Japanese culture is present in Peru in an evident and unmistakable way, especially when it is exhibited in formats with all the Japanese iconography or when it is carried out by the Nikkei community and its cultural dissemination spaces. For this reason, origami is a 'rara avis', a manual and artistic practice that has made a different place for itself and that continues to mutate to reach new audiences.

But let's start with a fundamental question: did the art of paper folding, origami, emerge in Japan?

History says that it actually originated in China, where it had a more practical than artistic purpose, but that it was in Japan where it acquired the status of a creative craft. Marta Silva de Tagata is a Colombian student of origami, which she spreads through the Origami Peru Educational Association. She says that this art spread in Spain, where it is called origami, the folding of paper into figure shapes.

“In China, paper folding was used to wrap products, not to make figures. It is with the invention of the printing press that this art can spread,” says Marta.

Although there are very ancient indications in Japan, it was its religious ceremonial use, as an offering or in Shinto weddings, that made it popular, spreading around the world at the time of Japanese migration, thanks to the use of an accessible material: paper. . The father of modern origami, Akira Yoshizawa, established a series of procedures in the 1950s that are still practiced and taught today.

“Some principles and terms were established for its teaching,” says Marta, who says that at first origami was made only with a square sheet of paper that only had to be folded. Later, kirigami appeared, in which it is cut, the use of glue to create other shapes and additional decorations (painted, elements of another material, etc.) that have given it new artistic airs.

origami Peru

In Peru there is no agreed date to talk about the appearance of origami, but it is known that many Japanese migrants practiced it in their family environment, such as the father of the poet José Watanabe, the painter Harumi Watanabe, and when he was a child, the painter Venancio Shinki was entertained with this craft. More recently, the art of paper folding invaded the creations of artist Carlos Runcie Tanaka, who made origami crabs in his installations.

On the other hand, the introduction of books to learn origami and the pedagogical value that has been attributed to it since the German Friedrich Fröbel, creator of the kindergarten, the so-called kindergarten, incorporated it as a teaching technique, has influenced schools, centers cultural and other educational spaces make use of it. The Peruvian Japanese Cultural Center must be one of the first to include a special origami course.

Fine Arts professor Narciso Ezequiel Sánchez was in charge of teaching it in 1972 and was later followed by his wife, Angélica Molina, who has been in charge of this course for more than forty years, for which she always brings new figures every week. “I learned step by step, and then I was able to make my own creations, like my husband. We make basic origami and sunny origami, which is made with circular paper,” explains Angélica.

For her, an advantage of origami is that by learning the basic folds, for which she relies on some very didactic sheets, one can continue practicing on one's own and learning new designs using Internet videos. “I'm only in charge of giving them the first impulse,” says the teacher whose son, the publicist Ezequiel Sánchez Molina, also makes origami and uses them in his professional work.

New ways

There are various associations that have been formed to share the art of origami in Peru, mainly in Lima, Arequipa, Chiclayo, Puno and Cusco, and the interesting thing is that it allows different audiences to be incorporated. Marta Silva says that, in addition to children and young people, many older adults are interested in this craft, doing work to give as gifts to their children or grandchildren, to whom they give it emotional value. “Doing something artistic contributes to their self-esteem,” he points out.

The Peruvian Origami Association, Origami Cusco (which held a convention with international guests such as Beth Johnson, Isa Klein and Sergio Guarachi, among others) and Tinkuy Origami are part of this movement that is shared in workshops such as those of the Escuela de Arte Libre and virtual groups such as “Paper of paper”, where they also practice recycling; projects in which Bryan Meza participates, who replicates them in various educational institutions, reinforcing the psychomotor skills of children, young people and adults.

Others have taken origami along entrepreneurial paths, such as the Argentine Paz Flores, who lives in Lima but created the brand “ Paz & Papel ” when she was in Buenos Aires. “We met with a group of friends to make origami, I learned from a young age and never lost my love for transforming paper. I worked in a travel agency and on my desk I had my mini collection of figures. I wanted my life to change direction, to dedicate myself to something that I was passionate about, that was a challenge,” he says.

This is how he merged origami with jewelry accessories. First there were some cranes that are bathed in varnish so that the water does not affect them, with which they arrived in Ecuador and Peru, and then other pieces, packaging and decorations arrived. In Lima, they set up an outpatient stand with their earrings and thus met many people interested in their work, including jewelers who offered them help. “I was always fascinated by how from a square of paper, through a couple of folds, you can make a bird, a ship, an elephant or a dragon.”

The art of the fold

There are those who have made origami a work of art.Gonzalo Benavente studied at the School of Fine Arts and when he was little a family friend brought him a paper robot that, when folded, became a spaceship. “It seemed amazing to me that from something as basic as paper you can generate these types of mechanisms and, above all, be able to play with it.” His father was an architect and his workshop was the first place to experience origami.

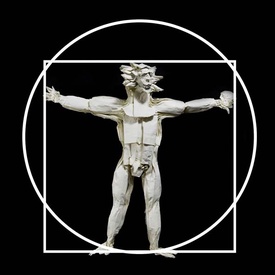

“I entered Fine Arts with an artistic proposal that ended in characters made in origami. In the process it matured, mixing with other arts that eventually followed this direction, but in a way where the fold is no longer so noticeable, but it remains the essential basis of my entire research project,” he adds. As a sculptor, origami is a means to explain the concept of volume, and today much of his work focuses on the creation and study of the fold as an artistic proposal.

Hence “Proyecto Huaco” was born, his latest proposal, which is based on the use of paper and folding with the purpose of promoting the heritage of museums. “I have held several workshops promoting origami in different institutions as teaching material and in 2008 I had an individual exhibition at the Peruvian Japanese Association with around 50 foldings, and I have been invited to participate last year in the Cusco origami convention, as well as of jury in the Tinkuy organization.”

The Nikkei and origami

Many Nikkei say that origami entered their home since they were children. Megumi Nagayoshi says that for as long as she can remember, there have always been origami books at home. “It was part of our life that one day you would take the book and start making a figure. In my family we are three sisters and I am the youngest, I was the one who had the most difficulty making a figure, sometimes I stayed halfway. Later at my school there was also an origami course.”

She started working as an origami teacher at the Peruvian Japanese Cultural Center at the age of 17 and has been dedicated to this profession for eight years, which she has combined with theater. “In 2017 I worked on an origami show, which was telling a story while doing origami live. I appeared at the Ricardo Palma book fair and in a bookstore. In 2018 I participated as an origami artist in an improvisation work called “Zodiaco Soundpainting”, in which I made origami live.” That year he also launched his own brand, Origumi , through which he sells some of his work.

2018 was a very football year in Peru, since the world championship meant the return of the national team to this competition after 36 years. For the artist Diego Teruya it was a perfect opportunity to link his passion for football and origami in the Footb.Art project, for which he has made t-shirts of all the national teams, and of several teams in the world, in origami. “I am a collector and very passionate about football, so the idea of uniting the two was born.”

At first, he thought of making the t-shirts out of cigarette boxes, as was customary before, but then he opted for origami. “It is an art that we have practiced since we were children although we do not realize it. From the child who makes a paper airplane at school to the most experts who are able to build models of cities and landscapes only with paper," says Diego, who lived as a child in Japan, where he marveled at animes, toys and the merchandising they produce. “Without a doubt, it was a great impact for a child who was always interested in art,” he says.

paper culture

Whether they are Nikkei or not, many origami followers feel that through this art they have been able to get closer to Japanese culture. “At first I was not very aware of it, but as I dedicated myself more to this project, I realized that its origin was in everything I had experienced since I was very little. I think that I express my Nikkei identity in some way or another in all the projects I do, whether through illustrations, designs or photography,” says Diego Teruya.

For Megumi Nagayoshi it has helped her “have more interest in my origins. That is, learning more about origami and little by little investigating more about the history, my past and that of the immigrants who came to Peru. I feel that origami helps me spread part of Japanese culture to those around me and also helps me research and want to create new things with Peruvian culture,” he adds.

“Japanese culture is based on discipline, harmony, and patience, that is what we have found with origami. Thanks to this art we have known the message of peace behind the cranes or tsurus, the cherry blossom or sakura, the koi fish and its legend, among others,” says Paz Flores. “In Peru there is interest in the development of origami but only by small groups that promote this art in fairs and exhibitions, it is difficult for it not to be appreciated, but it has not yet been integrated into society in all its versatility,” adds Gonzalo Benavente.

© 2019 Javier García Wong-Kit