“What you are feeling is grief,” says the article from Harvard Business Review. And yes, living in COVID-19 in Washington State, March 2020 feels like a kind of grief, even though I have grieved before. But the waking up to a profoundly altered reality each day, each wave a fresh infusion of loss, or a looming reminder of losses to come—grief feels like an appropriate description.

Honestly, the way that I dealt with grief in the past was to avoid. I avoided through hyperactivity, through overachievement, anything to avoid feeling grief. Learning the skill of grieving has really taken me these ten years that I’ve been actively writing about it.

If, as my friend Ann Putnam says, “all loss evokes other loss,” I turned back again to two of the central losses that drive much of my life: the loss of my father when I was 10 years old, and the community loss that is Japanese American wartime incarceration. Both losses meet in my father’s unpublished book, Daruma: The Indomitable Spirit. It’s a book that he wrote (but never published) about his wartime experience, his family’s incarceration at Arboga Assembly Center and then Tule Lake. The book spans the years from 1941 to 1945, from when he was 10 to when he was 14. I’ve been working on a larger project for years that will publish the book at last.

Over the years the book has come to mean many things to me. A valuable historical document that tells of a young Nisei male’s memories of camp, especially in the controversial Tule Lake, before and after its history as a segregation center. An extended hearing of my father’s voice, much of it recorded in the years just before I was born.

There are ways, I’ve discovered, that I can index the book for myself: different ways that I can look through the entire manuscript, creating different maps or paths. I’ve indexed it for action, summarizing each chapter according to the “action” of each one. I’ve looked at the book for examples of what my dad was feeling about camp as a young adolescent. I’ve looked at the points where he and his family were separated, due to my grandfather’s arrest in March of 1943. There are emotional points and plot points. But as I’ve written elsewhere, one of the most interesting portraits that emerges in my father’s book is that of my Issei grandfather, Junichi Nimura.

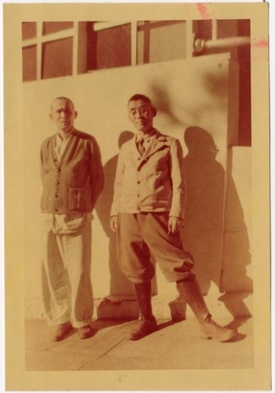

I went to my father’s book again in this difficult time because I wanted reassurance, leadership, resilience, resistance. There are other stories that I will tell about my grandfather in the future, because I’m still learning about him. I don’t have many pictures of my grandfather; he died nearly a decade before I was born. The pictures I do have are formal, sepia. My grandfather sits, stoic, nearly expressionless. The pictures are of him postwar, most of his six children grown up, my oldest auntie with a child of her own. If I didn’t know better, or hadn’t read my father’s book, I would think that he was humorless, stern. And from what I have heard of his anger, he was indeed stern.

And yet the grandfather in my father’s book is, for the most part, far from that man. He was a lover of nature who missed trees while in camp. He created a watering can for camp gardens by poking holes in the bottom of a coffee can. He was an avid singer, a folk dancer who performed a “Fishermans’ Dance” in camp.

And he loved to create things for a community. In my father’s book, the story I turn to today is the chapter called “Mochi.” According to my father, who was 13 at the time, my grandfather decided to have mochi on Christmas for Block 45, their block. To make mochi outside of camp, in “normal” conditions, is an all-day, multiperson undertaking. To make mochi inside camp, without the proper equipment? Nearly unthinkable, or so it would seem.

How to obtain the special rice? Rice growers did not normally grow rice for mochi. My grandfather found a Japanese wholesaler in San Francisco who shipped his stock to camp, close to 400 pounds of it. He asked the families of Block 45 to agree on portions and contributions in order to pay for it.

How to get the proper equipment for pounding the rice and cooking the rice? My grandfather found orange branches for the staffs and mallets. Scrap lumber, always a popular material, was used for the rice cooker. He adapted a galvanized wash tub, cutting a hole in the sides and reinforcing it with steel rods; this one was turned upside down so that a fire could burn underneath it. A new wash tub with water was placed on top of this tub, creating a sort of makeshift stove. As luck would have it, an Issei neighbor on the block, Mr. Takayama, was an expert in building rice cookers. He created a rice cooker that would cook 5 pounds of rice at a time, using wooden pieces that fitted together like a puzzle. When my father asked why he did not use nails, Takayama-san explained that nails would only rust with all the steam. The cooker used several sections of bamboo mesh that prevented the rice from falling through. Bamboo would have been a precious commodity, but somehow my grandfather persuaded the people of the block to contribute enough.

During the mochitsuki, my father says, my grandfather sang a drinking song to help the mochi pounding go smoothly. After a request on social media with the lyrics of the first line, I found out from friends and relatives that it’s called Kagoshima Ohara Bushi. My friend Etsuko sends me a link to a recording of the song, which now sounds familiar—it’s a Bon dance! My youngest auntie says that that my grandfather used to sing this song and play it frequently on 78 records.

My father recounts the details for the mochitsuki in loving detail for several pages—it’s a remarkable passage in the book for its specificity some thirty years after camp.

Right now leaders in the Tsuru for Solidarity group are calling for the Japanese American community to remember #IsseiResilience, a way to honor and practice the lessons from our ancestors. Certainly, the Tule Lake mochitsuki of 1944 was an amazing lesson in the resilience of my Issei grandfather. I marvel at his ability to organize people, to inspire his children, to bring together community, to marshal scant resources and use them to their utmost advantage in a time of extreme scarcity.

My father says that his father was a skilled carpenter who took pride in his workmanship, to build things “that last for a lifetime.” How remarkable that my Issei grandfather built a mochitsuki for his community in camp, that his Nisei son would remember it so clearly, that I as his Sansei granddaughter can pass all of this on to my Yonsei daughters.

I am learning many things from the Issei grandfather that I never met, and from my father’s memory of camp. In these difficult times I’m learning that our children will watch how we behave. They will remember how we handled adversity. Decades later they will remember not just what we create in these difficult times—they will remember how we created it, and why.

© 2020 Tamiko Nimura