“All I saw was cots and there were bales of hay or something, straw, that we were supposed to fill the mattress like, for our mattress. That I remember. We just took it, couldn’t be helped, you know. No point in complaining. ”

— Shizuko Yamauchi

In the spring of 2019, I was asked to conduct an oral history interview by the daughter of someone who had been in camp at Poston. It was a normal enough request, with one extraordinary fact: The woman I was to interview was 101 years old. At the time of Pearl Harbor Shizuko Yamauchi, then Inao, was 24 years old living in the coastal town of San Luis Obispo with her mother who sold tofu with her sisters. After being in Poston for just over a year, Shizuko left camp early in October of 1943 and headed for the Midwest with aspirations to become a stenographer. She eventually landed a job in Cleveland, married a veteran of the 442nd and became a mother to one daughter, Nancy Teruko (who joined us for the interview). Shizuko was a fixture in the Cleveland Buddhist church until the family moved back to the Newark area of California.

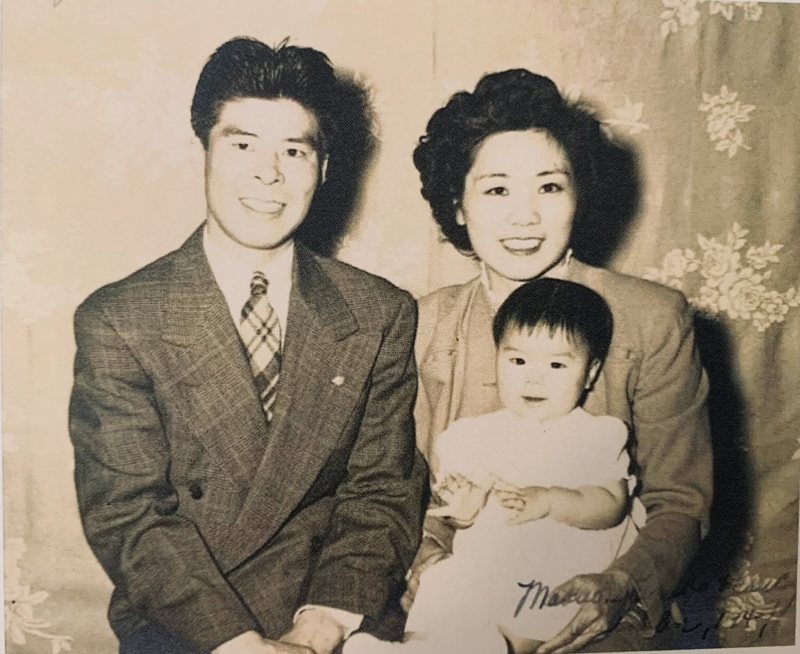

At the time of this interview, Shizuko was in a Japanese assisted living facility in Union City, adjacent to the Buddhist church. But I regret that she was not able to read this interview. She passed at the remarkable age of 102 on November 12, 2019. To live a life like hers with few regrets and a sense of humor, we can only aspire. Though her memories of the camp days and after were sparse, what she did share was sprinkled with plenty of candor and dry wit. After I remarked how beautiful she was in an old black and white photo of herself she chuckled and said plainly, “Well, everybody’s young once.”

* * * * *

What were your parents doing before the war?

Shizuko Yamauchi (SY): What were my parents doing? Farming, I guess.

Nancy Dodd (ND): Her father died when she was seven in an automobile accident. So her mother remarried. She’s one of four sisters.

And were you the youngest out of all the sisters?

SY: I was the third [eldest].

And your parents, were they Issei?

SY: My parents were Issei [from] Kumamoto.

Where were you living before the war?

SY: San Luis Obispo.

I haven’t heard of many Japanese Americans who lived in San Luis Obispo. I haven’t met a lot of families who were from there.

ND: Was it a small community?

SY: It wasn’t a really small community. We had a Japanese school.

And did you go to that school?

SY: I think I did [laughs]. It’s too long ago.

Do you remember the day Pearl Harbor happened? And do you remember hearing about it?

SY: Oh yes, oh yes, uh huh. I was for Japan and against Japan, you know. But I remember Pearl Harbor.

Do you remember how your parents reacted to it? Your mother and your stepfather.

SY: I think most of us felt like, shikata ga nai, it can’t be helped. Or, what can we do about it, you know?

Do you remember if there was any kind of backlash after that happened? Were people still kind to your family?

SY: I knew I was wondering how the hakujin would feel towards us. But there was no animosity. I didn’t feel afraid.

And what were you doing as a young woman at this time? Were you going to school or helping your family?

SY: I was already 25 years old so I wasn’t going to school.

You weren’t married by then, were you?

SY: No.

ND: Grandma had a boarding house and sold tofu, remember? My grandma would make tofu and she would go around selling the tofu.

So she had this business at the boarding house.

SY: I drove all over to the different houses and sold the tofu.

Do you remember what it was like when you were told to pack up and leave after Pearl Harbor after the Executive Order?

SY: Well I know, I never celebrated Christmas ‘cause I’m Buddhist. Well, my mother and I didn’t know where they were going to send us. So we didn’t know whether we should take clothing for cold weather or warm weather. That I remember, so. But it was shikata ga nai, you know? We just had to do what they told us to do, that’s all.

Do you remember anything important you had to leave behind?

SY: Well, I know we were renting the place, so we didn’t have to worry about that. But I don’t remember anything special.

ND: Mom, tell her, you spent your 25th birthday on the train going to Poston. I think she just went direct to Poston.

SY: Yeah, that I remember, that’s right. Well everything was shikata ga nai, you just had to take what happens, that’s all.

What else do you remember about the train ride going to Poston?

SY: Well, I just remember going through looked like desert part but then that’s about all. Just sort of wondering, well, just—wherever they take us.

When you got to Poston, what were some of your first impressions of the camp?

SY: Well, all I saw was cots and there were bales of hay or something, straw, that we were supposed to fill the mattress like, for our mattress. That I remember. We just took it, couldn’t be helped, you know. No point in complaining [laughs].

So do you remember the block you were in with your family?

SY: Block Three. Well I know that we had our bathrooms, to take a shower it was communal, you know. So those who were shy waited until 1 or 2 o’clock in the morning to go. I was old enough, thought what the heck. When you get older, you have, oh heck, it honestly doesn’t bother. We’re all alike.

Did you make friends in camp?

SY: Oh yes, oh yes. That was fine, you know, making friends in camp. Now I don’t know whether those friends are friends from camp or after I got here [in California]. It’s all mixed up.

Did you work in camp?

SY: Seems to me, I know for awhile I had to see that the mothers got their milk for their little kids. I don’t remember much—oh my. It’s too long ago.

What happened with going to Cleveland? How did you end up going?

SY: I went there because my friend was in Columbus. So I thought I’d go to Columbus but by the time I left, she had left Columbus so I just saw that well, Cleveland looks close by I’ll go to Cleveland.”

Out of all of your sisters, were you the only one to leave Poston?

By then my youngest sister was with her husband. And I was the next. Toshi, one sister was in Hawai’i. And the oldest was with her husband — he was a Kibei/Issei. So we were just separated.

So it was basically just your mom and your stepfather in camp.

SY: By then, I guess. Oh yeah, he was there. I know he had something to do—I knew he had quite a lot of education in Japan but we weren’t close. So he had something to do with regarding schooling I suppose. My mother was with her friends. She took advantage of it, she had her close friends and she enjoyed herself. She was able to do things with them so, ah things sort of floated, it didn’t matter what was going on.

When you actually left for Cleveland, what did you end up doing?

SY: Well, I got a job sewing at Joy Lingerie.

Did you already know how to sew?

SY: Oh yeah, oh yeah. I had gone to sewing school before camp. Japanese sewing school, yeah. That’s where my Japanese improved. It wasn’t like what I learned at home, it’s a little more refined [laughs]. I kept my mouth shut for a good two weeks, just listening.

Can you still speak it?

SY: In Japanese? In a way, yes. I watch my words when I’m talking with somebody that’s from Japan. But then, ah, they know I’m Nisei. They accept me as I am.

So you went to another college in Cleveland?

ND: I think business school.

SY: I—what should I say. It was a period where I didn’t use my shorthand typing so that’s why I had to catch up on my typing so that’s why I had to go there. Well I wanted to be a stenographer. So I was for about 20 years. Had the same boss, yeah.

That doesn’t happen anymore. that’s very rare.

SY: It was a real nice boss. He used to dictate letters to me and then take off before I typed them out. So I would sign it—initial his name. It worked. He trusted me.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on January 23, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida