out the other two that they weren’t using, and they traveled to one of them in Honolulu to escape the bombing. Sukeichi decided to stay. The Yacht Club was forced to close, and he became a laundry man at the nearby St. Francis Hospital, because that was the only job open to him at the time. (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19).

Sukeichi was arrested by the army on March 31, 1943. He was arrested for seven reasons, among them, the fact that he was said to be an illegal alien, one of his daughters held dual citizenship and the other was a Japanese citizen, he had participated in the Japanese census, and believed in the Shinto religion. Officials were also highly suspicious that he was an alien and was living in Pearl Harbor during the attack (Internee File for Sukeichi Kameoka, 1943, National Archives at College Park, 1945). He wrote a letter asking the government to authorize his release. He states “During my long residence in Hawaii I never did anything inimical to the laws and regulations of the United States, nor have I ever participated in any anti-American activities. . . . I love this country and have no intention of going back to Japan.” He listed some people to vouch for him, but the government ultimately turned him down (Internee File for Sukeichi Kameoka). He was quickly sent to Angel Island, San Francisco, with most of the other Japanese apprehended in Hawaii, and later was moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he stayed for the duration of the war.

During his stay at Santa Fe, he and the other Japanese refused to give up hope. They held their own festival there, building their own shrines and stages, and the men dressed up as women, since the camp was mostly men. They also painted stones, and he did some watercolor. Meanwhile, back in Hawaii, Elsie became a dressmaker, and Yone did laundry. Together, they scraped enough to get by, and sent a little extra to Sukeichi so he could buy cigarettes. There would be frequent blackouts and air raids, and they ended up digging a pit in the basement, under the house, in case Honolulu was bombed again (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19). Because of the high number of Japanese in Hawaii during the war, it was one of the places less impacted by the government removals. If they took everyone, there would be no one left to work and the economy would plummet. About 500 men were taken, community leaders and important people.

That was enough for a number of the young men who were left behind to volunteer for the United States army to show their patriotism to America. They became what was later known as the 100th Battalion and the 442nd regiment, an all Japanese regiment in the army, which would go on to become the most decorated regiment in American history. The Hawaiian Japanese and the Mainland Japanese didn’t get along with each other, and the Hawaiian Japanese jokingly called the Mainland Japanese “Kotonks”, the sound of an empty coconut, because that’s what their heads sounded like when hit. They were empty, so they sounded like an empty coconut (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19).

The women who were left behind stepped up and took over their husbands’ jobs. The war caused them to stop wearing kimono, and soon they ran all the managerial jobs. The daughters and younger men who stayed helped fill in the holes left by the older men when they were taken, and life soon returned to normal (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19).

Sukeichi was released on November 7, 1945 and sent back to Hawaii. There, he took up a position at the Pacific Yacht Club as a waiter, and soon became Head Waiter. He delved into his passion for watercolor, and did several watercolor paintings after the war, when he retired. He had always been a smoker and a drinker, and soon all that smoking had an impact. He was diagnosed with a cancerous tumor in his trachea, and died in 1959, at 69 years old (Interview with Kazuko Tengan, 11/23/19).

* This article was originally published on . For more information about the Japanese immigrant experience on the Angele Island during World War II, visit the history section of the AIISF website, which has a link to a database of over 600 people, and to read individual stories about those detained on Angel Island during World War II, read these stories from our Immigrant Voices website. Original funding for this project was supplied by the Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) program of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

© 2020 Marissa Shoji