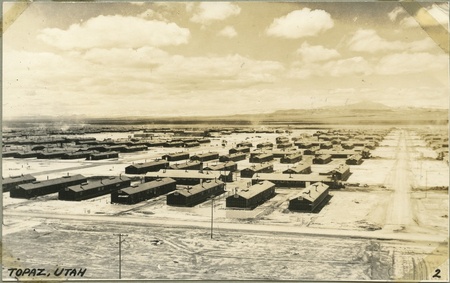

The “Central Utah Relocation Center”—more popularly known as Topaz—was located at a dusty site in the Sevier Desert and had one of the most urban and most homogeneous populations of the camps, with nearly its entire inmate population coming from the San Francisco Bay Area. Topaz is perhaps best known as the site of the fatal shooting of an inmate by an overzealous camp sentry in April 1943 and for its art school, which included a faculty roster of notable Issei and Nisei artists. It was also the site of significant protest against the “loyalty questionnaire” in the spring of 1943 and of a variety of labor disputes.

The second least populous of the War Relocation Authority camps (to Amache), Topaz had a peak population of 8,130 inmates. The Topaz Museum, which opened to the public in 2015, is located in nearby Delta, Utah and today owns much of the land on which the camp was once built.

Here are ten little-known stories from Topaz concentration camp:

“SWIRLING MASSES OF SAND IN THE AIR”

While dust storms took place at many of the WRA camps and are part of the standard narrative about these sites, they seemed to be particularly bad at Topaz even by WRA standards. Tony O’Brien, the acting project attorney, wrote in a November 1942 memo that the “dust storms are much worse than those encountered at Minidoka. The dust is more powdery in texture and penetrates every crevice on the project,” he wrote.

Maxim Shapiro, a visitor to the camp, wrote of the dust in December 1942 that “no one who has not seen it can imagine its ill effects. It penetrates everything—it fills your mouth, nostrils, the pores of your skin, your clothing—and all efforts to keep yourself or your room clean are just futile efforts…”

“We could barely see one inch ahead of us,” wrote Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) fieldworker Doris Hayashi of a dust storm in November 1942. “It swept around us in great thrusting gusts, flinging swirling masses of sand in the air and engulfing us in a thick cloud…,” wrote Yoshiko Uchida in her memoir.

THE OFFAL WAS AWFUL

In the spring and summer of 1943, the camp was unable to purchase sufficient meat due to outside shortages, and began serving a succession of organ meats—livers, hearts, tripe, etc.—that most inmates found unpalatable. Widespread complaints followed, including appeals to the Spanish Consul and the State Department, and calls for the firing of the chief steward. The situation was eventually resolved when the camp farming operation began to deliver beef and pork to mess halls in August 1943.

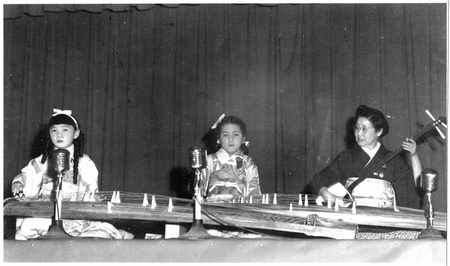

THE TOPAZ MUSIC SCHOOL

While the Topaz Art School is relatively well-known, the equally notable Topaz Music School is much less well documented. “It is very strange because a lot of people didn’t know that there was a music studio except the people who actually went there, and even some of those people can’t remember the details about it,” recalled Kazuko Iwahashi in a 2011 Densho interview.

As with the art school, the impetus for its creation came from the relatively large number of artists/musicians among Topaz’s urban population. First organized in the Block 35 Recreation Hall, it later moved to Barrack 6 of Block 1. Teachers and students and their families spent ten days putting up walls, ceilings, and sheet rock prior to the November 1 school opening. The school offered courses in piano, vocal, violin, solfeggio, harmony, history of music, choir, ensemble, orchestra, and noh drama. The peak enrollment at the school was 653, ranging from four-year-olds to a seventy year old choral student. The school put on regular recital programs featuring the students.

As with other education endeavors, supplies and equipment were an issue. In particular, there was the matter of pianos. Though the school had access to seven pianos—many came from individual inmates and Japanese American churches in the Bay Area—this was not sufficient, and piano students were limited to mere minutes of weekly practice time. Violin students had to provide their own instruments. Nonetheless, the music school and its various performance programs provided a welcome diversion for students, teachers, and the community alike.

THE SANTA ANITANS

Concentration camp life created some unusual groupings, alliances, and, sometimes, out groups. One of the oddest instances of the last was the fate of Santa Anitans at Topaz. Essentially the entire population of Topaz came from the San Francisco Bay Area, and nearly all came through the Tanforan Assembly Center. But one of the first groups to be removed from San Francisco in April 1942 was sent to Santa Anita instead, since Tanforan had still not been completed. This group spent nearly six months at Santa Anita and was among the last to arrive at Topaz on October 7. Even though this group shared common Bay Area roots with the rest of the Topaz population, it seems their time at Santa Anita had changed them.

Their long incarceration at Santa Anita along with the miserable conditions they faced as late arrivals at Topaz led to their being viewed by other inmates as having “a cocky attitude” and having “a chip on their shoulder.” Community Services Chief Lorne Bell described them as “something of a problem, reflecting to some degree the very unfortunate conditions which must have prevailed at that center [Santa Anita].” Their incarceration with Los Angeles people also seemed to have changed them in the view of the Bay Area people. Fred Hoshiyama, who was working as a JERS field worker, described their arrival with some degree of bewilderment:

Many of the young nisei boys who were conservative dressers came off of the bus in “zute (sic) suits” and other flashy dress wear. The girls wore their hair in styles different from the Tanforan group ala Hollywood glamour styles—either long like Veronica Lake or short and put up. Their language, their attitudes, their mannerism changed to the extent that It was easily discernible and many of the Tanforan girls and boys expressed surprise as well.

The Santa Anita group was housed in Blocks 33, 34, and 40 and apparently remained somewhat distinct from the rest of the population.

THE HAWAIʻI GROUP

Topaz was one of two WRA camps to have a sizable contingent who had been shipped from Hawaiʻi. (Jerome was the other.) The group of 226 arrived in March of 1943 and were housed in Block 1. Most—176—were single men, most of them Kibei. Inmates and WRA staff went through great efforts to welcome them upon their arrival. Many had been interned at Sand Island previously or were family members of such internees. Most of them eventually ended up going to Tule Lake after segregation and many went on to Japan.

*This article was originally published on the Densho Blog on September 11, 2019.

© 2019 Brian Niiya