How did your parents’ activism impact you, your siblings, and entire family? For example, your brother Guy was very influential in helping at-risk youth up until his untimely passing.

Our parents set examples for us between my father’s acts of compassion, in his personal relationships, and my mother’s community work as a teacher and civil rights activist.

Guy followed my mother’s example of working with young people. He spent years counseling at-risk youth, some of whom had been involved in gangs. Guy also resembled my father in that he earned the respect of young people through compassion: he invested in them and listened to their stories, took them out to eat when they missed meals at home, and found housing and jobs for young men struggling with homelessness and transitioning away from gangs.

Guy understood that young people lacking acceptance or structure at school or in other aspects of their lives might turn to gangs. He helped young people find the acceptance and support they needed by encouraging them to focus on improving their communities, finding peace within themselves, and taking pride in their culture.

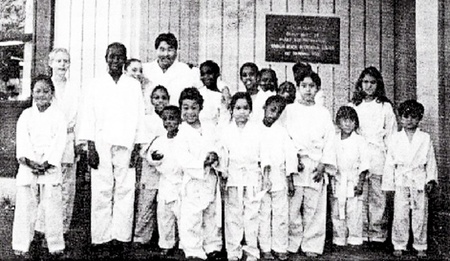

He and my brother Rollie ran a volunteer martial arts program at Rainier Beach Community Center and used positive affirmations to help their young students, instructing them to repeat mantras about doing well in school, respecting their parents, staying away from gangs and drugs, and building personal strength through peace.

My brother Paul has similarly followed my mother’s example. Paul continues to teach the martial arts program at Rainier Beach Community Center, which has been offered to young people for over thirty years. He has devoted his career to teaching math, harnessing his passion for helping students from underserved communities.

My sister Marie has had an impactful career in public service. She is a strong voice for equity in workforce development.

You have always held important leadership positions and were a strong leader during the 1960’s and 1970’s and beyond. What was it like during those intense times and what were some of your successes?

I first got involved in student activism at Garfield High School with the Black Power movement and the school desegregation efforts, AAPI empowerment, and anti-war demonstrations. I was motivated by the principles of peace and racial justice instilled by my parents, and the examples set by mentors like Sharon Fujii, Dolores Sibonga, and Ruth Woo. They felt that the work of improving our communities and our country is never finished.

When I started at the University of Washington, I joined the ongoing student activism against racism, poverty, and the Vietnam War. I have many memories of joining demonstrations and protests: marching on the freeway to protest the US invasion of Cambodia, rallying in support of Indian treaty rights, and demonstrating in front of the Kingdome with Uncle Bob Santos to call attention to stadium commercial interests that threatened to displace the International District.

The goal of these demonstrations was to attain a critical mass of people power to force our issues into conventional mainstream awareness, to quite literally stand up for what we believe in. At demonstrations and organizing meetings, I developed friendships with fellow Asian-American, African-American, Chicano, and Native-American activists.

We worked together to develop strategies for advancing social and systemic change in our communities. For example, Guy and I joined the Native activists’ “fish-in” occupation of Frank’s Landing along the Nisqually River. The occupation was organized to protest numerous arrests of Native-American fishermen at Frank’s Landing who had been targeted by state authorities. These arrests violated a 100-year-old treaty that protected Native fishing rights. The occupation prompted a federal lawsuit that concluded with the Boldt Decision restoring the fishing rights the tribes were entitled to. Joining this work gave me a way to identify with the struggles of others, lessening the divisions there were between us and enhancing our shared beliefs.

In the late 1970’s and early 80’s, I served as an aide to Congressman Mike Lowry, channeling the energy of activism into legislative action. Lowry championed direct compensation for the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. As a member of his staff, I had the opportunity to contribute to the burgeoning movement for redress. The summer and fall of 1979, we organized a small campaign to galvanize support for Lowry’s direct compensation bill, HR 5977, the World War II Japanese-American Human Rights Violations Redress Act.

We communicated with staff in other offices to get co-sponsors for the bill. I had regular strategizing calls with redress leader Cherry Kinoshita (Seattle), late at night in my Washington D.C. apartment. I’d then return to the office and slip “Dear Colleague” letters under the doors of other House member offices, often with help from Phil Tajitsu Nash, a well-known Sansei civil rights lawyer. In total, we contacted over 100 Members of Congress. My colleague, Kathy Halley, was critical to securing the support of the Congressional Black Caucus, which was beginning to discuss reparations for the enslavement of African-Americans—a debt which is still long overdue.

Our bill proposing direct compensation was followed by another bill, supported by the Nikkei congressmen, that proposed a preliminary step of commissioning a study of the incarceration. This made passage of the commission bill more likely. And while our bill didn’t survive, the principle—that the US government was obligated to redress its wrong—eventually became law, ten years later, in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

The redress movement was a monumental achievement. My involvement ended after my three-year tenure in Congressman Lowry’s office (Seattle, 1978; D.C., 1979-1980), but other advocates persisted. They refused to let the passage of time silence the call for the US government to make a substantive apology.

There have been far too many episodes of our government’s failure to preserve and protect the dignity and life of all people. I protested in opposition to many such episodes of injustice. And there is no amount of money, no apology forceful enough that can repair these harms. But the redress movement, the occupation of Frank’s Landing, and many other gains achieved by activists still give me hope in the power of collective action to successfully pursue justice.

What do you think about the youth and young leaders today leading the Black Lives Matter and other movements for racial and societal change? Does it seem different now than at the height of the civil rights movement in the 60’s and 70’s?

Today’s Black Lives Matter movement reminds us that the changes we demanded decades ago have been incremental and our democratic ideals have yet to be fully realized. The deaths of Jacob Blake, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Charleena Lyles, John T. Williams, Tommy Le, and many more are a direct result of decades of unaddressed inequality and racism.

I am inspired by the young Black leaders of the movement who are organizing with urgency to enact transformational change. The popular maxim chanted at many protests I attended as a young activist—justice delayed is justice denied—is still painfully true today.

A significant similarity between today’s movement and the civil rights movement of the 60’s and 70’s is the young people of color who are turning out in masses to hold our country accountable to live up to our founding ideals. Young people led the civil rights movement of the 60’s and 70’s and they are at the forefront of the Black Lives Matter movement today, demanding change through protest and civil disobedience. It is what the late civil rights icon, John Lewis, would call “good trouble, necessary trouble.”

The Black Lives Matter movement gives me hope because I believe our future depends on young people claiming a stake in moving towards a world in which the full humanity and dignity of all people are respected.

Read the interview with Ruthann’s daughter, Mika Kurose Rothman >>

*This article was originally published in the North American Post on September 11, 2020.

© 2020 Elaine Ikoma Ko / The North American Post