My recent article on the French-born mixed-race Japanese writer Kikou Yamata, whose works were published in translation in the United States and discussed in Nisei literary reviews, has inspired me to delve more into the fascinating and varied history of the connections that Japanese Americans forged with France during the period before and after World War II, and the nature of their cultural exchange.

This is an enormous subject, which encompasses such diverse elements as the experience of the Nisei visitors, students and creative artists who went to Paris and outside, including their interactions with Nikkei from around the world, (There are other elements as well, such as the visits of French authors to North America and their studies of Japanese communities, that I don’t have room to address here). My goal here is to scratch a little of the surface of the question, then leave the question for abler hands to develop more fully.

In the years after World War I, a galaxy of Nisei creative artists took up residence in France. Soprano Agnes Yoshiko Miyakawa, a native of Sacramento, studied voice in Paris, and then made her starring debut at the Opéra-Comique in Paris as Ciao-Ciao-San in Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly in 1931, winning critical and popular acclaim.

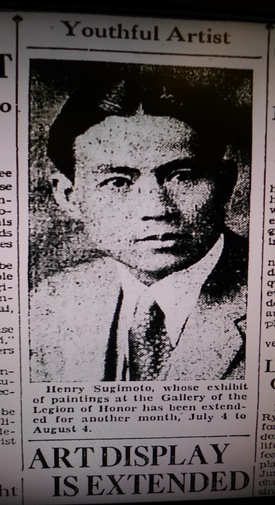

Painter Henry Sugimoto arrived in France in 1928 and ended up living there for three years, during which time he became close to a circle of Japanese artists. While he initially took up painting studies at the Académie Colarossi in Paris, after one of his paintings was rejected for inclusion by the prestigious Salon d’Automne, he left the Académie and took up residence in the French countryside. One of his landscape paintings was ultimately accepted for the 1931 Salon d’Automne.

Sculptor Isamu Noguchi likewise arrived in Paris in the 1920s, and studied with the famed sculptor Constantin Brancusi. Frances Fitzpatrick Osato, a white woman from Chicago who married the photographer Shoji Osato, took their three Hapa children for an extended stay in France in the late 1920s. The eldest child, dancer Sono Osato, was recruited while in France to dance with the Ballets Russes. The youngest child, Timothy Osato, had his portrait sketched by the famed postimpressionist painter Léonard Foujita (AKA Tsuguharu Fujita).

Surely the most eminent Nikkei expatriate from America was the actor Sessue Hayakawa, who was based in Paris during most of the 1930s and the war. When he made a French film about Japan, Yoshiwara, which was set in the red-light district of Tokyo, it aroused an opposition within Nikkei circles parallel to that caused by his role in the 1915 silent Hollywood film The Cheat. The film was officially banned in Japan.

Once war in Europe was declared in September 1939, there was an exodus of Nikkei to the United States. According to one article, a group of 180 Japanese refugees from Europe set sail for home on a Japanese ship, which first docked in New York. Among the passengers were 25 distinguished Japanese artists, led by the painter Minoru Okada, who brought back with them the hundreds of artworks they had produced during their years working in Europe.

Meanwhile, a number of Nisei who had been working in Europe also rushed to return home. Miné Okubo, who had been travelling through Europe on a Bertha Taussig fellowship, later claimed that she had sailed on the last boat leaving the Continent.

Newton Tani, who had moved from San Francisco to Paris to study piano during the 1930s, managed to find his way back to the United States—he would be later confined at Topaz as a result of Executive Order 9066, and served during World War II as Director of the Topaz Music School.

Another musician who would ultimately be confined at Topaz was the violinist Masao Yoshida. Yoshida, born in Japan, had come to the United States as a baby and grew up in Alameda. He spent several years in San Francisco in the 1930s studying with Naoum Blinder, concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony, before undertaking further study and scheduling performances in Belgium and France. Caught in Paris at the start of war, he sold his books for food and borrowed money so that he could flee, first to Belgium and then across the English Channel, and finally to the United States.

Shizuo Kato, a Vancouver-born painter who spent the prewar years studying in Paris, was also able to leave Europe on a Japanese ship, the Kashima Maru, and return to the West Coast.

Not all the refugees stuck in war-torn France were able to get out. Dr. Kenzo Shinohara, who graduated from the College of Medicine of the University of Paris in the late 1930s, was shocked by the coming of war. While en route towards Warsaw in summer 1939, he received a summons to the Lille University Hospital urging him to come replace French doctors who had been conscripted for work with the Red Cross. Both Shinohara and his sister-in-law Atsuko Kiyoda—a graduate of L.A. High School who had moved to Paris to study millinery design—found themselves unable to get back to Los Angeles. Kiyoda, for her part, married a Jewish Hungarian named George Szekeres and lived with him in Paris under the German occupation. (The couple fled to Hungary in 1943, but George was subsequently arrested as a Jew, sent to forced labor in Russia, and ultimately arrested by the Gestapo—Atsuko finally located her husband in a Displaced Persons camp in Germany at the end of the War). Atsuko Kiyota Szekeres ended up emigrating to Rio de Janeiro in 1956—by which time she was listed as single.

In the years after World War II, a number of Nisei, notably former GIs, took up residence in Paris. Shinkichi Tajiri and Steve Shigeo Wada each used the GI Bill to travel to France and study art with French masters. John Yoshinaga moved to France and took classes in French civilization. Robert Chino, a 442nd veteran, decided to re-enlist after the war and stay in France and Italy rather than return to Chicago. In the late 1940s, Hiroshi Tamura was awarded a two-year fellowship in Paris by the Art Institute of Chicago. Hawai‘i-born Dorothy Furuya studied for three years at L’Académie Julien in Paris.

In 1950 painter Ellen Ochi, a graduate of the Cleveland School of Arts, won a $1000 Page scholarship to study in Paris. 442nd veteran Wilson Makabe and Mary Lou Kawasaki were sponsored by Temple University to study at la Sorbonne in 1952. In early 1954, the Hawaii-born anthropologist Dr. Hiroshi Daifuku was appointed as a program specialist in the Museums and Monuments Division of the Departent of Cultural Affars at UNESCO. He would remain in Paris with his family until his retirement in 1980.

One particularly intriguing postwar story is that of Lilli-Anne (AKA Lillian) Oka. Oka, a West Coast Nisei whose family had transplanted to Chicago, was invited by the Marquis de Cuevas to join the Ballet de Monte Carlo in 1949, and she was one of the stars of the troupe’s Paris season that year. She subsequently married singer Andre Tcherkassky, returned to the United States, and opened a ballet studio in Kensington, MD, where she trained numerous dancers—most notably her daughter Marianna Tcherkassky, who spent a long career as a principal dancer with American Ballet Theater. So if it is true, as Oscar Wilde famously observed, that when good Americans die they go to Paris, according to Oscar Wilde’s famous sally, then the City of Light can be said to house the spirits of countless Nisei!

© 2019 Greg Robinson