Although the saga of the Issei generation has been written by a number of historians, our understanding the views of Issei writers and thinkers on Japan is still incomplete. While the work of Eiichiro Azuma delves into the connections of the Issei to Japanese expansionism and the rise of militaristic nationalism, few have examined their counterparts who spoke out publicly against Japan’s move toward fascism, and who defended democracy. One such voice was that of Bunji Omura.

Bunji Omura was born in 1896 in Takakura, Fukuoka, Japan. Although his parents were farmers, his family belonged to a long line of samurai dating back to the 14th century. After moving to Tokyo to study law, and then railroad engineering, Omura left Japan and migrated to the United States in 1919, at age 23. Initially he entered as a seaman, but then jumped ship and remained in the United States as a farm laborer in California, where he attended night school to learn English.

In 1928, he returned to Japan for a few months, then re-entered the United States on a student visa. Omura enrolled at the College of the Pacific (now known as University of the Pacific) in Stockton, California, where he completed his bachelor’s in political science in 1929. During his senior year. he was president of the Japanese club. After graduation, he left California for New York, with the idea of pursuing an MA in public law at Columbia University. His MA thesis, produced the following year, was on “Local Government in Japan.”

While at Columbia, Omura became fascinated with the early Meiji period. His desire to understand the Meiji period led him to undertake a Ph.D in political science. Although he completed coursework for his doctorate, in the end he did not obtain his degree (according to family lore, he was not able to arrange publication of his thesis, which was required for graduation). Instead, he remained in New York as a freelance writer and instructor. During this period, Omura worked with International House, located at Columbia University. Through his activities there, Omura met a white woman, Martha Pilger, who was a specialist in German with degrees from Ripon College and University of Wisconsin. The two were wed in 1934, and remained together until Martha’s death 45 years later. The couple had two children, June and George. George Omura would later become a distinguished physician, while June Omura Goldberg was a journalist and editor.

During the 1930s, Omura watched anxiously as Japanese society slowly turned towards fascism. Following the Japanese incursion and occupation of Manchuria in 1931, Omura rose to prominence as an expert on Japanese foreign policy.

In October 1931, he debated Chinese community leader Chih Meng at Columbia University over the justice of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Omura denied that Tokyo intended to annex Manchuria, and insisted that Japan had entered Manchuria out of “absolute economic and strategic necessity,” given its growing population and lack of natural resources.

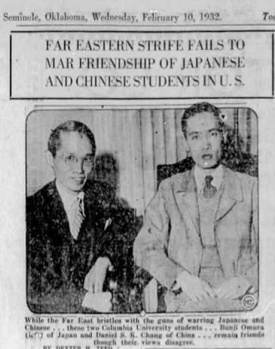

Similarly, in 1932, after Japan had established the puppet state of Manchukuo, Omura and Chinese scholar Daniel Chang presented a discussion at Columbia University, with Omura arguing that Tokyo’s intervention was driven by its justified attempt to protect its nationals from rising anti-Japanese sentiment. Nonetheless, Omura agreed that a third party intervention was needed to evaluate the situation fully.

Despite this hedged support for Japan’s occupation of Manchuria, Omura soon grew concerned over the assassinations of Japanese political leaders by the militaristic right, and he gradually became more openly critical of Japan. In an article, “Dagger and Pistol in the Hand of the Japanese Superpatriot,” published in Asia magazine in 1932, he warned that the recent wave of assassinations was the sign of a larger national crisis, one that revealed the dangerous state of unconscious feeling among the larger population.

In early 1934, Omura told an audience of students at Long Island University that the fascist movement was rapidly developing into a potent force in Japan. Soon after, he penned the article “Fascism Lures Japan,” for the journal Current History. It described the rise of Fascism in Japan as the exploitation of working class woes by military elites, and warned that ultranationalistic and non-parliamentary political forces were spreading rapidly throughout the nation.

Over the following years, in a series of articles, Omura critically examined different aspects of Japanese policy. For example, in the 1935 Asia article “What Profit Manchuria?”, Omura questioned whether the Japanese occupation was worthwhile.

Following the military’s failed February 26 coup in 1936, Omura produced a syndicated article for the United Press on the coup and the fascist message it sent, with the army ensuring that communist and leftist groups were “effectively wiped out so that fascism would be the only hope” for Japan.

In his 1940 Asia article “No Party Rule For Japan,” Omura denounced the Japanese army and its allies as composed of extremists blocking democratic rule. “These extremists have no intention of returning to the two-party system which Japan followed for a brief period in the Nineteen-Twenties. On the contrary, they intend to introduce in Japan the pattern of a totalitarian political set-up, similar to the Fascist, Nazi and Communist parties.” Meanwhile, Omura assisted author Edwin A. Falk with research for Falk’s 1936 book Togo and the Rise of Sea Power in Japan, which warned of the danger of Japanese naval power in the Pacific.

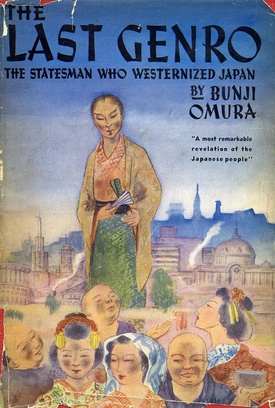

The rising tide of Japanese militarism also led Omura to transform his abandoned dissertation into a novel, The Last Genro. The Last Genro is a fictionalized version of the life of Prince Saionji Kinmochi, a leading Japanese liberal statesman who was twice prime minister of Japan and who helped select a dozen others. Presenting the prince’s life in gritty detail, Omura’s study narrates Kinmochi’s career from his youth in Paris to his rise in Meiji-era politics. Yet The Last Genro was more than just a biographical novel; rather, Omura used Kinmochi’s life as a basis for a broader discussion of Japan’s diverse political forces. Kimmochi himself embodied the antithesis of fascism; as a young man, he studied at the University of Paris, and he embraced a cosmopolitan world view over the decades that followed. He remained a pro-Western liberal, and opposed military supremacy. For Omura, such an alternative narrative was needed not only in Japan, but in the United States, where anti-Japanese publicists used Japanese militarism as a means of scapegoating the Japanese community in the U.S.

Omura’s novel was published in mid-1938, under the imprint of the distinguished Philadelphia publisher Lippincott. A British edition was put out at the same time by the publisher Harrap. Harrap was pointed in its advertising about the book’s theme: “Written by Bunji Omura, Japanese democrat, this book gets behind the bristling front of Japanese militarism.” The work was widely publicized and reviewed in the United States, though not always positively. Writing in the San Francisco Examiner, Isaac Don Levine called it a “charming and quaint work” and lauded the author as a “sincere democrat by conviction.” However, New York Times reviewer Katherine Woods slammed the book: “Developed in a strikingly colloquial style which lacks verisimilitude in just so far as it falls short of natural dignity and run through with several threads of romance, The Last Genro is not wholly satisfactory either as biography or as a novel.”

Not all of Omura’s works on Japan during the late 1930s were equally weighty. On a lighter note, during this period Omura produced a pair of articles, “Japan’s Happiest Village” and “Japan Speeds Up” for the tourist magazine Travel and in Esquire. He also published book reviews in The Nation and The New Republic. In a 1939 article, Omura was cited as stating that he was in the process of working on a second book, a study of the Japanese statesman Prince Ito. Omura was listed in the 1940 census as working as a writer and translator for a project of the New Deal agency Works Progress Administration. During 1940-41, he penned a brief history of the Japanese American press and other articles for the pro-Tokyo New York newspaper Japanese American Review.

Omura’s life, like that of other Issei, was strongly touched by the coming of the Pacific War. In a June 1941 article in the Seattle Taihoku Nippo, Omura called upon Japanese residents to support the United States in the event of war, expressing optimism that law-abiding Japanese would not be subjected to persecution. In the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, however, he became an enemy alien, with restricted movements.

During the war years, Omura enlisted in the war effort. He first offered his services as a Japanese teacher at the Naval Government School at Columbia University. Omura likewise produced for the Navy a dictionary of Japanese legal terms. He later offered his skills to the U.S. Army as a Japanese translator, working at the Military Government Translation Center in New York. Omura translated the first reports of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Outside of government work, Omura also worked for Fortune magazine, preparing articles for its special issue on Japan.

In 1945, the federal government instituted deportation proceedings against Omura as an illegal alien, and called him in for questioning. However, because of his outstanding wartime record and the potential damage to his family that would result from his expulsion, his deportation was suspended and he was permitted to stay in the United States. During this same period, he transferred to teach Japanese at the University of Michigan’s School of Military Government, then from 1946 to 1947 headed the Japanese translation section at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. His status nonetheless remained precarious until he was admitted to US citizenship in 1953, following the McCarran-Walter Immigration Act.

During the postwar era, Omura briefly worked for Voice of America, and ran a translation service. He continued to speak publicly as an expert on Japan. In a 1954 letter to the New York Times, Omura argued that anti-Americanism and militarism remained present, though dormant, in Japan despite the Occupation. Citing the lack of a formal police force and the instability of the Japanese economy, Omura argued that Americans should be wary of extremism in Japan and the potential rise of militarism.

In 1969 he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 6th rank, for promoting Japanese culture in the U.S. – a sign of Japan’s changing views on Omura’s vocal antifascism. In 1970 he debated union organizer Karl Yoneda in the pages of the New York Nichibei over alleged gaps in Bill Hosokawa’s book Nisei, The Quiet Americans.

By the time Bunji Omura died in September 1988, his earlier work had been all but forgotten. Still, Omura’s writings are important both for understanding the diverse views of the Japanese community towards militaristic Japan and the presence of Issei immigrants in American intellectual life. Likewise, Omura’s productive writing career for mainstream publications like The Nation and Fortune underscores the continuing importance of Issei who could offer expertise on Japan. While most anti-Japanese propagandists portrayed Japan as inherently servile to fascism, Omura stood out as a voice of reasoned analysis. Although Omura’s career in journalism was relatively brief, and The Last Genro remains his only published book, he nonetheless deserves further attention as an influential public intellectual and supporter of Japanese democracy in the years before the Second World War.

© 2020 Greg Robinson; Jonathan Van Hamelen