“Finally, the day we received news of President Reagan signing the apology letter they had a function at the Issei Memorial building. And Papa was the only Issei there. I was so proud of him.”

— Shin Mune

Shin Mune is one of those rare living treasures in San Jose who come from the heritage of farming the very land upon which sprawling suburbias now sit. In fact, the 20-acre Mune farm that the family owned after the war was just a five minute walk away from the middle school that I attended, Morrill Middle on the border of Milpitas. Shin’s father and brothers had a knack for farming, and they excelled especially in growing tomatoes, as working the land seemed to be ingrained in their heritage. “Back then, all the Japanese immigrants were either farm workers or farm owners. My father must have worked for somebody during the time he was trying to get started as a farmer, but he wanted to be his own boss.” Shin speaks with a fondness and admiration of his first generation father to this day, recalling how he took him to the redress ceremony in San Jose’s Japantown after the Civil Liberties Act was signed, and remarkably, he was only Issei in attendance.

Though Shin knew that most fathers during that time wanted their sons to be white-collar professionals as opposed to farm laborers, Shin followed his family into the business. “I went one year to Berkeley, but I just didn't like being a civil engineer. I wanted to then sort of be a farmer, but farming was a hard life.” But he also made seeing the world a priority, and differed from his siblings in his desire to experience different lives and cultures. After our interview, Shin shared how the business of farming often took him to Mexico, allowing him to learn conversational Spanish. Shin and the Mune name remain closely tied to the Japanese American Museum of San Jose, as Mune Farms was the sponsor for several rotating exhibits, in honor of Shin’s brother, Kin, who passed in 2019. “We sponsored this [as a way] to honor my brother because without him, you know, everybody left the farm.”

* * * * *

My name is Shin Mune. I was born on April 27, 1937 in Santa Barbara, California. I was the oldest. I had a sister who was next to me and then Kin, a true farmer. And then Gene. So there were four of us. All born within a five and a half year period. So my mother had quite a hard life in camp.

Where were your parents from in Japan and what were their names?

My father's first name was Tokutaro, and my mother was Sasako. Nakanishi was the maiden name. They were from Wakayama. My mother came at eight years old with their mother and older sister. Her father had come here first with the oldest son. But my mother and her mother were taking care of my mother's grandmother. So that's why they couldn't come. I believe that story — I sort of got it second hand, but I've gone to the gravesite where her grandmother was buried. That’s in Wakayama. I've gone pretty often to Wakayama. Mostly it was my father's relatives that I stayed with, who have come to visit us here. So I was always welcome at their place.

Your mother was a young Issei when she came. Was she fluent in English?

Well, she learned English. She started third grade and she made a comment that was the hardest class that she's ever entered because she had to learn English almost quickly. All they did was speak Japanese at home. And then she had never learned to read or write Japanese because I don't know if she went to school.

How did your parents meet?

I don't think they knew each other in Wakayama while they were growing up. My father came at 14 years old. My grandfather had come earlier, but my father wanted to stay back and finish junior high school or go through another five years of schooling. He became very proficient in letter writing. He loved to write letters all in Japanese. I don’t think there was another letter writer like him. He would buy the Nichi Bei Times, subscribed to it. And he was a well-learned man reading the Nichi Bei Times daily back then. And then there was always an English section. So I've always enjoyed reading newspapers.

And my mother, because she was educated completely here in America, she subscribed to the San Jose afternoon newspaper. They had a morning and afternoon. So was either San Jose Mercury in the morning, or San Jose News in the afternoon. So we got the newspaper every day and we all as children became avid newspaper readers. And I can't think of another Issei lady who subscribed to the newspapers. Mama couldn't read Japanese, so Papa would get the Nichi Bei Times.

What did they do for work before the war?

Well, my mother settled in Menlo Park and they started a nursery. So in that area — Redwood City, East Palo Alto, Palo Alto, Menlo Park — there were I would say 30, 40 Japanese flower growers and they would grow carnations or mostly chrysanthemums in what were called these cheesecloth" houses. They weren't glass, but they weren't full plastic either. They were cheesecloth. It was thick enough to keep the warmth of the night after the sun went down. But also they could open it and let the flowers grow in the full flare of the sunlight.

So they were nursery owners.

My mother's side. And my father came here. And because back then, all the Japanese immigrants were either farm workers or farm owners. My father must have worked for somebody during the time he was trying to get started as a farmer, but he wanted to be his own boss.

Were your father’s parents farmers when they came?

My grandfather was already farming. My father stayed back. But my grandfather was a gambler and so Papa right away, he had to be his own boss. He just couldn't work under his father because my grandfather was just — lazy. My father worked hard. So my grandfather just the following year went to where my father was farming and lived with my father.

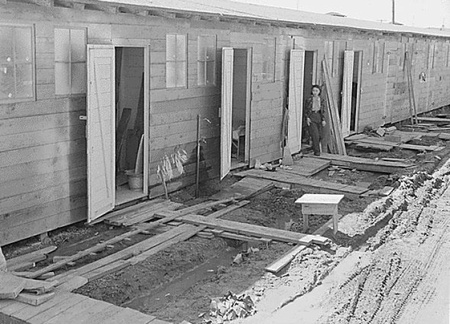

Then when we went to camp to Topaz, my grandfather, I remember he used to clean the grease traps and all the mess halls. And he would have this thing about six feet long with wire mesh to clean where the grease would go. And I still remember he would lean it against the barracks after he was done at night. Whenever you went in, I came outside. You did smell that grease trap. That was my grandpa. That was his job.

What happened to your grandmother?

I don't remember her. She passed away before WWII.

So your grandfather was alone?

Yes. And on my mother's side, I remember my grandmother and grandfather. But they went with my mother's older brother. They were with him. They were the flower growers. And they bought a property in East Palo Alto and built greenhouses. They had a full greenhouse to raise carnations. You need that in order to protect it from the cold. And then during the day, greenhouses, the glasses were sort of painted white to keep the sun glare from shining too brightly on the carnations. Because it couldn’t be too hot, it would almost burn the carnations.

It seems like they’re delicate.

To get the good size, you'd need to have the right temperature.

So since you were raised in Southern California, could you describe a typical day for you growing up before the war?

We were all four of us children born in Santa Barbara. The land that my father was mostly able to lease was always the hillside land. No well water, so what they did was plant peas. Peas was something you can plant the seed in the ground and it would stay in the ground for two, three weeks if there weren't any rain. And then the rains would come and germinate. But most seeds, if you planted, you could if you have a backyard. So that's what they planted. Although there were tomatoes, too.

But I remember Papa talking about the hillside land. The only land they could lease because most people you would hear of “marginal land.” And that's the term they used for Japanese who weren't able to lease. But they still could do it, which is that they could make farmland out of nothing. That was the ingenuity and the hard work of Japanese. It's amazing how they were able to, just through experience of coming here and working maybe for another farmer.

What do you remember about when Pearl Harbor happened?

I don't remember much after Pearl Harbor. Next door to our ranch was an oil storage facility and a Japanese submarine, a two man sub with a ship was moored off the coast. It came near the shore and lobbed shells into this oil storage facility. So what happened was the Japanese submarine two man sub, they just lobbed play shells. They didn't explode or anything, but they wanted to scare the American people on the coastline of California. It's hard to envision reading articles about cars that were screaming out of Los Angeles to leave because there were threats or rumors of airplanes coming to bomb Los Angeles.

And this happened? This submarine lobbing these shells. That actually happened, though?

It happened.

I've never heard of this.

Well, the American government never told people about it. They didn't want to scare — these armaments didn't explode. Well, I don't know. Some maybe exploded, but I call them “play shells” because they wanted to scare the American people. A two man sub isn't going to do much. But in order to get from where the ship was moored off the coast, maybe five, ten miles out, they had to traverse underwater because a rowboat would be spotted right away. And during that time, there were spotters along the coast. I met somebody whose father was a spotter.

And so almost immediately we had to move away inland. My father had two older sisters who lived in Centerville, which is now Fremont and they owned property, otherwise we would’ve had no place to go. And right around the first week in May, we went to Tanforan in 1942. So that would have been making me five years old. My younger sister, Satoko, about three and a half. My next youngest brother was about two and a half. And my youngest brother was only six months old when we entered. So my poor mother must've had it so terribly hard.

*This article was originally published in the Tessaku on April 15, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida