The Nikkei, however, were not the first Asia Pacific Americans to serve in America’s wars. Filipinos served in the War of 1812 and Filipino, Chinese, and nationals of various southeast and south Asia nations served in the Union and Confederate armies in the Civil War.

From their settlement in the Mississippi delta region of southeast Louisiana, Filipinos served in the army of Jean Baptiste Lafitte and MG Andrew Jackson to defeat the British in Louisiana in 1815. These Filipinos, who had served on the crews of Spanish galleons transporting goods from Manila and Acapulco, jumped ship at New Orleans beginning in 1763. And in 1587, twenty years before Jamestown, Virginia, was settled and 189 years before the US was founded, Filipinos had arrived in Morro Bay, California, located midway between San Jose and Los Angeles.

The first Chinese arrived in the US in 1815 to work on the transcontinental railroad and by the time of the Civil War there were about two hundred living in the eastern US, some working in the cotton fields. About sixty Chinese men served in the Union and Confederate forces in the Civil War and three held corporal ranks commanding white troops.

Documented Nisei military service in the US began with Nobuteru Harry Sumida who was born in New York City on December 25, 1871. Ansel Adams’s book, Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans, as well as other sources, reports that Sumida was raised by Caucasian foster parents soon after he was born and never knew his birth parents. Educated at New York City public schools, Sumida graduated from a Manhattan high school. He learned Japanese through self-study; he ordered books from Japan and gained proficiency in Japanese literature. He also worked on a sailing ship, which visited Kobe, Japan, but he did not go ashore.

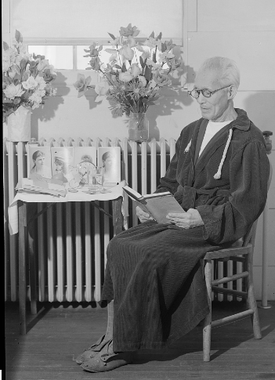

In 1891 Sumida enlisted in the US Navy and was assigned as a gunner on the USS Indiana. During the 1898 Spanish American War battle in Santiago Bay, Cuba, he received shrapnel wounds in his leg that disabled him permanently and for which he received a monthly government compensation. At the time of his discharge in 1899, his rank was Seaman First Class. In 1904, at age 32, Sumida married Johanna Schmidt in NY. Ansel Adams’s book noted Johanna died in 1941 and that they had no children. When WW II began, Sumida lived in Temple Sanitarium in Los Angeles. In the 1942 mass evacuation, Sumida was placed in the Manzanar Internment Camp Hospital because of rheumatism in his leg caused by the war wound. In time he was transferred to the Manzanar senior center.

In addition to Seaman First Class Sumida, eight Japanese nationals served as US Navy seaman in the Spanish American War of 1898. The eight Japanese nationals were among the two hundred sixty seamen who perished when the USS Maine sank in the Havana, Cuba, harbor as the result of an explosion. Some seamen’s bodies and remains were eventually recovered with ten declared missing. The names of the dead USS Maine seamen including the eight Japanese nationals are inscribed on the USS Maine Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery. The Japanese nationals who sank with the USS Maine are also listed on the Japanese American War Memorial Court in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, the only location where ethnic Japanese killed in combat in all wars are memorialized.

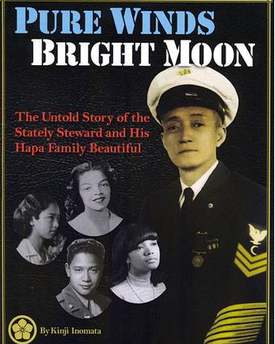

Also during the Spanish American War of 1898, Japanese nationals Kenji Inomata and his friend, speaking very little English, arrived in New York City as stowaways – jumping overboard and swimming ashore as their ship approached New York harbor. According to the book Pure Winds Bright Moon by Kenji’s grandson, Kinji Inomata, as well as other sources, in 1906 Inomata enlisted in the US Navy as a Third Class Mess Attendant. He traveled the world with the Navy, earning promotions and eventually serving as Steward to captains and commanders who commended him for trust and integrity. After 30 years of service, Inomata retired as Petty Officer First Class and lived in Los Angeles, CA. He also became a naturalized US citizen. However, the date of naturalization is not available. In 1918, he married Genevieve Beckham, who was of Caucasian and African heritage. Following his military service, in 1937, Inomata worked for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. When WW II broke out, Kenji Inomata was exempted from the mass internment and allowed to live a normal life in the home he bought in Los Angeles, although it is not known if he held his job at the LA Department of Water and Power during the war. The Inomata family military service continued as Kenji and Genevieve’s son, Takeo, served in the 442nd RCT.

When the US entered WWI on April 5, 1917 an announcement in English, Chinese, Japanese and Korean urged “nationals of Allied countries” to enlist in the Hawaii National Guard as “this would help you obtain US citizenship.” However, the examiner for US Naturalization Service amended the statement; instead, he said “oriental veterans” were not eligible for naturalization, only the “white race” or “African race” were eligible. Nevertheless, a large number of Japanese nationals applied to the Hawaii National Guard. Due to the large number, the Japanese nationals were placed in a separate unit, Company D, with a Japanese national as commander. All written and oral communication were in Japanese. After the war, on November 14, 1919, US Judge Horace Vaughn allowed 400 Japanese national soldiers to be naturalized. Yet when Judge Vaughn’s term ended six years later the territorial government voided his decision.

The long and arduous road for ethnic Japanese and other Asian immigrants to gain naturalized US citizenship came to an end in 1952 with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act which allowed Asian immigrants to become US citizens.

[The JAVA Research Team thanks AARP (Ron Mori and Ryan Letada); NPS Manzanar Historic Site (Alisa Lynch); Pacific Citizen (Susan Yokoyama); Libraryof Congress (William Elsbury); Densho (Tom Okino); and MG Taguba, USA (Ret) for their support.]

*This article was originally published in JAVA e-Advocate on July 7, 2019.

© 2019 JAVA Research Team