Colonization to Chiapas, Mexico

Even after leaving the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Enomoto Takeaki continued to pursue his dream of overseas colonization. In 1893, he founded the Colonization Association and launched a project to send colonists overseas.

They set their sights on Mexico, which had already concluded a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with Japan in 1888 and opened the first consulate in Latin America in 1891. At the time, Mexico was ruled by Porfirio Diaz, who had been in power for 35 years since coming to power in a coup d'état in 1876. To develop the country, they actively brought in foreign capital, modernized industry, and invited immigrants. When the Japanese government had conducted an investigation, a report had already been published indicating that agriculture could bring great profits.

For this reason, the association sent its secretary, Nemoto Sho 1 , to Mexico, Brazil, India, and other countries between July 1894 and March 1895, to carry out a business inspection tour. Around the same time, they also sent Hashiguchi Bunzo 2 , who had just returned from studying in the United States, to the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico to conduct a survey. Hashiguchi reported that Escuintla was the perfect place for settlement, and that it was land suitable for coffee cultivation. Nemoto made a similar report.

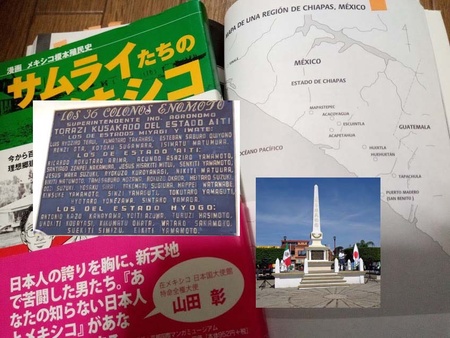

Upon hearing this report, Enomoto established the Japan-Mexico Colonization Company at the end of 1896 to raise funds. Although they only managed to raise about 100,000 yen, half of the amount they had initially planned, they sent out a colonization group of 36 people from Yokohama on March 24, 1897. The group arrived in Escuintla on May 19, but malaria was rampant and the rainy season meant that they could not cut down trees in the jungle. The coffee seedlings that were expected to be a source of income did not suit the local environment, and the settlement itself was not suitable for coffee cultivation, so they did not grow well, forcing the colonization group into a difficult situation. As a result, some people fled after just a few months, and the shortage of funds was never resolved.

In 1900, Enomoto transferred the business to Fujino Tatsujiro, a member of the Colonization Association and a member of parliament, and effectively withdrew from the Mexican colony. Fujino continued Enomoto's business, but in 1901, despite prior investigations by Nemoto and Hashiguchi, the colony collapsed. Terui Ryojiro, who later became the representative of the Japan-Mexico Cooperative Company, explained the failure of the Enomoto Colonization Corps as follows: "They had no intention of running a colonization business seriously, but simply intended to send immigrants and make a profit from coffee cultivation, which was considered the most profitable crop at the time. Therefore, when purchasing land, they bought mountainous areas that were unsuitable for colonization, and they obtained the support of shareholders by promising profits from coffee, which was Viscount Enomoto's mistake in the first place." 3

Japan-Mexico Collaborative Company and the Mexican Revolution

After the Enomoto Colony was dissolved, the remaining six immigrants established the San'ou Cooperative Association in the neighboring town of Acacoyagua in 1901, which was a socialist association that did not recognize private property. The association then expanded its business as a Japan-Mexico Cooperative Company, and by 1912 had grown to become the largest overseas business operated by Japanese people. The company also focused on educating children, and established the first Japanese school in the Americas. In 1902, Tsunematsu Fuse and his wife, Nonchurch Christians, arrived and educated second generation Japanese and Mexicans. They also made a great contribution to the local community by compiling a Spanish-Japanese dictionary, laying waterworks and building bridges.

However, this Japan-Mexico Collaborative Company was dissolved in 1920. It is said that the reasons for this were internal disagreements and excessive business expansion, but it is also true that the company suffered great economic damage due to the turmoil caused by the Mexican Revolution.

At that time, Mexico had a dictatorship under President Porfirio Diaz, who aimed for modernization. At the end of his administration, 98% of the railroads, 97% of the oil and mining resources, and 25% of the land were controlled by foreign capital, and American companies owned a large part of the fertile farmland. Although industry was modernizing, the working conditions of workers deteriorated, and although exports of agricultural products increased, the lives of small farmers were very difficult (97% of farmers were landless tenant farmers). The production of necessities was low, and most had to be imported. In addition, because the military was the support base, political party activities were restricted, and even the Catholic Church was under surveillance. As a result, rebellions aimed at overthrowing the Diaz dictatorship, known as the Mexican Revolution, spread throughout the country, and President Diaz was eventually exiled in 1911. After that, the civil war aimed at democratization, land reform, and economic reform in Mexico continued for a long time, until the new constitution was enacted in 1917.

The future President Obregon promised to pay compensation to the foreigners who suffered great damages from the revolution, but the Japanese in Chiapas notified them that they would waive that right. As a result, the president and many other cabinet members and state government officials gained a new appreciation for the Japanese, and they gained even more respect. Furthermore, during the war, 73 Japanese families living in Chiapas were exempt from forced relocation to the capital and other areas.

The Japanese immigrants in Chiapas fought hard in these times, established their position in Mexican society, and won trust. It is because of their contributions that the name of Enomoto Colonization remains in Mexico today.

The personality of Enomoto Takeaki

Enomoto had long believed that overseas colonization was necessary to make up for Japan's population situation and lack of resources, and considered not only Mexico but also Asia and Oceania to be important colonial destinations. Although the Chiapas colony ended in failure, in line with Enomoto's vision and the country's political and economic strategies, large-scale colonization projects were subsequently carried out, particularly in Asian countries. Overseas migration, which was incorporated into imperialism, was also encouraged, but most of the Japanese who applied may have simply been seeking larger land and wealth.

Those who were close to Enomoto said that he was a man of great loyalty, quick to cry, who readily lent money, and who trusted people easily. In his later years, he lived in a mansion in Mukojima and often took walks in his favorite Mukojima Hyakkaen Gardens. He was a heavy drinker and referred to sake as "rice water."

After his pardon, he served the new government despite being a former Shogunate retainer, and was viewed with considerable criticism by the former retainers, but it is said that he was intent on helping former retainers and their families throughout his life. The development of Hokkaido and overseas colonization may have been aimed at improving the lives of former retainers and providing new frontiers.

In 1905, after the Russo-Japanese War ended with a Japanese victory, Enomoto retired as a vice admiral and died on October 26, 1908, at the age of 73. He was given a naval funeral and buried at Kichijoji in Bunkyo Ward, Tokyo. Enomoto's eldest son, Takenori, married Kuroda Kiyotaka's eldest daughter, Umeko, and inherited his father's viscount title and became a member of the House of Peers. His great-grandson, Takamitsu Enomoto (born 1935), a visiting professor at Tokyo University of Agriculture, is still alive (it is unclear whether he is currently a visiting professor), and Professor Enomoto has a daughter, Fujiko, and a son, Ryuichiro.

Notes:

1. Tadashi Nemoto was a former samurai of the Mito domain. He graduated from the University of Vermont in the United States in 1889 and later became a member of the House of Representatives.

2. Hashiguchi entered Keio University in 1872, then worked for the Hokkaido Development Commission, and in 1879 studied at Massachusetts Agricultural College as a government-sponsored student. After returning to Japan, he worked for the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce. He also served as a councilor for the Hokkaido Prefectural Government and the principal of Sapporo Agricultural College. After a visit to Mexico, he joined the Taiwan Governor's Office's Industrial Bureau, and in 1896 he became the governor of Taipei County.

3. " The Mexican Enomoto Colony: The Life of Ryojiro Terui: The Reality of the Colony's Collapse: Former JICA Branch Director Publishes Book " (Nikkei Shimbun, December 2, 2003)

© 2019 Alberto J. Matsumoto