“Close to 800 dry glass negatives abandoned by the Matsubuchi studio reappeared in the mid-1980s in garage sales, and were recognized and collected by Cumberland residents, Mr. Frank Kothlow, Mrs. Flowers and Jim Small. Thanks to the foresight of Dale Reeves, the former director of the Cumberland Museum, the prints from these negatives are now located in the Museum’s Archives as a research collection,” taken from Shashin: Japanese Canadian Photography to 1942 exhibition catalogue, Grace Eiko Thomson, Japanese Canadian National Museum, 2004

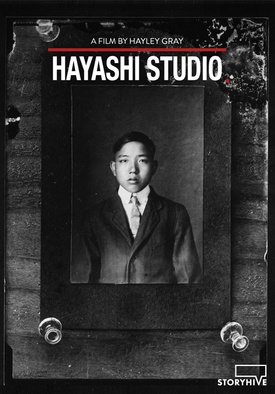

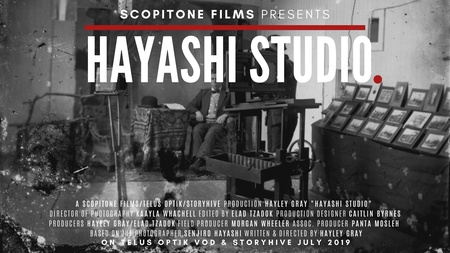

After watching Hayley Gray’s remarkable “Hayashi Studio” documentary, I stumbled out into bright afternoon sunshine wondering about how well my own family’s BC history could be told through photographs?

The remarkable story of Senjiro Hayashi (1880-1931) was saved from the Cumberland dump, literally, when glass negatives that he, Mr. Kitamura and Tokitaro Matsubushi created were being sold at garage sales in the 1980s.

Senjiro settled, then, in Cumberland, a coal-mining town on Vancouver Island, as a photographer in 1903. In 1910, he apprenticed with Shuzo Fujiwara at Fujiwara Photo Studio and eventually set up his own shop in 1912 after which time he called his wife and son from Japan. In 1913, he opened his Willard Block studio in downtown Cumberland. It was taken over by a Mr. Kitamura in 1919 and then Tokitaro Matsubushi in 1923. Closing briefly, it reopened and operated until 1941 when the studio was commissioned to take photos for government registration cards just prior to the mass expulsion in 1942.

Photographs are the missing fragments of our story. Recently, as my own Dad entered a long term retirement home, we are beginning to go through a lifetime of “stuff”. The dusty old black and white snapshots I flip through really begin in the 1960s. There is virtually no evidence of my parents’ childhoods. I have never seen a picture of Mom’s dad who died in Slocan, BC during the internment years nor have I ever seen a picture of Dad’s birth mom, Tami (nee Imai) who died of TB in the 1930s. Did they ever really exist?

A few JC friends have roots in Cumberland. George Doi of Langley, BC, remembers: “My parents moved from Cumberland in the late 1920s to Royston three or four miles away and that is where I was born. I don’t have much memory of Cumberland. The only Japanese I knew there was Mr. Kanamoto, a well known professional gardener/landscaper. Before moving to Toronto in 1945, Mrs Kanamoto gave my Mom a Japanese-English dictionary to give to me. I still have it: an Inouye dictionary, published in 1909. It comes in handy because a lot of obsolete words are in there like ‘jibiki’ (dictionary). Today ‘jisho’ is used.”

David Iwaasa lives in Vancouver with wife Jane (nee Kadonaga). The former Albertan, recalling his connection to Cumberland, said: “My great uncle, Matsutaro Iwaasa (he spelled it ‘Iwasa’, but that is incorrect), first came to Cumberland in around 1894. Some four years later, my paternal grandfather, Kojun Iwaasa, went to Cumberland to live with his uncle and ostensibly to help run the family general store which was located in No. 1 Japantown. My grandfather, Kojun, didn’t really live in Cumberland very long - maybe a cumulative two or three years, but the Matsutaro family was one of the leading families in the community. Matsutaro was quite the entrepreneur and was also involved in the Royston lumber company as well as a number of other local enterprises. Some other second cousins also passed through Cumberland thanks to Matsutaro being there. Jane’s family had a farm on Mayne Island. Right now, my uncle, Raymond Iwaasa, is living nearby at Qualicum Beach and volunteers at the Cumberland Museum.”

Fragments of memory though they may be, precious they are.

As I reread W. Peter Ward’s powerful White Canada Forever (McGill-Queen’s University Press), I am reminded about the necessity of remembering and passing on the legacy of our stories on to future generations with our own voices.

Paused, mid stride now, walking down Hastings St., I wonder how many more Hayashi Studio stories there are out there? Truly, each of our families has one. So does each community throughout the City of Vancouver like Marpole, Kitsilano, Fairview, places on Vancouver Island like Victoria, Chemainus, and Tofino, up and down the Sunshine Coast and north to the Queen Charlotte Islands, throughout the Gulf Islands (e.g., Bowen and Salt Spring islands) and into interior communities like Oyama (named for Japanese Prince Iwao Oyama (1842-1916), and Kelowna, where JCs lived and worked too.

* * * * *

Can we begin with a bit of personal background? Where did you grow up and what was your initial contact with Japanese Canadians?

I grew up in Kingston, Ontario. I didn’t have an understanding of the Japanese community in Canada really until I moved to Vancouver. As I got to know more Japanese-Canadians and Japanese newcomers I began to understand that the experience, perspective, and history of WWII was very different than what I was taught.

When did you become aware of what had happened to JCs during WW2? Reaction?

When I first started working with Mayumi Yoshida I began to learn more. One project we worked on was a poetry reading to commemorate 70 years since the end of the War in the Pacific. Reading and hearing those poems and letters from Japanese and Ally troops really made me reflect on the Japanese experience of World War 2. I think it was only once I began to research Hayashi’s photos and history did I really begin to learn the Japanese Canadian history of World War 2.

Did you ever talk to your parents or grandparents about internment? Did they have any connection to the JC community?

Honestly, not until they saw Hayashi Studio. I remember very distinctly my grandmother sharing her outrage with how the Japanese-Canadian community was treated after I showed her the film.

How did you hear about the Cumberland community? What was your initial reaction on learning that there was a community of JCs there?

It was such a weird set of circumstances that got me to Hayashi. A friend of mine who created populousmap.com told me that she needed to check out Cumberland, that she thought they had done a better job of archiving their diverse communities than many other spaces. She asked me to come with her. I had only been to Vancouver Island once or twice before this. But as soon as I saw the photos I was so stuck, I deeply wanted to know more, more about these people, their lives here, and why they weren’t here anymore. Then seeing the townsite where so many families lived now fallow fields was so heart wrenching.

So what inspired you to take this on as a documentary project?

Seeing Hayashi’s photos, it really made me think about my upbringing, my history classes, and my understanding of Canada. It made me think how little I knew, not just about Japanese-Canadian internment, but about the 65 years of Japanese-Canadian history before internment. I thought, maybe I could make a documentary that could help those who didn’t know the Japanese Canadian history (like myself) understand it better. Also the photos. They are so striking and beautiful, each one makes me want to get to know its subject. Lastly, I wanted people to understand that there are diverse histories in Canada. We get to know the Cumberland Japanese Canadian community because Hayashi was there documenting, but how many other Japanese Canadian communities will we never get to know like this because there wasn’t a photographer in the community taking photos?

Can you talk a bit about the team you worked with?

Absolutely, I worked closely with my amazing editor and producer Elad Tzadok, he brought the style to the film, he has a keen eye for story and a love of vintage cameras which came in handy. Kaayla Whachell is one of my favourite cinematographers in Canada, together we established the visual style of the film and how we would use visuals to tell the story. I think the best thing about our team is that they all shared a love of history in interviews after I finished I’d ask the team if they had additional questions and they had so many thoughtful questions and we’re so invested in the story and film.

How did you locate the key people? Was Grace the instigator? The anthropologist was extremely insightful….

Laura, the anthropologist, is a friend, and the person who instilled in me a love of BC history and my desire to learn more diverse histories. I was really lucky to connect with the amazing teams at the Nikkei Centre and The Cumberland Museum and Archives, they pointed me to the people we connected with in the film.

Can you talk a bit about your experience with Grace Eiko Thomson?

The first time I met Grace I came to her apartment to learn more about Shashin and her curation of Hayashi’s photos. I was nervous and excited, very quickly I realized I had found a good friend as we drank too much green tea and got into deep discussions about colonialism, chauvinism, racism and of course, the photos, her research, and the life experiences that inspired her curation. Grace is such a force, and I know so many people over the years who were looking to learn more about Japanese-Canadian history, like me, would spend afternoons at Grace’s kitchen table pouring over her research and learning from her. Hayashi Studio would not have the context and nuance it does without her. I am greatly indebted to Grace not only for the film, but for deepening my understanding of the Japanese Canadian experience.

When I met with Grace she really gave me the strength to move forward with the production, she told me, “I wanted my curation to be the beginning of the conversation, I want your film to continue it.” I actually wasn’t sure when I started the film if there were any Hayashi’s left in BC, I stumbled across an interview with Senjiro’s youngest son, in it he named his grandchildren, I found one of them on Facebook, very lucky.

Can you briefly tell us who they are and how their stories are connected to Cumberland?

Laura Cuthbert is an anthropologist with a deep understanding of the diverse history of BC. Grace Eiko Thomson was the first curator of the Hayashi photos. Douglas Sadao Aoki is a descendant of the Cumberland Japanese-Canadian Community, his grandparents ran the Japanese Language School. Florence Bell is an amazing Cumberland Local with deep knowledge of their Japanese Community. And of course, Brent and Sharon Hayashi are Hayashi’s descendants!

As a non-JC, do you think that this frees you to some extent in how you can tell the story? Can you describe some of the feedback that you have received?

I thought for a long time about should I tell this story, as I’m not a part of the community, Grace’s support was really important in that decision. I decided I could tell it if I told it from the perspective of a Canadian wanting to know more about our collective past. The feedback has been the most rewarding part of the film, I’ve had so many people both in and outside of the community tell me how much the film has meant to them. At our last screening, a woman told me her daughter wants to be an anthropologist and told her it was her favourite film. At another screening I had someone tell me that she felt I had uncovered a cultural genocide, but Japanese Canadian and diverse communities have been speaking to this for a long time, but I’m glad the film allowed more people to understand.

What is the history lesson here? Advice about keeping family pictures?

Keep all of your family pictures and donate them to the archives! Interview your grandparents! I think one big thing is that history is our collective understanding of the past, and our communities and social histories are just as important as any politicians. The other is, our history is diverse, it just wasn’t documented equally.

Have you been showing the doc around? Where? Are you coming to Toronto?

The documentary is available online, on Telus Optik VOD in Alberta and BC and on Air Canada, we screened in at the Powell Street Festival and the World Community Festival and are planning to screen in Toronto, TBA.

As the director, is there a lesson-to-be-learned that you want viewers to go away with?

Almost every town in BC had a Japanese, Chinese and Black settlement, diverse communities have been part of this country since the beginning, their histories have been erased and we need to do what we can to find and share them before it’s too late.

I’m working on another documentary with the National Film Board examining other unarchived pieces of BC’s history.

View the documentary at hayashistudio.com.

© 2020 Norm Ibuki