Returning to our questions about Eizo Yanagi, what kind of contacts did he actually have with African Americans in Chicago? Most of the following information on Yanagi can be found in his file at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington DC.1

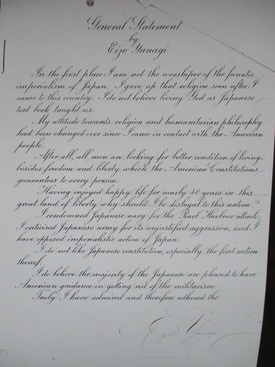

Eizo Yanagi

Eizo Yanagi worked as an engraving artist in pre-war Chicago and made his living by producing diplomas and certificates. He also had an English name, Frank Young (and at times went by Frank Eizo Yanagi). When the Japanese Prince and Princess Takamatsu visited Chicago in May 1931, Yanagi was a member of the committee that planned the reception for the royals, and was commissioned to make name cards for tables at a dinner party held at the Drake Hotel Golden Ballroom on May 13, 1931. He was called a genius,2 and his business and social status must have been well-established among Japanese in Chicago.

One source mentioned that Yanagi was also a photographer who made his living through wealthy clients. He was always seen walking around in Chicago with a camera around his neck, and his photography business invited his first arrest, just after the Pearl Harbor attack, on suspicion of being a military spy commissioned by the Japanese government.3

Yanagi was born in Kawanabe-mura in Kagoshima Prefecture, on November 20, 1891.4 After eight years of elementary school, he entered the United States as a young boy through Eagle Pass, Texas in 1907. He never returned to Japan. When later asked by an immigration officer why he came to the United States, Yanagi answered, “Since I was a child, I heard a lot of things about America, like that it’s a great rich country. I wanted to study in America, and become some kind of artist.”

Yanagi lived in southern California from 1907 to 1916, working on a strawberry farm near Los Angeles and waiting tables at hotels while taking a two-year high school correspondence course and attending the Coast College of Lettering. In the autumn of 1916, he moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he studied penmanship more seriously at the Zanerian College of Penmanship for four years, while supporting himself as a gardener. Yanagi was a good student.

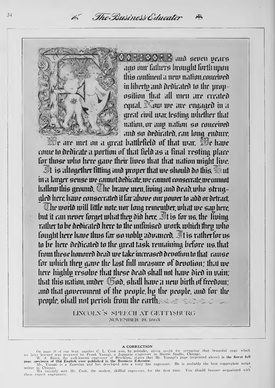

In an article in The Business Educator, W.A. Baird, the master engrosser and illuminator of Brooklyn NY, praised Yanagi’s engraving of Lincoln’s “The Gettysburg Address,” which appeared in that magazine’s September and October 1929 issues, as the finest specimen of Old English ever published in the magazine. Yanagi was introduced in the article as follows: “Mr. Yanagi is a Zanerian and has developed into a very fine engrosser. He is probably the best copperplate script writer in Chicago.”5

Yanagi had moved to Chicago in November of 1921. At first he worked as an engrosser at B.C. Kassell,6 a large engrossing and illumination company, where Baird was working. But after Baird left Kassell to open his own studio in the Wrigley Building, Yanagi also left Kassell and got a job as an engraver at the world’s largest department store, Marshall Field’s. But work at Marshall Field’s was not very interesting to him, so he did not stay too long, since there was a lot of work in Chicago. He was very ambitious. He took courses at the Art Institute of Chicago for two years, and was thinking of starting his own business in case he could not find a job in the engrossing circle in Chicago.7 He worked for Marshall Field’s for about 6 months, then found a job at another large firm, Harris Studio.8 He worked there for fourteen years, and in 1938, started his own business with Joseph M. Bruce at the Bruce and Young Studio.9

Although Yanagi worked in the Chicago Loop, he always lived on the city’s South Side, known as the Black Metropolis. From November 1921 to November 1938, he lived at the Japanese Young Men’s Christian Institute of Chicago (JYMCI) at 747 E. 36th Street. The JYMCI was a meeting place with lodging facilities for Japanese. During his residence at JYMCI, Yanagi was chosen to be one of its board members.10

From November 1938 to November 1940, Yanagi lived at 3850 S Ellis Avenue.11 From November 1940 to August 1941, he lived with an African American family at 4122 Indiana. From August 1941, until his first arrest, he shared quarters with another African American family, the Cullens, at 4243 St. Lawrence. When he was arrested for the second time, Yanagi was sharing an apartment with five African Americans at 420 East 42nd St. When asked by an immigration officer, “Why do you live with colored people?” Yanagi answered, “I opened that Negro district restaurant and I failed. Lost money. I was practically broke, so one of the colored fellows [sic]. He has a house over Indiana Ave, he used to come down my restaurant help cooking and waiting on table. Said I go his house and sleep [sic].”

On December 8, 1941, the FBI received an anonymous telephone call about Yanagi. The caller stated that Yanagi bragged that he had many times made men doctors overnight, that Japan had the strongest Navy, Army and Air Force and would be able to “lick the United States overnight”, and that he had worked all night for the Japanese Consul on confidential work. Morris L. Harris of the Harris Studio, a former employer of Yanagi, also testified against him. Harris said that Yanagi was in the office of the Japanese Consul, had refused Harris’s admission to the office because they were engaged in confidential work, and that the Consul was afraid that Harris and his colleague were spies for the US. According to Harris, Yanagi stole business from him while working for him, and that was the reason he had finally fired him. Clearly Harris had a grudge against Yanagi. When he was taken into custody on December 11, 1941, Yanagi stated that he had served in the United States Army during the last war. Though he had not seen any active duty, he stated, he had been in a training camp.

In a hearing conducted by the Alien Enemy Hearing Board of Chicago, no evidence could be found of Yanagi’s employment by the Japanese government or engagement in anti-American subversive activities. They believed that Yanagi was a sincere, frank, and harmless individual, subsisting on the very lowest fringes of Chicago society. The FBI searched Yanagi’s residence and office, but found no evidence to indicate that he was dangerous. One item discovered there was Yanagi’s camera, which he used to take pictures of African Americans on the South side, and approximately 1,000 small cards with the names of African Americans. Testifying that he had made the calling cards for African Americans, that the names on the cards were the names of his customers, and that he was pro-American, he was released on February 9, 1942.

However, in the summer of 1942, it was reported to the authorities that Yanagi was spreading Japanese propaganda and was dangerous. Even worse, he had not reported his change of address to the authorities, and the FBI could not find him at his registered address. Yanagi was arrested for a second time in October of 1942 on even deeper suspicions. Searches of his studio and his residence found, among others things, the following: a pamphlet titled “Three Million Negroes Thank the State of Virginia” which dealt with the aims of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Peace Movement of Ethiopia; a program for the “13th Annual Convention of the Moorish Science Temple of America,” held from September 15 to 20, 1940; an address book which featured the name of James Bey, possibly someone related to W. Harlan Bey, who was considered chairman of the Moorish Science Temple of America; an announcement of a meeting of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia, of which Madam Mittie Maude Lena (M.M.L.) Gordon was president; a copy of the magazine Friday, dated February 14, 1941, which carried an article entitled “Japanese Secret Drive Against America;” letters in Japanese; and war maps that had been published in newspapers.

Founded by the Black Nationalist Noble Drew Ali in New Jersey in 1913, the Moorish Science Temple of America was “the first mass religious movement in the history of Islam in America.”12 The Peace Movement of Ethiopia was a radical African American group in Chicago that insisted on the return of blacks to Ethiopia or Liberia. Primarily influenced by Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement (which by then, three years after Garvey’s death, was in decline), it engaged in anti-U.S. subversive activities such as sedition and draft dodging. Among the 85 arrests reported in the Chicago Defender on September 26, 1942 was M.M.L. Gordon, president of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia, and her husband, William, both of whom were arrested at 4451 South State Street.

The US Federal Bureau of Investigation had its own theories about blacks in Chicago during the war. According to the 1943 FBI Survey of Racial Conditions in the United States, in Chicago, the “uneducated Negro (is) stated to be deeply interested in fanatical or mystical organizations, … because of the fact that it gives the individual Negro some feeling of importance to be associated with a secret organization” and “that the attraction for the mystical or fanatical has existed for over a period of years.”13 Furthermore, “the attitude among the colored population in the Chicago area toward the war effort has been uncooperative” and “class consciousness has developed to the point where the Negro regards the war effort with but a lukewarm interest.”14

Although the investigations “failed to reveal pro-German and pro-Nazi activities among the Negroes” in Chicago, pro-Japanese sympathies could be found in several extremely radical groups in Chicago, such as the Moorish Science Temple of America, the Allah Temple of Islam, the Peace Movement of Ethiopia, The Colored American National Organization (The Washington Park Forum) and the Universal Negro Improvement Association.15 After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, M.M.L. Gordon of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia declared that “on December 7, 1941, one billion black people struck for freedom.”16 At weekly rallies in Chicago, she preached that “Negros should not take up arms against the Japs.”17 She also “claimed that her followers were citizens of Liberia, hence not subject to Selective Service.”18

Furthermore, in a search of Gordon’s effects, FBI found, among others, was “a memorandum in pencil longhand, consisting of four pages addressed ‘to His Highness General Sadao Araki’ War Office, Tokyo, Japan,” and several copies of letters typewritten and in pencil longhand, addressed to the honorable Kenji Nakauchi. One of these letters dated May 22, 1934, consisted of two pages, and was from Mrs. M.M.L. Gordon, “seeking his cooperation and advice.”19 There was also a “Return receipt for registered article, addressed to Mrs. M.M.L. Gordon from Hiroshi Saito and card from registry Division regarding same package, dated October 16, 1937.”20 The registered article delivered to Saito was assumed to be the Araki letter written by Gordon.21 However, the FBI reported that the content of this registered article was unknown.22

The letter to Araki, according to the FBI report, “petitioned that in the event of war between the United States and Japan the members of the Movement be advised as to their conduct as they are not enemies of the Japanese and were hopeful of uniting the dark races of the world. It also asked for a truce between them and the “dark skinned people of the eastern world.” The report noted that the letter “concluded with the statement that they (the blacks) will not fight against “our dark skinned brothers of the eastern world” and expressed their desire to enter into a secret alliance with the Japanese government.”23

Kenji Nakauchi was the acting consul of Japan in Chicago from May 1934 to June 1935, and became the first honorary president of the Mutual Aid Society,24 which was started by Japanese in Chicago in January 1935, with Nakauchi’s approval.25 Hiroshi Saito was the Japanese ambassador to the United States from 1934 to 1939. Beginning in 1934, Saito visited Chicago several times in order to attend events such as the World’s Fair: A Century of Progress.26 Saito had a close relationship with the Mutual Aid Society, as evidenced by the fact that he wrote the epitaph for a mausoleum for Japanese in Montrose Cemetery in July 1937.27

Gordon was tried for sedition on February 1, 1943. The documents seized from Gordon, which included names of Japanese diplomats, seemed to indicate her connection with Japanese government. An informant testified that Gordon was the recipient of Japanese money given to the leader of the Moorish Science Temple of America,28 but she denied having received the money and said that she neither wrote nor edited the letter to Sadao Araki.29

In response to questions about the documents and his connection with these groups, Yanagi admitted that he had business with Gordon of the Peace movement of Ethiopia and Moorish Science Temple of America. He stated that “during a visit of … a prince of Nigeria, who visited Chicago in March 1941, he was called upon by the Peace Movement of Ethiopia through Madam Gordon to photograph the group, that while he is not a professional photographer he has done a great deal of photographic work in the negro section of Chicago, and due to his expert penmanship has also written many letters and prepared fancy cards for the negroes; by that reason he is well known to them.”

Yanagi testified that “he first met Gordon when the prince came to visit him in his studio,” and that “Gordon gave him some of the propaganda material found among his possessions to read.” Yanagi emphasized that “his connection with Gordon and other negroes in these negro movements was only for business purpose” and further stated that he had no interest in the negro race; that in fact he disliked them because they didn’t pay for his photography and penmanship work.

Most likely in order to impress the investigators about his involvement with American people and society, Yanagi mentioned that “he knew several second generation Japanese who are presently in the United States Army, and that he has been in correspondence with one” and expressed his wishes “to remain here and does not believe in the divinity of the Emperor.” The Alien Enemy Hearing Board, nevertheless, did not change their opinion that “Yanagi could be engaged in disseminating subversive propaganda among the negroes and that he was a dangerous alien and recommended internment.”

Although Yanagi was unable to avoid incarceration, a camp report on Yanagi offers another perspective on Yanagi’s tenacious survival strategy, one that is interesting to Issei immigrants, like the author of this piece, who are culturally and linguistically handicapped in English-speaking society. While “United States Attorney in transmitting a transcript of the rehearing state[d] that it is of little value because subject uses poor English and is difficult to understand, and the reporter had great difficulty in taking down the majority of the testimony,” a camp report dated June 6, 1944, from Kooskia, Idaho stated that “Yanagi speaks and writes very good English and helps a great many of the other internees in their study of the English language.” Yanagi had been very young, between 14 and 17 years old, when he came to America, so he must have naturally acquired almost native fluency in English, at the very least speaking with less of an accent, -yet the report said that his accent made his testimony unsatisfactory. Was Yanagi really such a poor English speaker, or were the hearing board members informed by racial hostility, or did he act the part, in order to suggest his innocence?

After he was released from incarceration on March 11, 1946, Yanagi returned to Chicago and married Fumi S. in Chicago on February 9, 1949. Fumi was a Nisei who was born in 1915 in the state of Washington. In July 1942, she and her family, were imprisoned at the Tule Lake concentration camp in California, but Fumi found domestic work in Illinois and moved to Chicago with her sisters in December 1942. She registered for the Women’s Army Corps in January 1944.

We know little about Yanagi’s new life with Fumi in Chicago, except that he lived at 731 North Clark street in 1949 and 1950.30 He died in Chicago on October 17, 1966. The story of his more than 40 years as a Japanese Chicagoan was one of the most dramatic in Japanese Chicago history.

Notes:

1. General Records of the Department of Justice WWII Alien Enemy Internment Case Files 1941-1951, Record Group Number RG 60, Box 255

2. Nichibei Jiho, May 13, 1931

3. Kazuo Itoh, Chicago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 302

4. US World War II Draft Registration Card. Some documents recorded 1890 and 1893

5. The Business Educator, October 1929

6. 105 N Clark (1923 Chicago City directory)

7. Yanagi’s letter to E.A.Lupfer, November 29, 1924, The Zanerian College Collection

8. 140 South Dearborn, (1923 Chicago City directory)

9. 417 South Dearborn, later 20 West Jackson Blvd, not in the city directories

10. Correspondence from JYMCI to W. J. Parker, April 2, 1929, YMCA collection, Japanese department, Box 103, Folder 1, Chicago History Museum

11. Chicago Telephone Directory March 1938-September 1939

12. Nathaniel Deutsch, “The Asiatic Black Man”: An African American Orientalism?” Journal of Asian American Studies, Volume 4, Number 3, 2001, page 196

13. Robert A Hill, The FBI’s RACON: Racial Conditions in the United States During World War II, page 91

14. Ibid, page 91-92

15. Ibid, pages 91-94

16. Ernest Allen, Jr. “Satokata Takahashi and the Flowering of Black Messianic Nationalism”, The Black Scholar, Winter 1994, page 25

17. Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan 27, 1943

18. Time Magazine, October 5, 1942

19. Robert A Hill, The FBI’s RACON: Racial Conditions in the United States During World War II, page 527-528

20. US District Court/Northern District Illinois CR 33709 Box 1155, National Archives and Registration Administration, Chicago.

21. Chicago Daily Tribune, Jan 29, 1943

22. Robert A Hill, The FBI’s RACON: Racial Conditions in the United States During World War II, page 528

23. Ibid, page 527

24. Nichibei Jiho February 9, 1935, Executive Secretary’s notes 1935-1941, Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago

25. Executive Secretary’s notes 1935-1941, Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago

26. Chicago Daily Tribune, May 20 & 23, June 26, 1934

27. Itoh Kazuo, Chicago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, Page 258

28. Chicago Daily Tribune, January 28, 1943

29. Chicago Daily Tribune, Febuary 2, 1943

30. Chicago Japanese American Yearbook 1949, 1950, Legacy Center at Japanese American Service Committee in Chicago.

© 2019 Takako Day