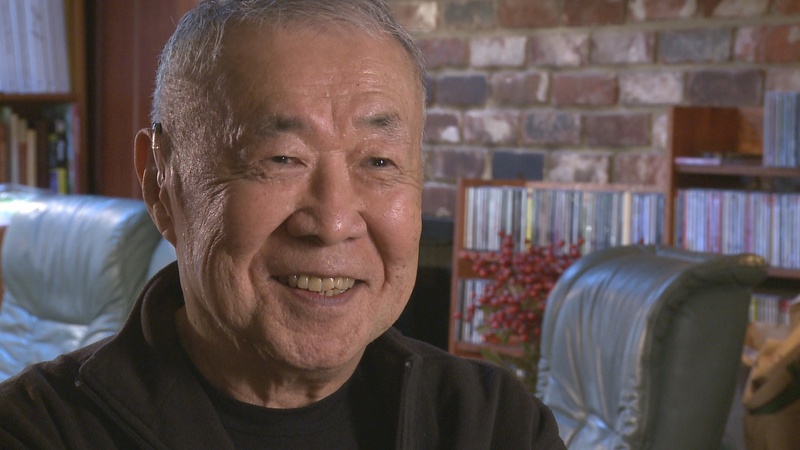

Many notable events of 1969—the first landing on the Moon, the Woodstock Rock Festival, the Stonewall Riots, and the New York Mets World Series victory, among others—have been the subject of widespread commemoration lately, as their respective 50th anniversaries dawn and people take stock of the diverse legacies of that monumental year. Asian American Studies scholars, for their part, are now celebrating the 50th anniversary of the birth of the field. Popular attention has tended to focus on the student strikes at San Francisco State University that ushered in the first Ethnic Studies programs there. Less known is the story of the outstanding Asian American Studies course that debuted that year across the Bay at UC Berkeley, and that of the professor who gave the course, the formidable scholar and advocate Paul Takagi.

Paul Takao Takagi was born in May 1923 in Auburn, California, one of three surviving children of Tomokichi and Yasu Takagi. His younger sister Hannah Tomiko (Takagi) Holmes, who lost her hearing at the age of two, later became a prominent activist. Paul Takagi grew up in the Sacramento Valley, where his father operated a 50-acre strawberry farm (the farm would be seized by the California state government during World War II and sold off for property taxes). He later recalled that he attended a two-room school house, where he encountered supportive public school teachers. He attended Elk Grove High School, where he graduated in 1941, then started junior college in Sacramento.

Soon after, in Spring 1942, the Takagi family was incarcerated at the Manzanar camp. While at Manzanar, the young Takagi was employed as a medical orderly. He was at the camp hospital in December 1942 when Jim Kanagawa, who had been shot by MPs during the so-called “Manzanar riot,” was brought in. Takagi remained on duty overnight as Kanagawa’s life ebbed away amid the inadequate medical facilities. Traumatized by the experience, Takagi left his job and took a position on the editorial staff of the Manzanar Free Press.

In mid-1943, he resettled outside camp. (The rest of the family meanwhile moved to Tule Lake so that Hannah could attend a new school for the deaf that the WRA had opened there, but when the school proved disappointing, they relocated to Chicago). Paul departed Manzanar with the declared goal of attending a trade school in Iowa, but ended up settling instead in Cleveland. There he worked as a “swamper,” loading and unloading trucks. Through his job, he joined an AFL union. “I was happy working out doors and meeting people I've only read about - Jews, Pollocks (not my word, theirs), Greeks, and people from the Ukraine - all of us getting the same pay,” he later recalled.

Not long after arriving in Cleveland, Takagi joined the U.S. Army, and was assigned to the renowned 442nd Regimental Combat team. He underwent basic training at Camp Shelby in Mississippi, but just before his unit was to go overseas, he was transferred to the Military Intelligence School at Fort Snelling. There he specialized in study of German. He was discharged in October 1945, following the end of the Pacific war.

Following his discharge, Takagi enrolled at University of Illinois, with support from the GI Bill. There he experienced discrimination—a writing assignment that Takagi produced on his experience in the hospital at Manzanar received a poor grade from a bigoted professor—which led him to withdraw from the university after a single year. He moved to Chicago to be near his family, and found a job in a milk bottle factory. He later recalled that he would work the late shift, and would then go downtown to frequent bars and listen to music by the jazz bassist Pops Foster and the blues guitarist T-Bone Walker.

In 1947, Takagi moved back to California and completed a Bachelor’s degree in psychology (he was mentored by Timothy Leary, the future professor and LSD advocate, who was then a Berkeley graduate student). In the following years, Takagi married Mary Ann Takagi and had two daughters, Tani and Dana—Dana Y. Takagi would later become a distinguished professor of sociology and Zen priest.

After graduation from Berkeley in 1949, Paul Takagi worked as a prison guard at San Quentin prison, which led ultimately to his becoming a parole officer for the California State Department of Corrections.

In 1952 he was engaged as a deputy probation officer in Alameda County, as part of which he supervised adult offenders placed on probation for felony or misdemeanor convictions. Although he was honored, he later explained, to make history as the first ethnic Japanese probation officer in the state’s history, he increasingly found the work meaningless. Thus he transferred to Los Angeles, where he asked for and received a caseload of people who had gone to prison for heroin possession, sale, or use. His service there caused him to rethink his ideas on race and social control. As he later explained, “The state became alarmed by the drug problem and they picked me - the expert - to conduct a survey... I realized then doing research was what I wanted to do, and I went back to school as a graduate student at Stanford.”

Takagi was already near forty years old when he enrolled at Stanford, but he persevered, and ultimately received his doctorate in Criminology in 1967. Even before he completed his degree, he was recruited by UC Berkeley’s School of Criminology—Takagi was a rare individual who had both academic credentials and “field experience” in Criminology.

Over the following years, as professor and associate dean of the Criminology Department, Takagi helped transform Berkeley’s school into a center of the “crime and social justice” approach of Radical Criminology, which examined crime in the context of class and racial conflict. He helped found and edited the journal Social Justice.

In lectures nationwide and in his writings, which included the books Punishment and Penal Discipline (1980) and Crime and Social Justice (1981), both written with Tony Platt, Takagi examined the impact of racism and poverty on attitudes towards the law. He meanwhile made a name for himself as an advocate for prisoners’ rights and an influential critic of systemic police brutality.

Takagi and a colleague alienated then-California Governor Ronald Reagan and state authorities so deeply by their commitment to the rights of nonwhite communities that the School of Criminology was eliminated in 1974. Takagi then moved to Berkeley’s School of Education, where he remained for the rest of his teaching career.

Even as he worked in Criminology, Takagi branched out into other areas. In spring 1969, working together with students, he designed and led the experimental class Asian Studies 100x-Berkeley’s first-ever Asian American Studies class. While the university paid Takagi’s salary, he raised outside money for guest speakers, which he used to bring in community figures such as activist Karl Yoneda. Takagi also sponsored a lecture by Supreme Court resister Fred Korematsu (Korematsu, who was shy in those years about speaking publicly about his court case, apparently did not make a favorable impression on students).

According to Takagi, Emil Guzman, the son of a Philippine farm worker, arranged a get-together of students and farm workers at the United Farm Workers headquarters in Delano, where the group was welcomed by the famed labor activist Phillip Vera Cruz. Takagi subsequently published signal work in the area of comparative ethnic studies. Various of his students, including Ling-Chi Wang and Gregory Mark, went on to be distinguished teachers and scholars.

In connection with his Asian American Studies classes, Takagi encouraged students to reach out to local communities. He provided a strong model himself when he became centrally involved in the effort to save the bachelor hotels in San Francisco’s Little Manila. Takagi also was an outspoken supporter of the Black Panthers (whose first Minister of Information, Richard Aoki, was his student).

In 1971, Takagi announced support for a controversial referendum proposal to divide Berkeley into separate racial zones, so that white police—whom he charged had frequently used excessive force on African Americans—would no longer patrol black neighborhoods.

In 1975, when Wendy Yoshimura, a Japanese American associated with the Symbionese Liberation Army, was arrested (alongside fellow SLA member Patty Hearst) on charges of weapons possession, her bail was set at the astronomical figure of $500,000. Takagi befriended her family, and offered to serve as her sponsor so that she could be released from prison, which he considered essential for her legal defense. In the end, her bail was reduced on the condition that she live with the Takagi family at their Berkeley house, and she remained there throughout her trial (she was ultimately convicted and spent some three years in prison).

Takagi retired from teaching in 1989, four years after his wife’s death. On the occasion of his retirement, he received the signal honor of a tribute by Rep. Ronald Dellums, delivered on the floor of the House of Representatives.

In later years, he worked on various research projects, notably on the history of eugenics in early 20th century America. He enjoyed recognition for his contributions. For example, in 2007 he was honored by the National Council on Crime and Delinquency for his contributions to the field. He was also invited to speak that year at the Manzanar pilgrimage.

In 2008 the Association for Asian American Studies honored him with its Lifetime Achievement Award, and he made a sentimental return journey to Chicago to receive the award. His book Paul T. Takagi: Recollections and Writings, coauthored by Gregory Shank, appeared in 2012, three years before his death.

© 2019 Greg Robinson