I caught up with Newfoundland artist David Hayashida on his return home after returning from the BC Internment Camp tour in July.

Like me, he grew up in Ontario far removed from most Japanese Canadians. We were often the only Asians in our schools. And as inheritors of the internment and the Redress legacy, we have spent much of our adult lives figuring out how to become valued members of our mostly-white communities where we grew up clinging on to whatever vestiges of our Japanese ancestry that we could.

As an eastern born and raised JC in Toronto, confronting the multifold meaning of “British Columbia” was and continues to be an important one in terms of constructing my Canadian self. Even now, the first words to come to mind when I hear “BC” are racism, internment, dispossession, Strawberry Hill, and, maybe, enemy alien. Context is important. I’ve come to terms with most of those feelings over the past couple of decades. For the uninitiated, however, I understand all too well that the wall between here and Vancouver is much more than 4000 kilometres. The bigger obstacles are the phantom ones. What might be stopping us from visiting BC? We may wonder how we might be received in BC? Do we really want to confront this family and ugly part of history now? Isn’t it better to just let what happened in BC slide into obscurity?

Dad, 88, had his connection to BC shattered when his family was forced to move and do labour on a sugar beet farm in Manitoba. While he was too young to serve during WW2, and vowing never to return to BC, he joined the Royal Canadian Corp of Signals Regiment in the 1950s. I recently learned that he was supposed to be stationed in Japan, then, at the last minute, was sent to Hanover, Germany where he served for two years. With that chip on his shoulder and even despite being kicked out of an English pub after the war wearing his uniform after they learned that he was of Japanese descent, he’s never doubted his right that he belonged here as a CANADIAN.

Forgive me now for wearing my teacher’s hat for a moment but time has run out for those of us, the children and grandchildren of the survivors of internment, BC racism and the aftermath, to take a stand. Unless we do, we’re certainly doomed. Time is almost up. We simply cannot allow even wider cultural chasms of JCness to grow for younger generations to bridge, especially here in eastern Canada. (When I was in BC, it was wonderful to learn that the Japanese Canadian experience is going to be included in their school curriculum beginning this fall.)

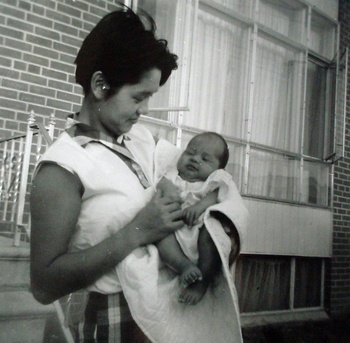

As a middle-aged Sansei I am really worried that the range of our experiences, like my mom’s troubling one, might get lost. I have always known that her’s, Sumiko’s, mental illness could be traced back to the 1942 internment. She apparently showed signs even from a young age where there were no support for kids in internment camp schools. Certainly being in a prison camp, living in a wooden shack with seven siblings and two parents going to a ramshackle school with untrained teachers and no support services like a social worker or child psychologist who could have helped her, didn’t help.

Afterwards, in Hamilton, ON, she saw and talked with the very real spectre of her father, Tatsukuro, 65, who passed away in Slocan City on January 11, 1946. I remember those spooky episodes well. Doctors were never much help. As a kid in doctor waiting rooms, it was always just another new prescription for pills (which she ALWAYS hated taking) or institutionalization when the going got too difficult. Just like Dad and his father who never got over losing his Strawberry Hill farm, Mom never forgave Canada for what it did to the Hayashidas (no relation to David) either. She never returned to New Westminster, BC. These hard stories often get lost in the narrative that we like to tell Canada.

The east-west divide is still a formidable one for many eastern JCs.

Our divided communities are a direct consequence of that heinous “Keep BC White!” campaign whose 1945 anti-JC slogan was “Go East or Go Home”. Truth be known, my relatives never wanted to be exiled east to Winnipeg, Hamilton, Toronto, or Georgetown.

Hats off to Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson (1897-1972; Nobel Prize 1957 winner) who helped to organize the United Nations in the aftermath of WW2. Another Canadian legal scholar and human rights advocate John Peters Humphrey (1905-1995) who wrote the first draft of the 1947 Universal Declaration of Human Rights for the United Nations. Both of these Canadians helped to stop BC’s racist politicians (e.g., Howard Charles Green) freewheeling purge of BC's JCs.

In 1947, the Canadian Citizenship Act came into effect which allowed all Canadians to become citizens of Canada for the first time, no longer British subjects. (Influenced by BC’s racist sentiment, however, the War Measures Act was extended under the National Transitional Emergencies Power Act.) In 1949, the WMA was finally rescinded, and JCs could vote and were free at last to return to live and work in coastal BC. Sure, many returned, but many didn’t or couldn’t, and some vowed never to step foot in BC ever again.

So, like Newfoundland and Labrador artist David Hayashida, 59, going to BC was an important step toward coming to a better understanding of his Japanese Canadianness. As a middle-aged artist, even before going, he had the opportunity to process and express what-internment-means-to-him in a powerful and visceral work to be discussed a little later. The piece that he created for the recent “Being Japanese Canadian…” exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, stands out for me.

Having just returned from BC myself, I share a lot of David’s feelings about racism, the need to speak out about issues that relate to First Nations and JCs, the need to get the language that refers to how our institutions are named and that speak to our collective JC experiences when it is written about with some unanimity once and for all (e.g., Nikkei versus Japanese Canadian), and, importantly, acknowledging that our experience as JC easterners is different (e.g., not so well entrenched and politically connected) but no less meaningful than for our western cousins.

Now here’s David from about as far east in Canada as you can get!

* * * * *

As you are fresh from your BC Internment Camp tour, can we start there?

How was it?

The July 2019 Canadian "Internment Camp" tour was challenging. Even the name of the tour started me thinking. Might it have been a better option to call it the ‘concentration camp’ tour?

When I talk to people about the internment and/or prison camps that JCs were sent to, it is unfortunate but I find far too many people who instinctively think negatively of JCs affected (e.g. ‘oh those people who deserved it or had to be there or surely must have done something wrong’). Where as, whenever I use “concentration camp” instead they seem to immediately get that JCs were innocent people who were unjustly imprisoned.

While I was visiting the camps, I consciously had to force myself not to lose myself only in the heartbreak of those horrific days but to instead embrace the outrage at the injustice and focus on my outlet, creating art to reduce racism in the future.

Can you give us a run down of where you went?

Starting from the National Nikkei Centre in Burnaby, Hastings Park, Friendship Gardens (dedicated to Miyosh “Buddy” Umemura, Alderman 1971-84) in Hope, Tashme, Osoyoos, Greenwood, Christina Lake, Nelson, Slocan Valley, Lemon Creek, Popoff, Bayfarm, Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre and Kohan Garden in New Denver, Sandon, Langham Museum in Kaslo, Kamloops Japanese Cultural Centre, Miyazaki House in Lillooet.

Why did you decide to go?

My father, Kei (Kaye) Hayashida and I had talked about going together for decades. For health reasons he was unable to go at the last minute. (He is thinking about going on the Manitoba Sugar Beet tour in October!)

I was hoping for a better understanding of the physical reality of the sites and to get first-hand thoughts from those who were there during the war era. Many on the bus including myself struggled to reconcile the (reforested) beauty of the locations juxtaposed with what was a concentration camp. I think if one could go back in time and 'visit' during one of the worst winters on record (1942), in severely overcrowded conditions, in uninsulated wooden shacks and with a backdrop of barren, recently logged hillsides, perhaps there would be less of a conundrum.

As this is your first trip to the BC camps, any thoughts?

The trip really crystallized some thoughts and feelings. It should have been obvious to me that racism is just not going away anytime soon. It is a dark undercurrent that is a present danger in 2019, has happened in the past and will happen again in the future. The responsibility to oppose this ongoing threat is not someone else’s problem. It is ours, both mine and yours. Good decisions are made from a real and truthful appraisal of past actions. Wilfully ignoring or failing to honestly evaluate our past mistakes means foolishly repeating the errors of the past.

While Canada has done many good things, the reality is it has also done evil things to many innocent people here in this country including JCs, continues to do evil things to (amongst others) Aboriginal people, and I foresee more injustice in the future. Every country: Canada, Japan, America we all struggle with racism and other wider issues of social justice. I feel one of our jobs as JCs is to try to help educate Canadians on past injustice so we can collectively as a nation choose a different and better path forward.

Any inspiration along the way?

I was not surprised by my digital camera putting focus squares around each bobbing face in our lively tour group. But I physically experienced an intellectual and body shock when photographing the black and white historical images of people from the concentration camps. My camera did the same thing? It puts focused squares around each deceased person’s face as if they might suddenly move and become out of focus. I felt the hair stand up on the back of my neck. Cue the music. For me it was an ‘aha moment’, a sign. They were calling me to action, to continue to try and give voice to the pain of those thousands who can no longer speak for themselves. It reinforced my desire to try and make clear a difficult history that, unfortunately, some would rather remain out of focus.

As long as I can remember, I have had an obsession for collecting rocks and minerals. (I currently live in a province nicknamed “The Rock” so no surprise there.) Naturally on tour I collected BC Jade and other local rocks some found and some purchased. (Many bus tour members might only remember me as that guy, the one who collected pebbles everywhere.) My intention is to try and carve them based on a distillation of this new experience of visiting the JC concentration camps.

Who did you meet?

Dr Jordan Stanger-Ross and Mike Abe of Landscapes of Injustice at the University of Victoria. They were both very interesting. I hope everyone checks out their newsletter.

Can you talk about your own families internment experience?

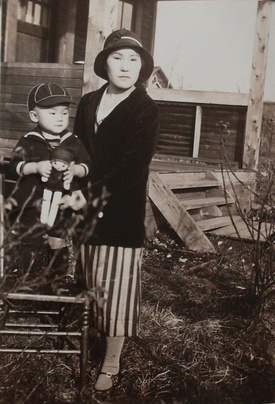

My late mother, Teruye Tsuyuki, and her family were in Lemon Creek while dad’s family, the Hayashidas, were in Popoff.

Did you hear any stories growing up?

A little in the ‘70s but certainly much more after the Redress in 1988. Dad is the story teller in our family. One that dad tells, are of “the vultures” who bought and sold household items, they smelled blood and showed up offering pennies on the dollar for any item of value to the JCs being ethnic cleansed from the BC coast in 1942. Too many took every possible advantage of the injustices, too many stood silent. Thankfully there were a few who offered help during a very dark time for the entire JC community.

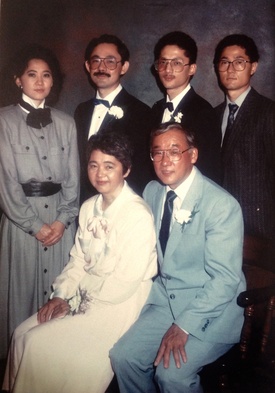

How did your parents end up in Oakville, Ontario?

My dad’s parents had decided to accept the federal government’s “generous“ offer, the certainty of a free one-way trip to the starving, defeated nation of Japan rather than endure endless broken government of Canada promises. Fortunately, his sister Atsuko who was 15 years old, just two years older than my dad, heard the discussion and told dad. Together, incredibly, they stood up to their parents saying they were Canadians and would not be exiled. Rather than break up the family, the parents decided they would all move to Ontario.

© 2019 Norm Ibuki