Despite racial prejudice and government pressure to move to the US, Irwin's children and grandchildren remained in Japan during the war as Japanese citizens. As adults, the grandchildren eventually moved to the US.

* * * * *

The war years

Robert Walker Irwin died of a stroke (noted as "apoplexy" on his death certificate) on January 5, 1925 while at home in Kojimachi, Tokyo. He was 81. His wife Iki died on August 17, 1940 at age 87. It was a blessing for Irwin and Iki to miss World War II. The heartbreak and hardships of the war were instead passed on to their children and grandchildren, who all opted to remain in Japan during the war.

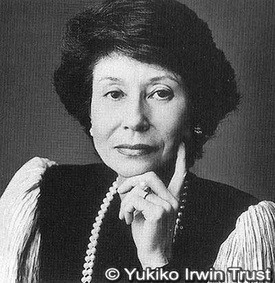

With both parents gone while they were still young, granddaughter Yukiko Irwin and her brother Takeo were raised by their Aunt Bella. In her memoir, Franklin no Kajitsu (Fruits of Franklin) published in 1988, Yukiko recalled many anecdotes about the Irwin family's life in Japan and the war years. It is a major reference source for this article and was used with permission from the Yukiko Irwin Trust.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941 (December 8 in Japan), the Irwins heard about it on the radio at home in Tokyo. Japan and America were now at war. Aunt Bella, Uncle Bob (Robert Jr.), and Aunt Agnes were distraught and left the room. "This is so terrible. Our lives will get harder," said one family member. Yukiko was a student at Tokyo Women's Christian College (Tokyo Joshi Daigaku) and writes that she dragged her feet to school that day. Her body felt as cold as ice.

Her aunts and uncles were ordered by the Japanese government to return to the United States. Most Americans left Japan. The Irwins, however, decided to become Japanese citizens and remained in Japan. They even changed their family name to "Aruin" with kanji characters (有院). In 1942, Bella adopted the Japanese name of "Aruin Bera" in kanji characters (有院遍良). Yukiko subsequently had difficulty explaining to her professors about her last name's unusual kanji. One professor helped her save face in front of the class by saying that there may be one place in Kyushu where her name was common. From then on, that's how Yukiko explained it–that her hometown was in Kyushu.

Yukiko decided to major in Japanese literature to suppress her Americaness and live like a pure Japanese. To look more Japanese, she even dyed her dark-brown hair black and tanned her white face in the sun.

All the Christian churches, mission schools, and missionaries were looked down upon by the Japanese public and military. School teachers were forced to teach their students that the emperor was a living god, and young people were brainwashed to die for the emperor. The Japanese believed that Japan would undoubtedly win the war.

Provisions became scarce and even the Irwins struggled to get food. Yukiko stood in line for hours for food rations. When her Aunt Agnes, who lived near Kamakura, once scrounged for small fish and seaweed on a beach in Katase, some local children threw rocks at her and told her to go back to America.

The Irwin family was viewed with suspicion by Japanese authorities. Robert Jr.'s home was searched by the military police, who barged into his home with their shoes on, trampling on the tatami mats. They ransacked the house and confiscated whisky, as his young sons John and Charles stood by terrified.

The war years were especially tough on Bella who had been running the Irwin Gyokusei school in Tokyo. Bella was constantly pressured and harassed by the Japanese military to sell her school property to be used for military purposes.

Eventually, her preschool had to be closed because the children were forced to evacuate to rural areas as Japan was being bombed. The enrollment of preschool teacher trainees also dwindled, and Bella had financial difficulty operating the large school.

Bella once told her few preschool teacher students: "I shall die with my school," and she never went into a bomb shelter while teaching. However, the bombings got worse, and one of Bella's students was killed by a bomb while commuting to school. Bella was finally forced to sell her school for almost nothing to a military equipment company, and she lost everything, including all the furniture she so treasured from her Kojimachi home. The school had been Bella's dream and passion for many years, her life and reason for living, and suddenly, it was gone. Bella then evacuated to the Takechi family's small villa in Nagaoka, Izu Peninsula.

Yukiko and her college classmates could no longer study either. At first, they underwent bombing drills and dug up the lawn with foxholes. After the U.S. defeated the Japanese in the Marianas in 1944 and B-29s started bombing Japan, Yukiko and other college students were forced to support the war effort.

Yukiko and her classmates were assigned to an armory in Akabane, Tokyo, where she had the boring, clerical job of issuing order slips to companies supplying war supplies. But it was better than a factory job where workers would get dirty from machinery oil.

Malnutrition and stress also affected Yukiko's health. She writes that her period stopped, and that she suffered from intestinal catarrh. Her futon and tatami mats at home were infested with fleas, which bit her all over. At the armory, her favorite time was lunch, when she could eat a full bowl of rice, sometimes with confections like manju and daifuku mochi.

Yukiko's brother Takeo was drafted into the Japanese army and sent to Manchuria as a private. He was certain of Japan's victory and was absolutely willing to fight for the emperor. He knew nothing of the horrors of war. Sadly, Yukiko never saw him alive again. It wasn't until 1947 that Yukiko was informed that Takeo had supposedly died of tetanus in a Manchurian field hospital on January 27, 1946. For Yukiko, Takeo had left his hair and fingernail clippings and a will for Yukiko to inherit all his assets. Yukiko buried his hair and fingernail clippings in the grave of their father Richard at Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo.

After the war, the Japanese believed that U.S. Occupation troops would rape all young Japanese women. Yukiko feared this as well after a professor sent his wife and daughter to the countryside just in case. Many Japanese also admitted that they thought the war was a mistake or that they knew Japan would lose. Under the direction of General Douglas MacArthur, the Japanese quietly obeyed U.S. Occupation authorities. Yukiko moved to Izu, Shizuoka to live with her Aunt Bella.

Post-war years and grandchildren

After the war, Bella started a Sunday School for local children in Izu. Yukiko and Bella lived together in Izu for a few months before Bella went back to Tokyo and declared that she would restart her school at age 62. She rented a small room in the back of a church that her mother had built and restarted her school there.

In 1947, the school reorganized as Irwin Gakuen in accordance with Japan's education reforms, with Bella serving as its first director and principal. In 1952, the school moved to its present location in Suginami Ward, Tokyo. In 2016, Irwin Gakuen celebrated its 100th anniversary.

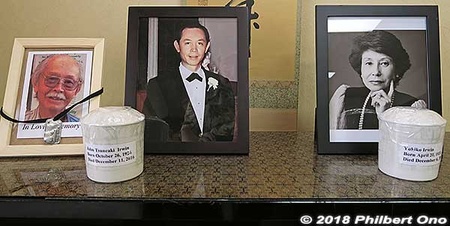

Irwin's three surviving grandchildren all eventually moved to the United States. John Tsuneaki Irwin (1926–2016) and his brother Charles (1928-2018) lived in California. In 1985, John donated 237 English documents, 122 Japanese documents, and 10 French documents that he had inherited from Irwin to the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. In 2012, he donated to Iolani Palace in Honolulu a few medals from the Japanese and Hawaiian governments awarded to Robert Walker Irwin and a few letters from King Kalakaua.

Granddaughter Yukiko graduated from Tokyo Women's Christian College in 1945 with a B.A. in Japanese Literature. She studied shiatsu and was certified as a shiatsu therapist by the Japanese Health and Welfare Ministry.

Yukiko moved to the U.S. in 1953 to attend the Indiana University School of Social Welfare, from which she received a B.A. degree in 1955. She eventually worked as a licensed shiatsu therapist in New York by 1964. Her shiatsu clientele included prominent people such as New York business leaders and European royalty. She wrote an acclaimed 1976 book about shiatsu, Shiatzu: Japanese Finger Pressure for Energy, Sexual Vitality and Relief from Tension and Pain.

She joined The Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence and when she attended her first meeting in the early 1970s, members were surprised to see an Asian woman being a Benjamin Franklin descendant. In 1988, she published her autobiography and a history of the Irwin family in her book, Franklin no Kajitsu (Fruits of Franklin).

She always strove to be a bridge between Japan and America. She died in New York in 2014 and her ashes were buried in the Catskill Mountains. Her gravestone bears the inscription, "Descendant of Benjamin Franklin and Ardent Proponent of Close Relations between the United States of America and Japan."

On August 11, 2018 at Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo, a ceremony was held to bury a portion of the ashes of grandchildren John Tsuneaki (in mother Tsuneko's grave) and Yukiko (in father Richard's grave) at the Irwin family grave as they had requested.

Although Robert Walker and Iki Irwin no longer have any lineal descendants, their estate continues to be managed by the Yukiko Irwin Trust and by their late grandson Charles' adopted son Bob Irwin, both in the United States.

© 2020 Philbert Ono