“We all knew, we are going to go battle. And we expect to win. But we never knew what immediate death was like until we hit the frontline on the first day.”

— Lawson Sakai

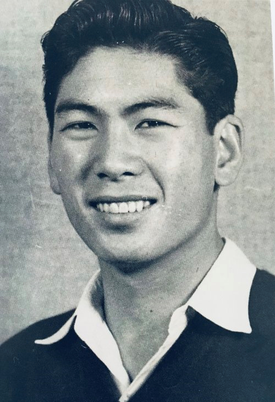

At a mere 21 years old in 1944, Lawson Sakai had seen and learned more about the stark realities of humanity, war, and loss than so many other people his age. After trying to enlist in the U.S. Navy in the wake of Pearl Harbor, he was denied the opportunity to serve his country due to the irrational, anti-Japanese fervor sweeping the West Coast. The Sakai family was lucky, however, in that they were welcomed and sponsored by the Seventh-day Adventist church in Delta, Colorado, avoiding the humiliations of incarceration. But when word got out that a segregated unit comprised entirely of young Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) was being formed in 1943, Lawson’s desire to serve outweighed the sting of forced removal and anti-Japanese sentiment. “I’m just a young kid, not in politics, all I know is this is my country,” he says.

And serve he did. As part of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Lawson experienced some of the most significant battles in Europe — and in all of military history — that brought the Nisei soldiers their deserved recognition and attention to their extraordinary synergy on the battlefield. But the price they paid was colossal and still leaves Lawson, now 96, with bouts of PTSD. “I drank a lot, but I think I was able to control it. It was the only cure that we had for PTSD. I still have it. And it will never go away.” To say he is owed our utmost gratitude feels like an understatement. To thank him for his service also falls short. But perhaps it is enough to call him precisely what he is — an American hero.

* * * * *

My name is Lawson Ichiro Sakai. I was born October 27, 1923 in a little place called Montebello in Southern California. It’s just seven miles from downtown Los Angeles.

Can you tell me what a typical day was like for you growing up in Los Angeles before the war?

Well, I’m a young Nisei. My parents were working, pretty much full time. So, I was just going to school and coming home, doing homework. And as I grew older, I began playing sports at high school. And I had a lot of other friends, so I was hanging out with classmates a lot. Had very little worries. Just kept growing up.

And what was the community like? Were there a lot of other Japanese Americans?

In our city of Montebello, I think I can count seven, maybe eight Japanese families. But we were kind of scattered. We were kind of in the western part of town and we had five acres of land, greenhouse. The other people were farming farther south, farther north. So the only time I would see these people would be at school. We didn’t have much of a community of Japanese. Most of our Japanese friends were in Los Angeles, and that’s because my parents were Seventh-day Adventists. And the church was in Boyle Heights. And it just so happened there was a German missionary that had been to Japan, spoke fluent Japanese. So, the Japanese Seventh-day Adventists people would go to that Seventh-Day Adventist church in the basement and he would preach to them in Japanese. So all these Issei, maybe there were 15-20 Issei. And this German man is speaking to them in Japanese. They had little Christian assemblies. So most of our friends were there. At least on my parents’ side.

And your parents were farming?

Well, we called it farming. The five acres there were a greenhouse. We grew Asparagus Plumosus Ferns. It’s a little green leaf that they put in bouquets and things. We also farmed about 13 miles away in a real remote farming area called Blue Hills. And it’s currently La Mirada Country Club. There were dirt roads. About seven Japanese farmers were farming out there. And there we grew mostly produce. My father planted about three or four acres of fig trees, so we had a fig orchard. We had seven to eight acres of flowering peaches which was in the spring, pinkish, white and red blossoms that he would cut and take to the flower market. And we grew other produce like beans. I can’t remember all the kind of produce we grew, but typical farming.

Right. So you were comfortable growing up?

This was during the Depression. Late ‘20s, early ‘30s. And nobody had money but the farmers had produce. We could eat pretty much what we grew and when they would go to the market and they would trade with each other and bring home things that we didn’t grow and so forth. So we always had a lot of vegetables to eat. And with rice and vegetables, and very little meat in those days. So Japanese food, you can pretty much [have] tofu, and that’s basically what we ate through the Depression years.

Can you tell me about the day Pearl Harbor happened? What do you remember about that day?

I can remember a lot because I was 18. I had graduated Montebello High School in 1941. So in September, I drove down to Compton Junior College and decided that’s where I was going to go. Well, Sunday morning, December 7th, I was doing my homework at home. I had the radio on and not paying much attention to anything and all of a sudden, when the announcer broke in and said Pearl Harbor has been bombed, it was kind of a stunning event.

I knew then what my parents had been talking about, among themselves basically, not to us, that there was a lot of tension between Japan and the United States because Japan had been forcing the invasion of China, Manchuria, Southeast Asia. And there had been many negotiations that did not work out. The United States had put an embargo on the oil that Japan had to get from Southeast Asia to supply their military. So when that embargo went in, they kind of put the choking effect on the Japanese military. My parents subscribed to the Rafu Shimpo, the Japanese newspaper, and we had a shortwave radio. A regular radio, with the shortwave tuning. And I think it was like two or three in the morning, they would try to tune in and catch something from Japan. And like most Japanese families, they would try to get some word from Japan.

Well, between the newspaper and the radio, all this friction was coming out and sure enough, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, it was war. And I didn’t know it then, but later as we discussed with Hawai’i boys, the United States government had been asked by Great Britain, to join the European war because Hitler had now conquered France. He was bombing Great Britain and next step was to invade Great Britain, and next step was to invade the United States. And the German Bund was very active on the East Coast of the United States, sending messages to the German submarines about the American ships going to Europe. I don’t know how many American ships were sunk off the eastern coast. So, Great Britain knew that the end was near if they didn’t get help.

Well, United States Congress in 1939 and ‘40, didn’t want to go to war because most of these Congressmen had been in World War I some twenty years before. Now their kids are 20, 21, 22, perfect age to go to war. They didn’t want to send their kids to war. So every time Roosevelt would say, “Let’s go help Britain.” “No.” So when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, FDR knew that if he declared war on Japan, he could also declare war on Germany. Exactly what happened. So immediately after Pearl Harbor, U.S. is engaging in war on two fronts. Even though the main enemy is Japan, most of the effort went to Europe.

And, in my case, I’m just a young kid, not in politics, all I know is this is my country. The following day, instead of going to school my classmates, three of them said, “Why don’t we go join the Navy?” [laughs] So we go to Long Beach. And Ed Hardage, Roy Kepner, Jimmy Keys, my Caucasian classmates, all accepted. And Sakai? “Wait a minute, you’re Japanese.” “I’m an American.” “You’re Japanese.” “You can’t go in the Navy.” Alright. I told my classmates, “They won’t let me join.” They said, “Well, the hell with the Navy! If you can’t go we’re not going either.” So we all left and went back to school. After that, I went back to Compton Junior College. Nothing happened. My classmates were great, they knew I was Japanese — they didn’t pick on me. They didn’t say anything about Pearl Harbor. I was playing football. The coach kind of picked on me a little bit. Coach Sagat he said, “You know, if Japan invades California, will you attack me?” [laughs] My football coach!

But anyway, Compton is near Long Beach and San Pedro and Terminal Island, and there were a lot of Japanese kids that were going to school from that area. All of a sudden, they weren’t there. And I didn’t know why. I didn’t know what had happened. I think it was a couple of weeks later before I found out. They had been forced to leave their homes on Terminal Island; the people in San Pedro were told they had to get ready to leave. Where they went I don’t know. I didn’t find out until much later that Terminal Island people had 48 hours to just pick up and leave. All of this was not publicized. Now we didn’t know. All we knew is what they told us. And the government told us very little.

Well, December 7th, I have to go back to this. My uncle and my aunt had come to the United States in 1895. They worked hard. They bought that five acre piece of property in Montebello under their name: Masajiro and Yarakai. Immigrants from Japan. But they bought it before the Alien Land Law was passed. So the government couldn’t take it away from them. And my aunt had divorced her husband, and so she retained the right to the property. She had papers, I guess.

So, going forward now. When we moved to Colorado, they were gone about three and a half years. I was still overseas in July of 1945 when they came back to California. My aunt, my parents entrusted the house and the glasshouse to this person in 1942. “We will be back in a month or two. Just keep track of it for us.” Well, after three and a half years, when they show up [the trustees] said, “Get out of here, it’s my property!” It took a little while, maybe a month or so, but they finally got him evicted. And they could move back in their own property.

They were lucky, then.

But even though they were aliens, they were able to hang on to that property. Another story, my wife’s side. In 1940, their father was getting wealthy. Biggest farmer in Gilroy. Well, he being an immigrant from Japan was unable to own the land but he had a benefactor who owned the place he was farming and wanted to give it to him. So basically he just handed it to him but legally changed the title to my father-in-law. For pennies probably. You know, very little money. This is about 1927 or ’28.

This man told my father, “You can’t own the land, but your children can.” At that point he had four children. She’s the second. So the four older, maybe they were fourteen, thirteen, twelve. You know, young teenagers. So they went to San Francisco and formed a trusteeship and there was a businessman in town that owned the International Harvester Tractor franchise. He was the trustee for the four little kids. So the kids, American citizens, owned the land which was actually owned by the father. That was close to a thousand acres. He owned it, they couldn’t take it away from him during the war. So very few Japanese families had that availability. Most of them leased the land and they lost it.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on April 23, 2019.

© 2019 Emiko Tsuchida