One useful study for understanding Japanese American history would focus on “power couples,” that is, spouses or long-term romantic partners who are both accomplished figures in their own right. Perhaps the classic case in this regard is that of the Inouyes. Daniel Inouye was U.S. Senator from Hawaii for half a century. Irene Hirano Inouye, his wife, was a community leader and the founding CEO of the Japanese American National Museum. They made a formidable team.

On a more modest level, midcentury New York City, with its open, cosmopolitan culture, attracted a number of artistic and literary Nikkei power couples: Taro and Mitsu Yashima; Charles Kikuchi and Yuriko Amemiya; Joe Oyama and Asami Kawachi; Ken Nishi and Setsuko Matsunaga Nishi; Eitaro and Ayako Ishigaki; Steve ad Taxie Wada, and (briefly) Larry and Guyo Tajiri.

I have come across a less-remembered example of such a New York couple, Bunji and Kimi Gengo Tagawa. They met as students at Cornell University, moved to the Big Apple and remained together there for almost sixty years, during which time they each made their mark as creative artists.

Kimi Tagawa, the older of the pair, was the first to acquire fame. Born Kimi Gengo in Holualoa, Hawaii on April 4, 1903, she was the Nisei daughter of Yasushige Gengo, a Japanese immigrant writer and schoolteacher, and his wife Chiye. Kimi moved with her family early in life to Suisun City, California, where Kimi attended Fairfield High School.

In the early 1920s the family relocated east to Ithaca, New York. Though the reasons for the move are not clear, it is possible that the move was undertaken so that Kimi could attend Cornell University (The Asai family, the town’s only other Japanese residents, relocated to Ithaca in 1918 for just that reason--all nine Asai children ultimately studied at Cornell). Whatever the case, Kimi enrolled at Cornell University—in the process becoming one of the earliest Nisei women collegians.

In 1926, she published her first verses in The Columns, a Cornell Literary magazine. Among her works was a verse translation of Rentaro Taki’s The Moon on the Ruined Castle. She went on to submit a set of her poems for the James M. Morrison Prize, a Cornell literary award. Twice, in 1929 and 1930, was selected as joint awardee. In 1929 she likewise was awarded Honorable Mention for the Bynner Prize from Poetry Magazine.

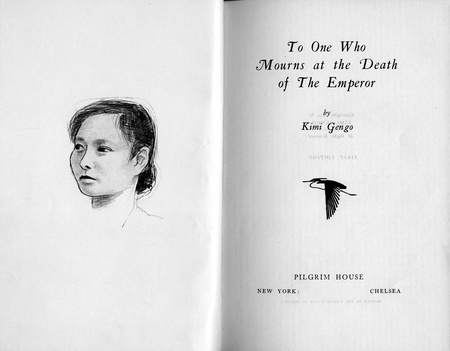

Once engaged in Cornell literary circles, Kimi Gengo became acquainted with Philip Freund, who would later become a distinguished writer and theater historian. Although Freund was just 16 years old when he entered Cornell, he distinguished himself for his literary interests, won a story prize, and rose to the position of editor of the Cornell Literary Magazine. After graduating with an MA in 1932, Freund joined forces with a circle of friends and started his own small publishing firm, Pilgrim House, in order to promote the work of young writers. Gengo was one of the first to be called upon.

In December 1933, the firm published a slim volume of verse by Gengo, entitled To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor. After Kathleen Tamagawa’s memoir Holy Prayers in a Horse’s Ear, which appeared the previous year, it was the first published book by a Nisei woman.The volume was made up of several sections. The first section, which included the title poem and such works as “A Japanese Artist to His Print,” directly evoked Asian themes. Conversely, the following sections were composed of brief free-verse compositions with terse titles such as “rain” and “Ashes.” They showed a certain resonance with Haku and Tanka, as well as with American modernist poetry. Two examples:

RETICENCE

Be bold, my heart.

And tell your lover.

All thoughts are told, but this:

Eternal loneliness.BETRAYAL

Beauty

Has betrayed me.

Pressed his proud fingers

On my eyes and lips. and left me

The last section of the work, “Translations,” was made up of a selection of Gengo’s English renderings of Japanese poems (including hokkus and tankas by the author’s father, identified as “Tessu Gengo”) as well as a passage from The Iliad.

In an Introduction to the book, Philip Freund underlined the work’s double-sidedness. Pointing to the elements of Japanese style in the inspiration for Gengo’s poems, he credited the author with having “combined the liveliness of Japanese subject matter and feeling, with the maturer development and searching that characterizes and makes possible the great romantic English poets.”

Freund claimed that she thus could serve as a fresh model for “poets in Japan, and young Japanese students in America” stultified by tradition. Freund was clearly aware of Gengo’s wariness over Orientalized readings of her work, but found them irresistable. “The number of Miss Gengo’s poems that are frankly Japanese is surprisingly small. Kimi Gengo is a gracious American, reticent whenever an opportunity presents itself to exploit her racial heritage. But in any artist worthy of the name, and sensitive as art demands, a racial heritage can hardly be denied.”

Gengo’s book attracted a wide spectrum of reviews, many of which were even starker than Freund in their discussion of Gengo’s hybridity and their use of Orientalist cliché. A reviewer in an Ithaca newspaper stated of Gengo, “Her poems are delicate lyrics, which could have been written only by a deeply sensitive and honest temperament combined with an Oriental racial heritage and an American education.”

Percy Hutchinson, writing in the New York Times Book Review, asserted, “There is no profusion here; for it is not in the way of Nippon’s art to be profuse. Each of these poems is a print, an intaglio; in this each is purely Japanese. On the other hand, there is a most interesting occidental change; reticently, almost shyly, Miss Gengo permits an emotional infusion which is western, not Japanese, with the result that her verses are unique, a blend of the distillates of two cultures." Poetry Review‘s critic added, “In the poetry of Kimi Gengo is denied the long acceptance in regard to the East and the West — that never the twain shall meet.”

Other reviewers criticized Gengo in racialized terms. The Saturday Review of Literature stated flatly, “A Japanese woman writing in English. Not very memorable.” A critic in The Nation similarly described the author as “a Japanese woman living now in New York.” Like Freund, the reviewer pointed to the author’s cultural hybridity. “Strange as it may seem, her poetry is much better when it turns from Oriental forms or ideas to the expression of personal emotions in the precise English lyric form.” The La Crosse Tribune referred to the volume as “poems by an Americanized Japanese woman who, while using our verse forms, gives us Japanese subject matter and feeling.”

A rare exception to the Orientalist discourse was offered by a critic in the New York Herald Tribune, who asserted, “This young poet is a Japanese woman brought up and educated in America. The book is therefore a study of how a poet may be influenced by environment. And the best of Miss Gengo’s lyrics are not Japanese, but distinctly American.”

By the time that her book was published, Gengo had begun a new life. While at Cornell, she had met a Japanese student, Bunji Tagawa, who was similarly active in campus literary and artistic circles, and begun going out with him. Following her graduation (and a stint working as a secretary and stenographer for the Farm Bureau) Gengo moved to Brooklyn, New York. There she and Tagawa were married in 1932. Their daughter Ikuyo Tagawa (later Ikuo Tagawa-Garber) was born later that same year.

In the period that followed their marriage, the Tagawas moved to MacDougal Street in New York’s Greenwich Village. Kimi Tagawa worked for the local office of the Home Relief Bureau. In 1940 she was listed as a social investigator for the New York City Department of Welfare. She does not seem to have been active in producing literature, although author-activist Ayako Ishigaki [Haru Matsui] thanked her for assistance in the writing of Ishigaki’s 1940 memoir Restless Wave.

The Tagawas were powerfully affected by the coming of World War II. Although as New York residents they were not subjected to mass removal, Bunji Tagawa, as a Japanese national, was restricted by a curfew (and according to a family legend, placed under house arrest for a time). Kimi, as a Nisei, was unhindered in her movements, and could thus more easily shop for the family and serve as courier for her husband in his work.

At some point during this period, Kimi Tagawa became a clerical staff member of the national board of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). In 1943 she attended a conference of the National YWCA in Hartford, Connecticut. There she spoke of the community aspects of the YWCA’s work dealing principally with problems of Japanese American resettlers and of African Americans. She turned to literature to push for racial tolerance.

According to historian Abigail Sara Lewis, in the fall of 1943 she began publishing in the YWCA magazine The Bookshelf a series of three fictional vignettes about a young Japanese American girl named Fuji Mae, who lived in a regular American community. In the three vignettes, “Fuji Mae Wants to Know,” “Alice Visits Fuji Mae,” and “Fuji Mae Tries to Understand,” her young heroine learns about food, education, dating, and family relationships in Japan and the United States. In the last installment, a Nisei boy newly resettled out of camp gives a presentation at Fuji Mae’s school. Tagawa thereby was able to educate her readers about Japanese immigration, anti-Japanese prejudice and mass confinement.

After World War II, Kimi Gengo Tagawa does not seem to have continued her literature career. She worked for a time as a social worker for New York City, but was hindered by workplace injuries. She also served as an instructor at the New York school of Social Work during 1950-52. In the years after the war, the couple moved to Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, where Kimi Tagawa served as an officer of the local block association. She died in December 1987.

© 2020 Greg Robinson